— Taylor Griggs contributed to this story.

If you use Portland’s streets, you know there’s room for improvement. From crumbling and cracked pavement on greenways, to debris-strewn bike lanes and cavernous potholes — basic street upkeep has fallen by the wayside.

There’s a number behind all of Portland’s unmet maintenance needs: $4.4 billion.

If you’ve spent any time doing transportation advocacy in this town, that number is likely very familiar to you. This statistic is often used by Portland Bureau of Transportation leadership and staff as an excuse to do nothing. One of the most effective ways to shut down requests from people who want a new project or program to be funded is for someone to say, “We’d love to, but we have a four billion dollar maintenance backlog to worry about.”

PBOT Commissioner Jo Ann Hardesty does this all the time. She recently cited the backlog as a reason the bureau has struggled to placate disgruntled maintenance workers. She also mentioned the backlog several times in our podcast interview last year, expressing that it’s one of the main things dragging down PBOT’s potential.

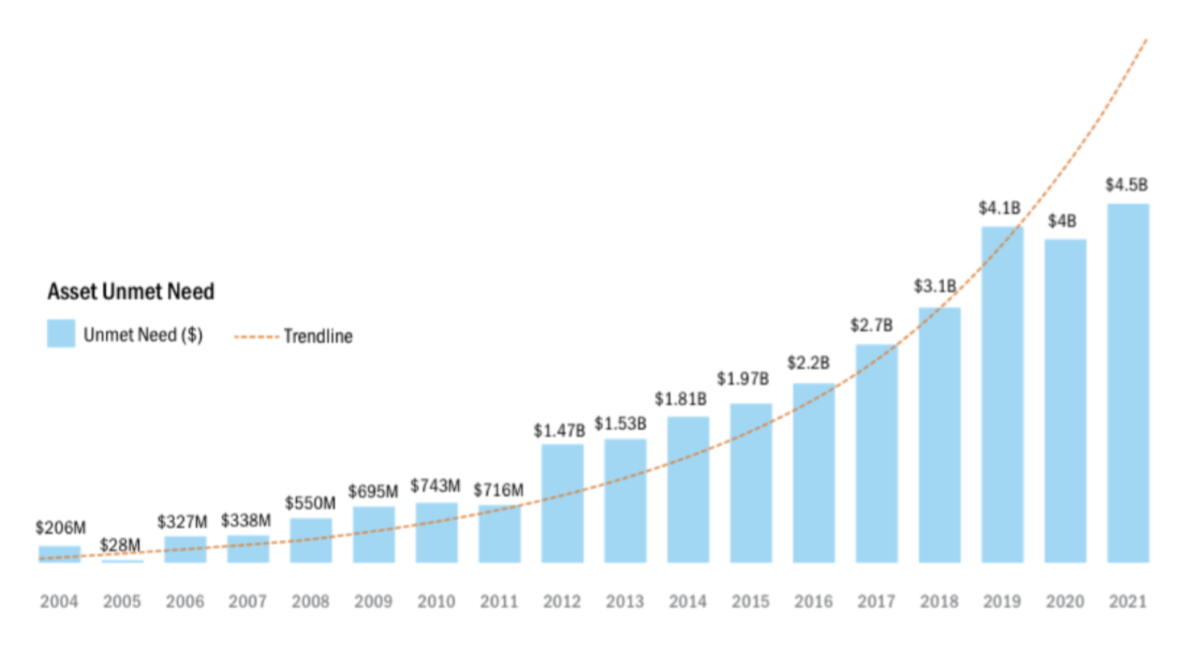

But the maintenance backlog didn’t start with Hardesty. PBOT commissioners and staff have long lamented about the seemingly interminable problem that keeps growing every year (see above).

“Continuing to maintain the assets…particularly the most costly facilities (like arterial pavement and bridges) is challenging for jurisdictions across the country as funding for ongoing repair, rehabilitation, and ultimately replacement were assumed to be covered by the federal gas tax, which was last increased in 1993 and which we know is woefully insufficient to keep up with aging infrastructure,” PBOT Public Information Officer Dylan Rivera shared with us in an email this week.

Politics don’t work in its favor either. Maintenance work is decidedly unsexy and there are no ribbon-cutting events for sweeping a bike lane. As Cathy Tuttle pointed out in a recent BikePortland guest article, maintenance “just doesn’t have the same political oomph that ‘new’ has.”

Another reason our roads are in such poor condition is because our transportation system strongly favors the type of vehicles that damage roads most. There are tens of thousands of extremely heavy cars, buses and trucks rolling over our roads on a daily basis, and as more people buy larger and heavier ones (EV batteries being the main culprit), the problem will only get worse.

The picture looks even more bleak when you realize that federal grant programs — a huge source of funding for capital projects — don’t pay for maintenance. That means PBOT has to use “discretionary” funding for maintenance, a source the agency has been forced to reduce by 9% in the last two budget cycles.

So what, exactly, is on this infamous backlog? And can the city’s current approach even begin to tackle it?

What does the backlog consist of?

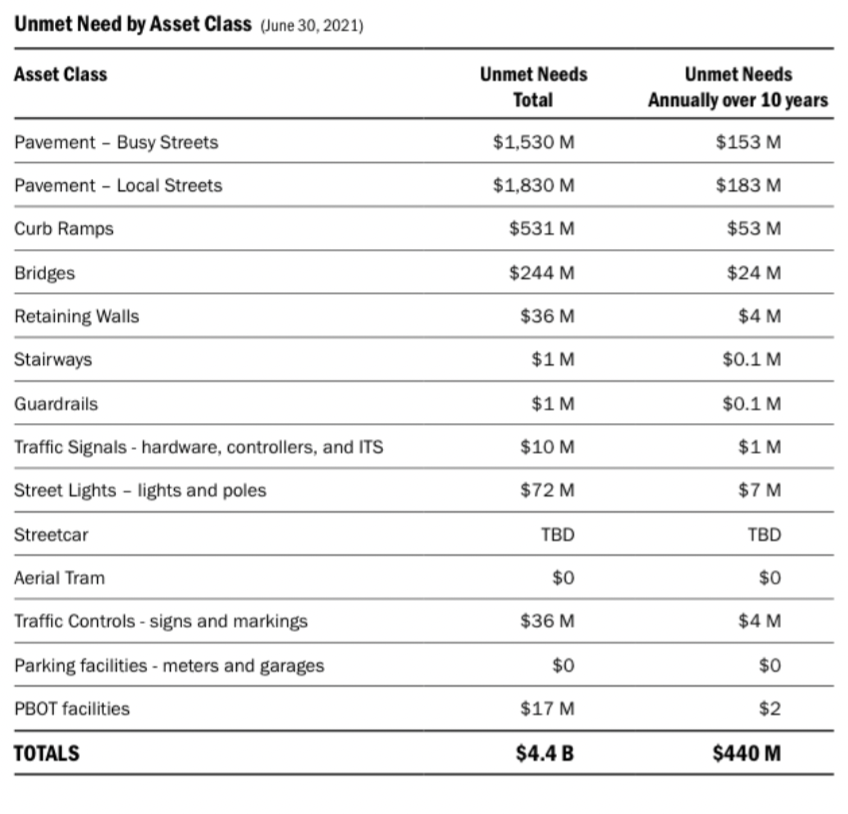

PBOT’s Rivera tells BikePortland the $4.4 billion refers to the bureau’s “unmet need” – the calculation of how much it would cost to bring the bureau’s $18 billion in assets to fair or better condition in 10 years. According to this calculation, it would require the city to dedicate $440 million a year to maintenance for 10 years to get assets into that level of condition.

Taking up the bulk of this cost is unmet road maintenance needs. This includes $1.5 billion for busy streets and $1.8 billion for residential streets in various states of disrepair. A Citywide Assets Report released in 2019 deemed the majority of Portland’s arterials and local streets in ‘poor’ or ‘very poor’ condition. Other big contributors to the backlog include streetlights, curb ramps and bridges.

Not figured into these totals are the millions PBOT is forced to spend every year due to infrastructure damaged by incompetent and/or reckless drivers who plow over signs into poles with alarming regularity.

A 2013 city report detailing the condition of Portland’s pavement said it would cost about $750 million over ten years to get roads in proper condition. In 2015, the backlog totaled $1.2 billion, increasing to more than $2 billion by 2017. A little more than five years later, we’ve doubled that price. This proves a dire warning we often hear from PBOT staff: the longer we wait to fix roads, the more expensive it gets.

Potential solutions

The people running Portland’s transportation system have championed a variety of efforts to pay for maintenance over the years. Way back in 2007, former mayor Sam Adams pushed a “Safe, Sound and Green Streets” fee initiative for Portland households that would have raised money for maintenance work (back when the deficit was still manageable). After that initiative died, former PBOT Commissioner Steve Novick advocated for a similar program in 2013 – a universal “street fee” – which also never came to fruition.

Finally, in 2016, Portland voters approved the Fixing Our Streets program as a way to fund street maintenance projects using a $0.10 per gallon fuel tax and a Heavy Vehicle Use Tax. Policymakers knew this program wouldn’t be able to solve every problem in the city, but it was a start. And like many PBOT funding sources, it has a double-pronged approach. Not only is the tax a source of revenue, but the hope is that increased fuel prices will incentivize people to drive less so less pricey maintenance work would be required in the long-term.

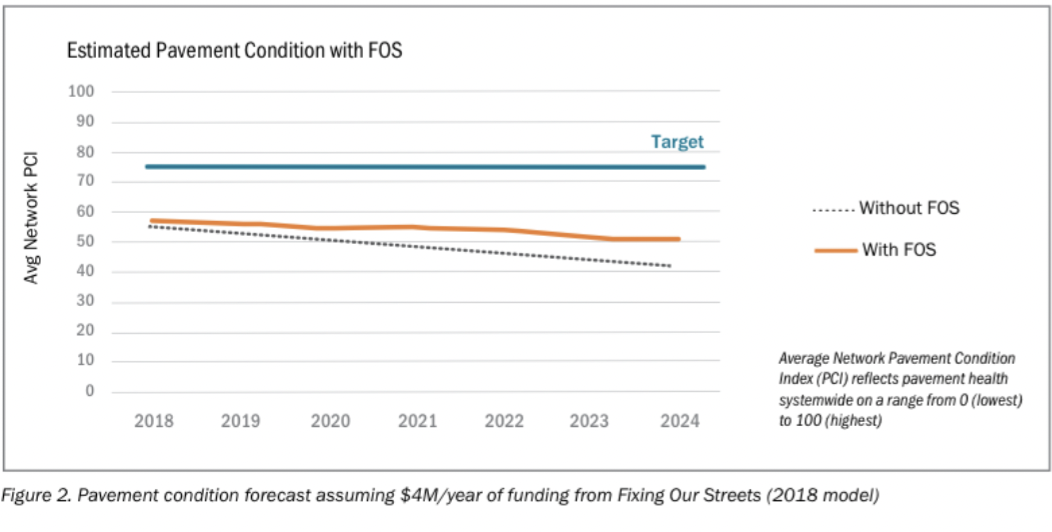

The backlog has only grown since the passage of Fixing Our Streets. Even so, PBOT says the money has been put to good use to stave off some of the worst outcomes (see chart at right).

“The Fixing Our Streets program has made a big difference in preserving and extending the life of the city’s pavement, in addition to providing some critical safety improvements,” Rivera said. “No one ever said FOS alone would be enough to solve the maintenance backlog that took a half century to produce.”

So, in a scenario in which everyone either rides a bike or drives an electric vehicle (a utopia for many advocates), the FOS money would run dry fast. That’s where the city’s Pricing Options for Equitable Mobility (POEM) effort comes in. Or, was supposed to come in. Launched in 2019 and adopted by City Council in 2021, the POEM Task Force outlined several ways PBOT could raise revenue. Unfortunately, the recommendations of the task force have yet to move forward.

One new fee PBOT has begun to collect (which wasn’t technically part of POEM) is a new parking fee that was created out of desperation following a massive decline in drivers filling meters during the pandemic. But that fee is estimated to collect just $2 million, a drop in the bucket.

What now?

The backlog is as bad as it’s ever been. We have less money than ever. And the morale at PBOT’s Maintenance Operations division is at its nadir.

It feels like PBOT and City Hall’s courage to implement the new revenue ideas from the POEM plan is diluted by their fear of losing out on the car-based, cash cow, status quo. But the sooner we rip off the band-aid, the sooner we can heal our streets and our budget.

In the short-term, we must get PBOT’s Maintenance Operations group on better footing. This has nothing to do with a lack of funding and it goes beyond looming threats of a strike. We’ve recently heard about a lack of trust between staff and leadership, a dysfunctional institutional culture, and eye-popping staff turnover rates. This constant reshuffling of staff is very disruptive to work crews and their programs, and leads to less work getting done. Our fingers are crossed that new Maintenance Operations Director Jody Yates, who was hired in February, can right the ship.

We also must charge people more to use our streets. With inflation and income inequality at all-time highs, and with transportation not even being on the political radar in Portland these days, that will be a tough pill to swallow.

To make it easier to swallow, we should consider a different the narrative around the issue. Our goal shouldn’t be to raise more money to do more maintenance; the goal should be to do less maintenance. The situation is unsustainable not because we lack funding, but because we are living above our means. We spend too much money fixing damage from vehicles that we can’t afford to support any longer, and we don’t do enough to make things we can support — like biking, walking, and taking transit — viable options.

Portland has a long legacy of supporting carfree spaces. Former Mayor Vera Katz declared September 14, 2004 as “Portland Car-free Day.” In 2008 we hosted the international Towards Carfree Cities Conference. And even the recent POEM initiative had, “Our system today over-prioritizes cars” as one of its foundational principles. But despite years of rhetoric and advocacy we still haven’t fully embraced the idea of permanent carfree streets, despite the fact that every time we dip our toe in the water — with programs like Sunday Parkways or recent plaza and public safety projects — it feels good.

We need more attention on the problems we face today and the political will to do things differently tomorrow. The maintenance backlog excuse should not be the end of the conversation — it should be the start of a new one.