The Hayhurst Neighborhood Association (HNA) has decided not to appeal the Hearings Officer’s November 8th decision to approve the Land Use permit for the proposed 263-dwelling subdivision of the Alpenrose Dairy site. After an emergency board meeting, held on November 20th, a little over a week after the group had voted to appeal the HO decision, the HNA decided ultimately not to file an appeal. No group or individual met the November 22nd appeal deadline, which means that the HO’s decision stands, and the Raleigh Crest development can move forward with its plans.

The HNA issued a press release early Friday evening which stated that they had, hours earlier, signed an agreement with Walter Remmers, an owner of Raleigh Crest LLC. The agreement covers, 1) monitoring the environmentally sensitive wildlife crossing at the southern end of the property and 2), funding a traffic study “to help support future safety improvements to SW Shattuck Road and its intersections, particularly the SW Illinois/60th intersection at the entrance to the new development.”

I spoke with HNA Chair Marita Ingalsbe Friday evening and she added some details to the press release.

Concerning the traffic study, the developer has agreed to fund up to $50,000 for the study, the scope and date to be determined by the HNA. This flexibility means that HNA could obtain real-world traffic information after the first phase of the development is built. The thinking is that real data, collected after a partial build-out of the housing, and years after any pandemic-related traffic depression, would better inform road safety improvements than the Trip Generation tables traffic engineers use for estimates.

Analysis

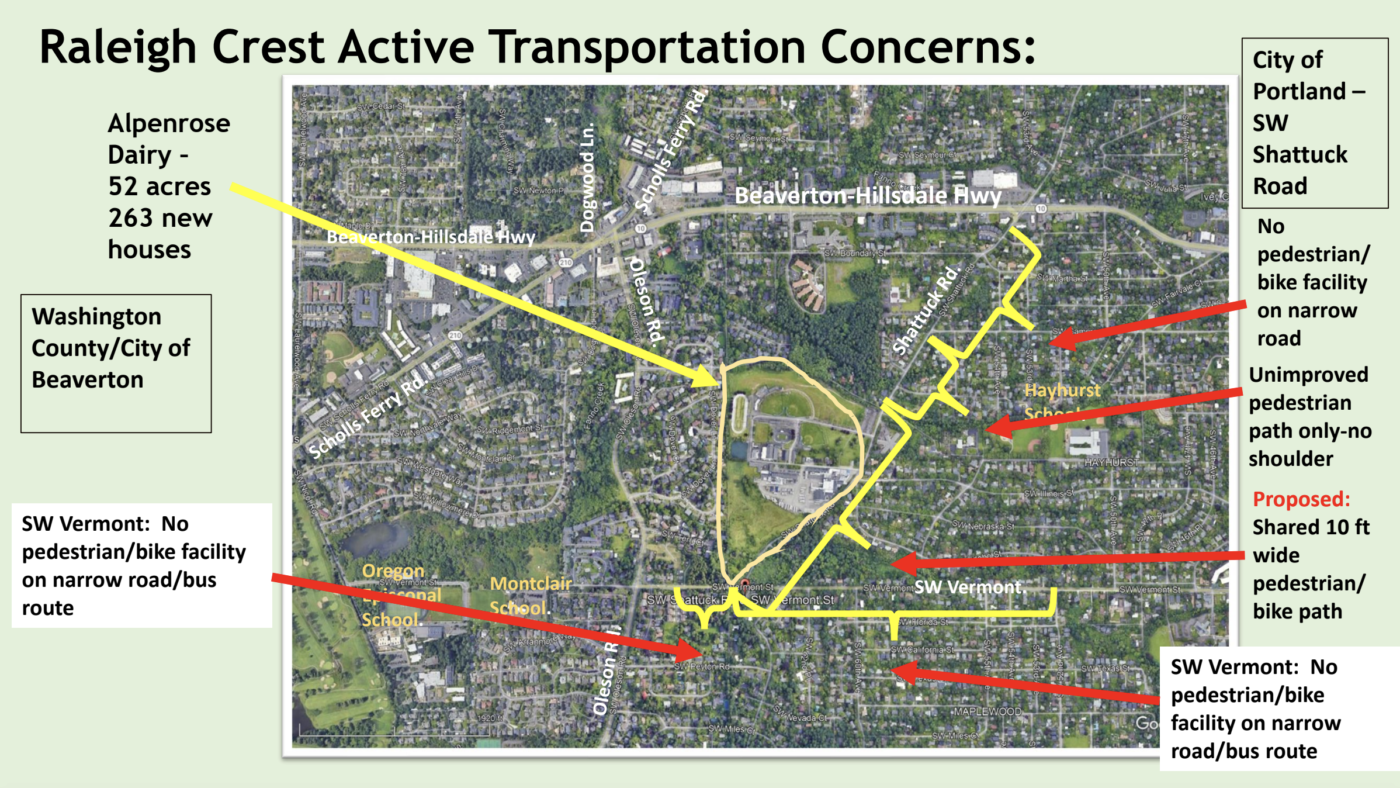

At first glance, it might seem that by backing off the appeal the NA has given up its leverage for obtaining safety improvements. Of particular issue has been the intersection of Shattuck Rd, Illinois St and 60th Ave, which sits at the entrance to the new development to the west, and to a Neighborhood Greenway and Safe Route to School to the east. The intersection would be the main route for elementary school children from the development to reach their school, Hayhurst Elementary, two blocks away.

The HO approved the Land Use (LU) permit without the stop signs or speed bumps that the developer’s traffic consultant had initially recommended for traffic calming.

It’s a gambit, but one possibly significant consequence of not holding up the LU permit is that it removes authority over the street design from the Public Infrastructure section of Portland Permitting and Development (PP&D) and puts it back in the domain of the Portland Bureau of Transportation (PBOT).

The pathway for transportation spending differs between capital projects (public money) and private development (developer money). Portlanders are mainly familiar with big capital projects, things like the “in Motion” plans and the 102nd Avenue Safety Corridor project. Those projects are designed by PBOT planners and funded with taxpayer money. They invite public input, and process and public outreach are a big part of the efforts

That is a world apart from the traffic mitigations and frontage improvements the city requires of developers. Most important, the group which oversees them is different. PP&D Transportation Development Review has a different design culture, and they are independent of the non-binding transportation policies the City of Portland has adopted — things like Vision Zero, Safe Routes to School, 15-minute neighborhoods and PedPDX.

Unlike PBOT, PP&D makes decisions with one eye on Nollan/Dolan jurisprudence (the developer appeals the decision) and the other eye on the Neighborhood Association, which can also appeal. A successful outcome for them is no appeals, and then the group moves on to the next project. They work under a lot of pressure to keep development moving forward and on schedule, and their right-of-way requirements are often minimal.

The region is like a puzzle with half the pieces missing, a disconnected network built piecemeal, development by development.

I don’t have the data to back this up, but I would say that most of southwest Portland’s right-of-way design is the product of the developer-funded pathway. That is probably why the southwest has, by far, the least sidewalk coverage and most disconnected bike network of any area in the city. The region is like a puzzle with half the pieces missing, a disconnected network built piecemeal, development by development.

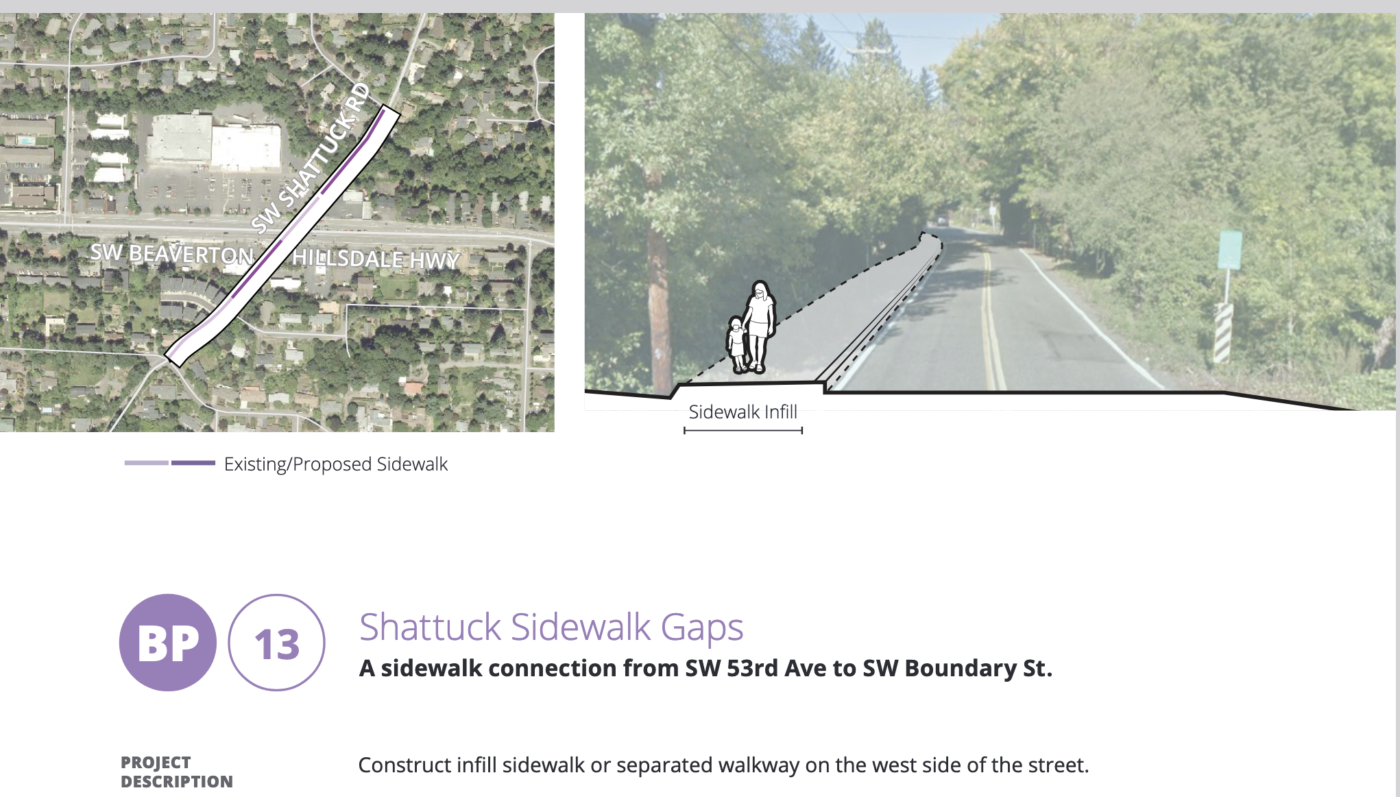

So putting Shattuck safety improvements in the hands of PBOT might have some advantages. From an advocate’s point of view, it opens up the discussion to other parties. Whether because of custom, courtesy or city code, transportation advocates defer to the NA in Land Use cases. That can shift once road improvements move out of the development realm. For example, there are a couple Southwest in Motion (SWIM) projects on Shattuck, and SWTrails has an interest in Shattuck because its Red Electric Trail crosses the road.

The change in authority means that the city will have to pay for any safety improvements, not the developer. But at stake in this disagreement were speed bumps and stop signs — not big-ticket items. And the most important safety improvement to the road — continuing pedestrian and bike facilities all the way to Beaverton-Hillsdale Highway — was never on the table with the developer. The city can’t expect a private land owner to foot the bill for decades of its infrastructure neglect, and Nollan/Dolan jurisprudence ensures that.

Another change which could work in favor of active transportation in southwest Portland is the new system of district representation. Many District 4 candidates made a point of following Shattuck and the Alpenrose development — more accountable representation and less politicized bureaus might shift how and where PBOT spends money.

If all goes well, Raleigh Crest could break ground in the summer of 2026. And my prediction is that our new City Council and Mayor will be focused on homelessness for their first year. So I don’t expect much more transportation news regarding SW Shattuck Road for a while.