I read a lot of BikePortland comments. Actually, I read all the comments, even the ones that Jonathan approves before I get to them. About 30,000 comments last year. (Yes, it probably does do something to your brain.)

The caliber of your comments is impressive. Sometimes a news post seems merely like a cue for the knowledgeable discussion that follows it.

Every so often, though, I push a comment through that I’m pretty sure is incorrect. We don’t have time to fact check comments, but sometimes curiosity gets the better of me and I might quickly try to find out, say, which neighborhood is really the most dense in the city (the Pearl), or to verify which neighborhood coalition represents the largest percentage of the city’s population (a tie between Southeast Uplift Neighborhood Program and East Portland Community Office at around 26% each).

Some of that simple factual information, “which is the fastest growing neighborhood in Portland?” can be surprisingly difficult to find.

That’s why I was excited to hear Michael Montoya, the interim director of Portland’s Office of Community and Civic Life, speak to my neighborhood association last week. His topic was Civic Life’s Portland Engagement Project (PEP).

This year the PEP will release an information-rich, interactive map of neighborhood profiles made in collaboration with the Portland State University (PSU) Population Research Center.

Data from a number of sources will be aggregated: the 2020 census; the American Community Survey; Feeding America food insecurity data; CDC Social Vulnerability Index; the book Portlandness: A Cultural Atlas; and National Center for Health Statistics Life Expectancy Estimates.

This will be an invaluable resource for city employees, advocates, the public—anyone who values accuracy, even BikePortland commenters. The great thing is that all this information will be in one place—demographics for every neighborhood will be a click away. (And technocrats will appreciate the work that went into adjusting the data to neighborhood boundaries. For example, the federal government reports census data in census blocks, which don’t align with the neighborhoods. It’s a headache which the profiles make go away.)

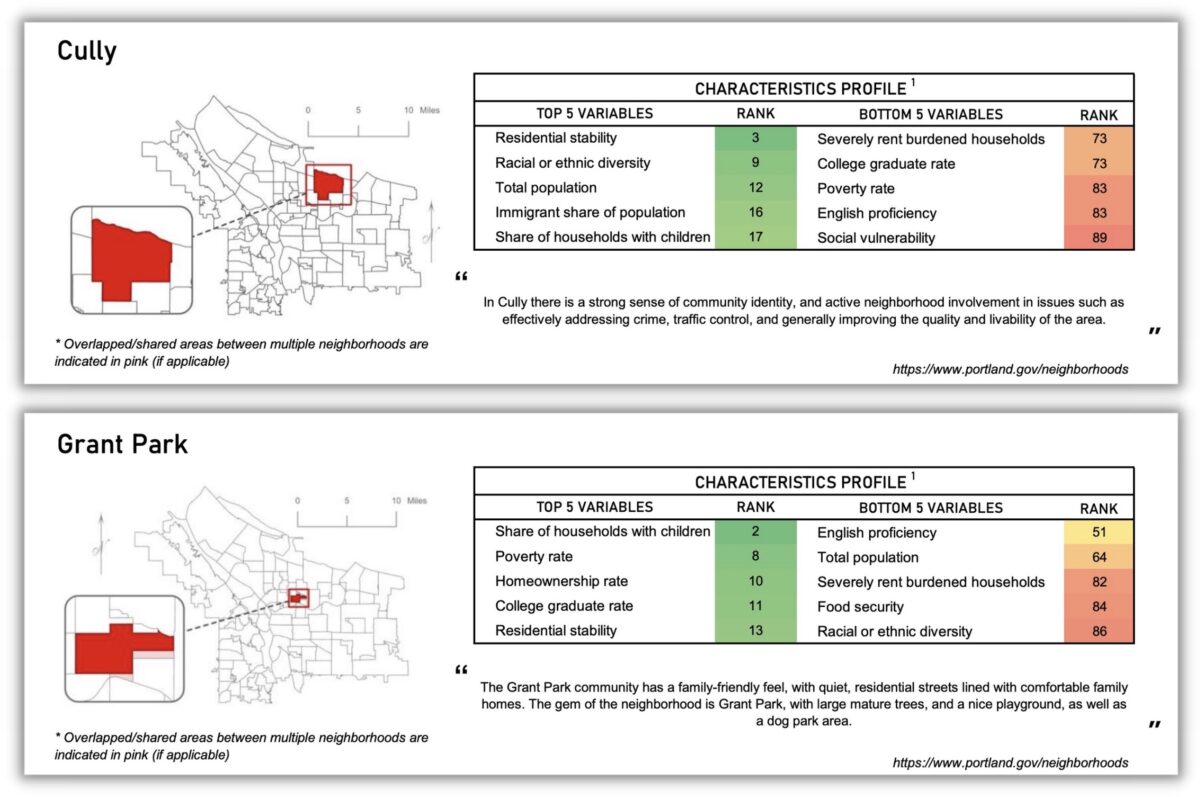

Here is the preliminary profile of Cully. You can see that Cully is one of the most racially and ethnically diverse areas in town, and that 13% of it’s residents are “severely rent burdened.” A quick glance at the Grant Park neighborhood shows that it is one of the wealthiest in the city. What does your neighborhood look like? Check it out in the preliminary profiles of all 94 neighborhoods.

Montoya pointed out that the work on the Portland Engagement Project is being done in the context of “the herculean task” of charter reform, and that there is a “debate happening in the city right now around who should usher in these transitions.” Currently, city engagement with the public is not good, his office is grappling with what future engagement should look like.

Listening to him, it occurred to me that the public-facing charter reform transition is essentially a map reconciliation project.

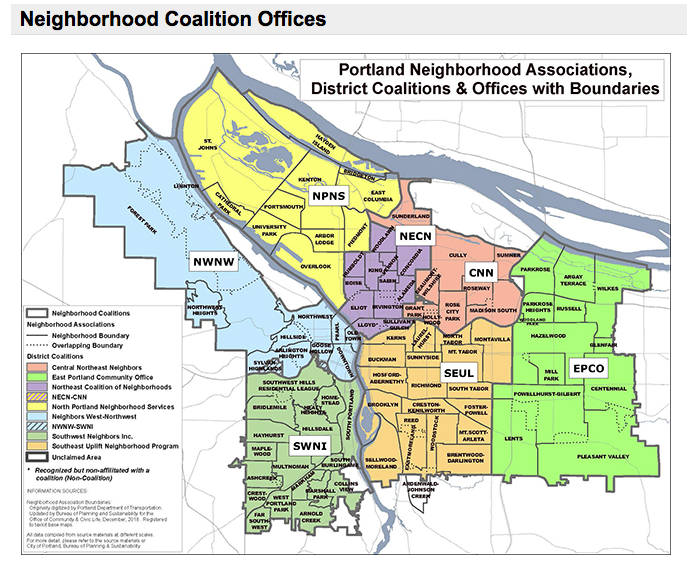

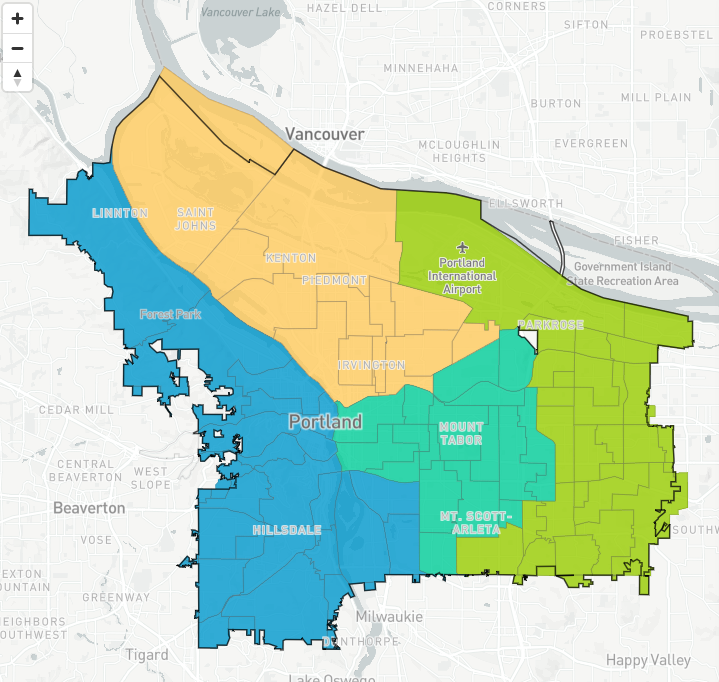

Portland groups its neighborhoods into seven coalitions. How will those seven neighborhood coalitions map onto charter reform’s four council districts? Will neighborhood coalitions be retired, with district offices absorbing the support work they provide for NAs?

For example, the charter transition will need to reconcile the neighborhood association (NA) structure with the new district structure. Portland groups its neighborhoods into seven coalitions. How will those seven neighborhood coalitions map onto charter reform’s four council districts? Will neighborhood coalitions be retired, with district offices absorbing the support work they provide for NAs?

This might not sound like anything but paper shuffling to those unfamiliar with the central role of NAs in the city’s engagement process, but it really is transformational. In a city without district representation, where each commissioner has been elected “at large” by the entire city for over 100 years, the neighborhood association structure was created to provide “channels of communication” between City officials and “the people of Portland.” At large voting and the neighborhood association structure have worked symbiotically for almost 50 years, they go hand and hand.

Montoya talked about the history of Portland’s NA framework. It came about at the end of the Vietnam War, and just after Watergate:

. . . the distrust was maybe even higher than it is now. Forming neighborhood-based associations was a way to influence and provide some check and balances on governments that were completely non-responsive.

But over the past few years NA primacy has been challenged—by former Commissioner Chloe Eudaly, by the director she appointed to the Office of Civic Life, Suk Rhee, and by culturally-specific organizations which would like a comparable seat at the table.

It has even been questioned by BikePortland readers, remember the Fremont and Alameda diverter controversy? There sure was a lot of confusion about what power a neighborhood association holds.

The reality is, today’s neighborhood association are mainly able to influence projects through their role as information conduit between neighborhoods and bureaus. They can pass on concerns and suggestions which PBOT will take into consideration. And that’s it. Fremont at Alameda now has its bike-friendly greenway protecting diverter, despite the initial neighborhood vote.

Portland and the country once again find themselves in an era characterized by mistrust of government and complaints about lack of representation. Our solution this time around has been to change how we vote and the way we are represented. What is still to be seen is what the working relationship between district city council offices, neighborhood associations and city bureaus will look like.

The Portland Engagement Project wants to hear from you and will be begin community listening sessions early this year. In the spring the City and PSU will host a summit to discuss public engagement practices, and in mid-2023 the City will host informational meetings to share the neighborhood profiles. Stay tuned. We need to make sure our voices are heard in the next era of civic engagement in Portland.