Welcome to the first of a new feature on BikePortland: a brief look at the life or work of an extraordinary local person.

When Jim Howell was 37, he organized the first demonstrations that eventually turned Harbor Drive into Waterfront Park. At 40, working as an independent architect, he drew up the design for Northeast Portland’s Woodlawn Park. At 41, he sat on the citizens’ committee that recommended Portland’s first MAX line. At 48, while working for TriMet, he engineered the west-side bus node now known as Beaverton Transit Center. At 51, he co-founded a private van service between Portland and the Oregon coast, a predecessor to today’s Wave bus. At 77, he co-created the plan that became the most prominent alternative to the Columbia River Crossing.

Now, two months before his 80th birthday, Howell has designed his first transportation concept that puts bikes front and center.

It’s a double-decker rail/bike corridor that would, Howell says, dramatically improve transportation through Portland’s central east side while literally creating a car-free second-story commercial district out of thin air.

And as usual, he’s got the renderings to explain it, handbuilt in PowerPoint on his Windows Vista laptop.

“Are you familiar with the High Line in New York?” Howell asks in his soft, thin voice. “We could call this our own High Line.”

“The idea here is to combine light rail and an express bikeway… My off-the-cuff guess is that you’re looking at a $200 million project, which is roughly half what they want to spend to add another damn lane to the freeway.”

— Jim Howell

In an interview Thursday in the kitchen of the Beaumont house he bought for $8,000 after returning from Army service in postwar Germany, Howell sipped Hefeweizen and explained the details of his latest audacious plan.

“I call it ISE-BREW,” he said. He chuckled. “Inner SouthEast Bike-Rail ExpressWay, you see?”

It’s a play on ISTEA, the 1991 federal transportation bill.

Howell likes acronyms. A lot. In 1971, he coined one that stuck: Sensible Transportation Options for People, the group Ron Buel formed with him, Betty Merten and a few friends. Over the next five years, they stopped the proposed Mount Hood Freeway from bulldozing Division Street.

Howell’s new concept isn’t so different: instead of widening Interstate 5 through the Rose Quarter for $400 million, it’d find cheaper ways to move people quickly through the area.

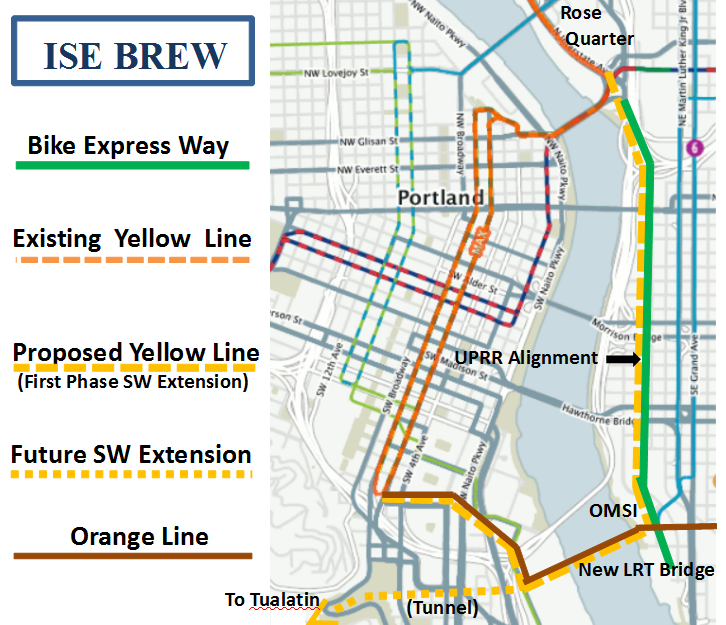

“The idea here is to combine light rail and an express bikeway,” Howell said. “From the Springwater Corridor, it’ll take you directly, fast, right up to the Rose Quarter.”

The most interesting trick: for 12 blocks, from Stark to Clay streets, Howell’s light rail line and bikeway would run directly above the Union Pacific Railroad tracks.

“These are just conceptual – nothing engineering about them,” Howell said as he flipped through the glossy renderings he’s prepared. “But I know they can be done.”

A few years ago, when TriMet was making plans for its Orange Line, Howell conspired with a friend at TriMet to survey whether a raised platform like this could thread through the Rose Quarter’s bramble of overpasses. It could.

At its north end, the bikeway and light rail line would connect directly to Wheeler Avenue, then run between Interstate 5 and the railroad line until just north of the Burnside Bridge:

At the rapidly developing Burnside Bridgehead, ramps and maybe elevators would connect the bikeway and a new Burnside Street MAX stop to the bridge and bus lines above:

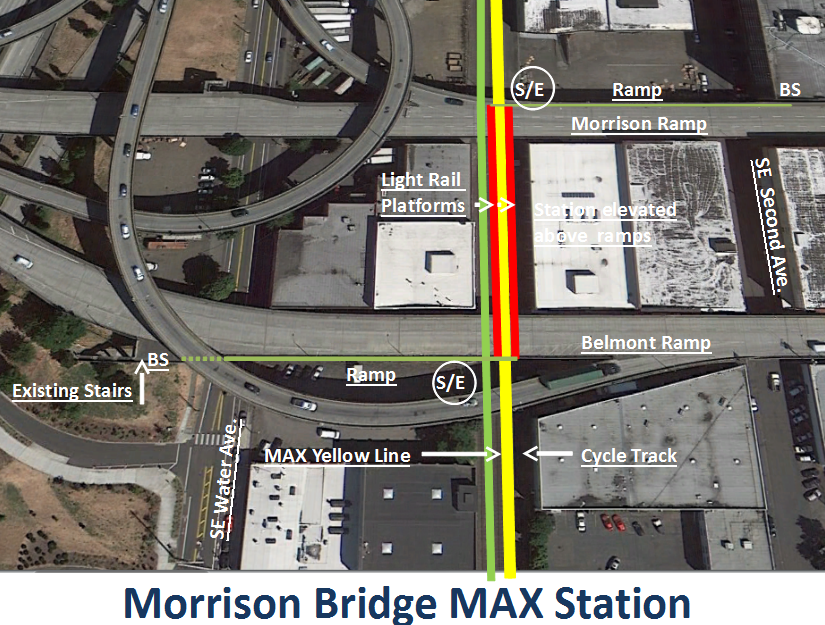

South of the Burnside, the bike path and light rail would climb at a 3 percent grade to above the Morrison and Belmont viaducts, then descend again to the level of the Hawthorne-Madison viaducts and finally connect to the new Orange Line light rail bridge.

The adjoining buildings, Howell said, would then be able to open storefronts that open onto the new bike-rail path and the bridges themselves.

The result would be a connected loop of criscrossing rail, bus and bikeways that Howell says could move at least 2,000 people an hour — about as many as a freeway lane can carry.

“My off-the-cuff guess is that you’re looking at a $200 million project, which is roughly half what they want to spend to add another damn lane to the freeway,” Howell said. “It will reduce the traffic demand on I-5, MLK and Grand and it would provide a true north-south, traffic-free cycle track. And it would also provide a north-south rapid transit line from Vancouver south to Tualatin, which is sorely needed because there is no south leg to that. And it provides far better connections between MAX and buses. The heaviest ridership in the system is on the east side.”

I asked Howell how this would be different from the nearby Eastbank Esplanade, along the river.

“Its purpose is not recreation, just like the purpose of the freeway is not recreation — this is a bicycle freeway,” he said. “The Esplanade suffers from its popularity. It’s such a great thing that there are so many people using it in their wheelchairs, their strollers, their kids. Think back in the 60s when we started putting freeways in because roadways got clogged up. You might say this is kind of a parallel situation. It becomes so popular that we need an alternative.”

Howell said he hasn’t been able to ride a bike himself for 40 years, when he developed chest pains during a long ride and wound up in bypass surgery. Today he gets around by transit, car and foot. He moves with a stoop, his shoulders pushed forward by years of leaning over sketches, keyboards and committee tables.

Howell said he spends maybe 10 hours a week on his transportation advocacy. It’s been volunteer-only since he left his TriMet job in 1985, sick of working inside a bureaucracy. His only official title these days, which he can’t remember without looking at his business card, is “director, strategic planning” for AORTA, a volunteer citizens’ rail and transit advocacy group.

“My wife thinks I’m crazy, and my kids,” he said.

It hasn’t stopped him.

“There’s always a project,” Howell said quietly, finishing his beer. “You can’t be too impatient, because it takes 10 years to get anything done. That’s been my theory, anyway.”

Corrections 11/25: An earlier version of this post inaccurately described the line’s proposed crossing of the Morrison Bridge and the quadrant of Woodlawn Park.