“Concern for making Hawthorne ‘people-focused’, not ‘machine-focused’ was expressed.”

— Notes from February 1996 Hawthorne Transportation Plan meeting

We’ve been here before.

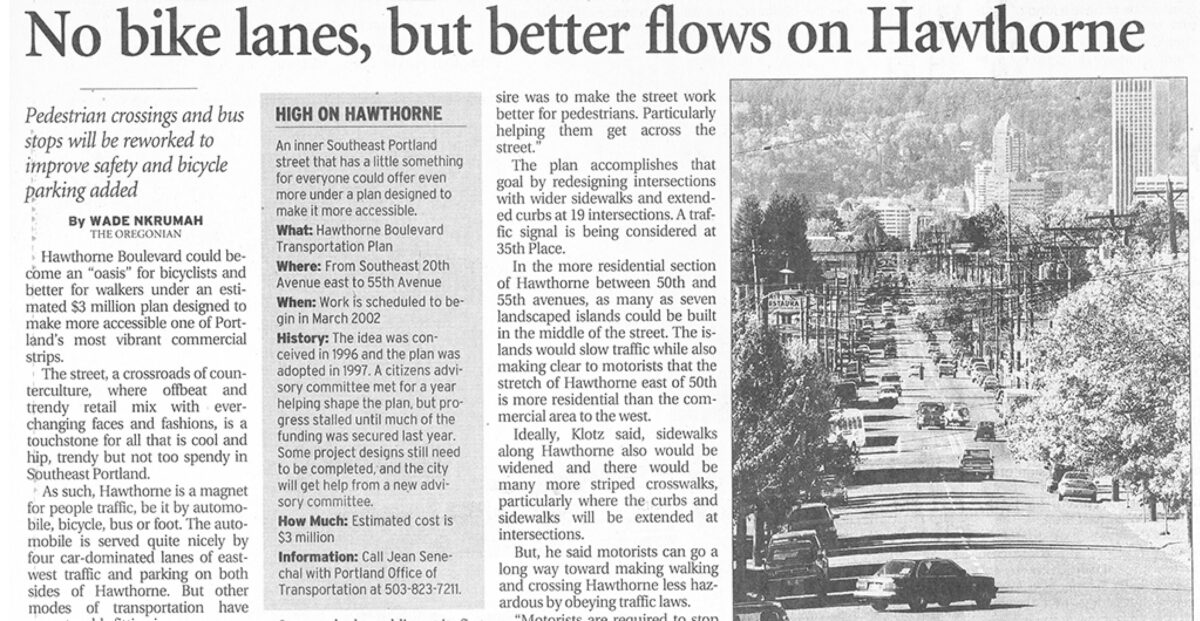

As we await a decision from the Portland Bureau of Transportation about whether or not they’ll to restripe a dense commercial section of Southeast Hawthorne Boulevard with bike lanes, I thought it’d be fun to rewind the clocks a bit.

I briefly mentioned the Hawthorne Transportation Plan back in April, but it merits more attention. I’ve since heard from people who sat on the plan’s citizen advisory committee and have tracked down official meeting minutes.

Let’s close our eyes and go back a quarter century…

Advertisement

Portland bicycle commute mode share (according to the U.S. Census) in 1996 was just under 2%. Even so, it was a 23% jump from the year before and Portland was seen as a beacon of bike-friendliness in America, earning “Most Bicycle Friendly City” honors from Bicycling Magazine in 1995. That same year we adopted the most comprehensive and innovative bicycle master plan in the country. A promising politician named Earl Blumenauer had just left Portland City Hall for Capitol Hill and his leadership of the transportation bureau was taken over by Commissioner Charlie Hales, who would go on to become mayor. Our bicycle program was hitting its stride with the inimitable Mia Birk at the helm. With visionary Mayor Vera Katz (whose name now adorns the Eastbank Esplanade) Portland had all the building blocks of a bicycling explosion.

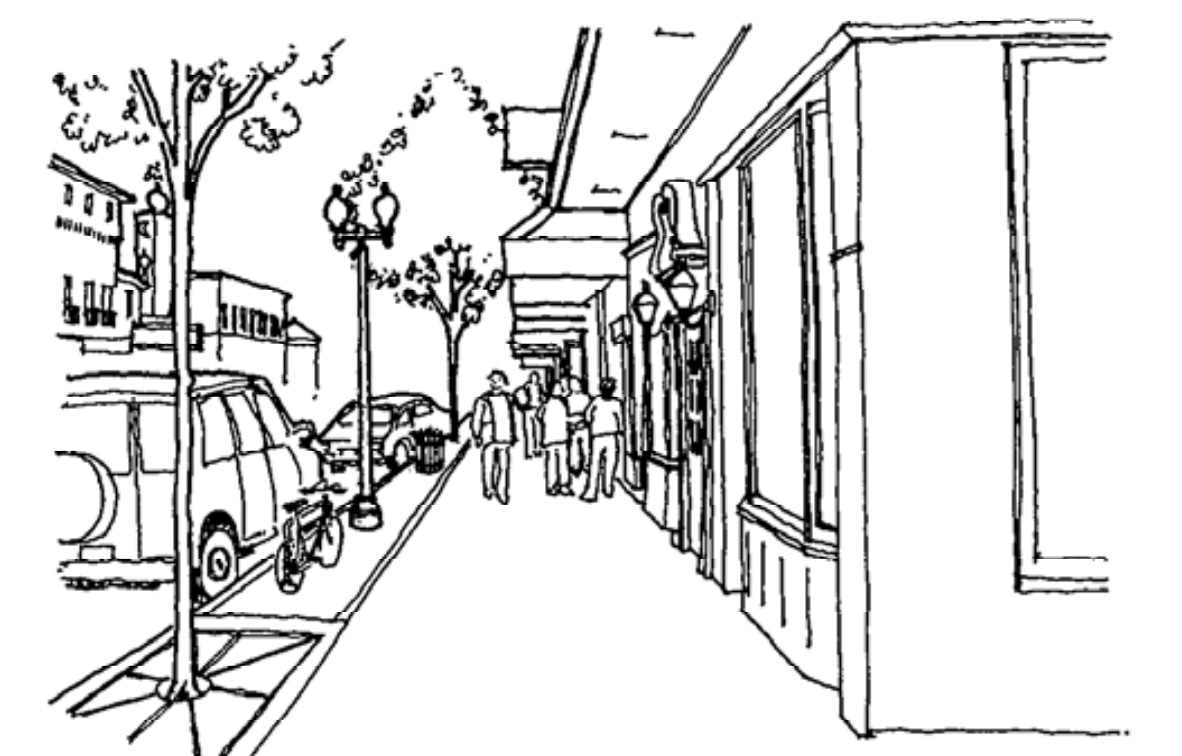

In an article in The Oregonian on September 19th, 1996, PBOT Commissioner Charlie Hales said it was time for main streets in southeast Portland to “return… to their traditional use as multipurpose thoroughfares.” “He said streets like Hawthorne Boulevard and Belmont Street that once had other transportation modes like streetcars have been transformed into streets that primarily cater to automobiles only,” the article reads. “Now we’re trying to correct that imbalance and involve more people,” Hales said.

In 1995, the City of Portland began planning for changes on Hawthorne Boulevard. The commercial area had become a bustling foot traffic magnet and the presence of so many cars and their drivers had made getting across it difficult. “Conflicts are obvious in the battles that pedestrians must wage every day against vehicular traffic as they attempt to cross,” read the introduction to the plan (PDF). Just under the need for safer crossings was another problem: the safety of bicycle riders.

“Bicyclists must compete with cars for the narrow travel lanes,” the plan states. “The planning process sought to produce a greater balance among the users of Hawthorne with an emphasis on alternative modes of travel.”

Advertisement

The city’s Pedestrian Transportation Program brought together an advisory committee to decide on what changes to implement. Advocates, neighborhood association leaders and business owners spent about two years meeting and analyzing options. They focused on four things: “traffic issues, pedestrian issues, parking issue, and bicycle issues.” The number one concern for walkers, say meeting minutes from a February 6th 1996 meeting, was “getting across the street.”

Some of the names on the advisory committee will be familiar to Portland advocates today.

When asked at that February meeting what values should be added to the project, two people spoke up. One of them was Doug Klotz, who helped write Portland’s 1998 Pedestrian Design Guide and was co-founder of the Willamette Pedestrian Coalition, the nonprofit now known as Oregon Walks. Klotz wanted the Hawthorne plan to “express the community’s concern for the environment”. The other person who spoke up was Lenny Anderson, who lived near Hawthorne. Anderson went on to be known as “Mr. Swan Island” for his decades of advocacy on behalf of cycling and transit use in the north Portland industrial area. He said a key value for the project was, “Reducing noise and air pollution and encouraging less polluting access to and through Hawthorne Boulevard.”

Klotz also pushed for the project’s goals to reflect Portland’s goals to reduce automobile use. A “concern for making Hawthorne ‘people-focused’, not ‘machine-focused’ was expressed,” the notes state.

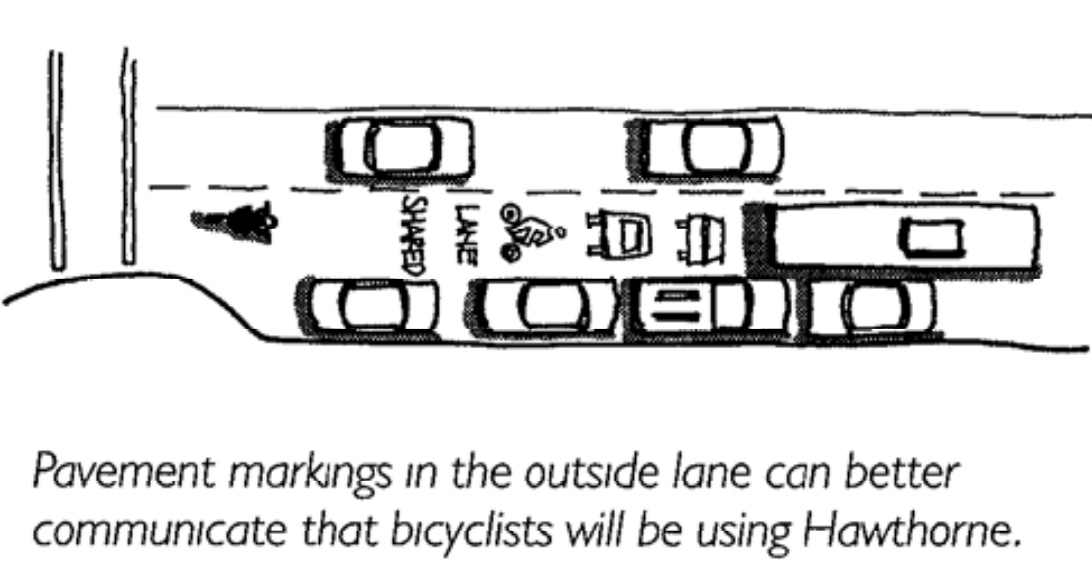

The Bicycle Transportation Alliance (now The Street Trust) was also at the table. They wanted bike lanes badly enough to mount a campaign dubbed “Bikes Work on Hawthorne” that included stickers and illustrations like the one above. Karen Frost, who worked on the campaign said their ideas were ultimately rejected by PBOT staff. “I hope PBOT will be a bit more enlightened this time,” she shared with me in an email yesterday.

While there were strong voices on the committee for changes that would help bicycling and walking, there were others who were not enthused. Neighborhood association rep John Laursen felt like the early tone was too focused on making changes. He and a few others felt the street worked fine as-is and expressed an “If it isn’t broken, don’t fix it,” sentiment (to which Anderson retorted, “It is broken if people can’t get across the street.”)

Advertisement

Five design alternatives were on the table (view details on each of them from this 1996 project document):

Alternative 1 – Non-Physical Alternative

Implement ideas like traffic and code enforcement, minor maintenance or business partnerships.Alternative 2 – Minimum Intervention

Provide pedestrian crossing improvements, slower traffic speeds, bike improvements and more while maintaining the existing four-lane road cross section.Alternative 3 – Select Intervention

Provide improvements for bikes and/or pedestrians by removing one westbound traveling in key locations. (Alternative 3A – Eastbound bike lane, 12th to 30th. Alternative 3B – Wider sidewalks, 17th to 23rd and 34th to 39th, 36th to 50th.)Alternative 4 – Corridor Intervention

Remove one or two travel lanes to provide continuous bike lanes and wider sidewalks in key locations.Alternative 5 – Hawthorne streetcar

Reintroduced a streetcar line to Hawthorne Boulevard. (Note: This option was popular, but wasn’t thoroughly vetted with the others.)

A project survey found a strong majority of people were “not entirely satisfied” with how Hawthorne was functioning. The survey rated the issues at the top of people’s minds: “Bicycle use and safety, parking and traffic” were the top three things most people were dissatisfied with. From a specific list of changes, “Pedestrian crossing improvements” were ranked most important. Parking and traffic were second and third.

As such, the debate centered around alternatives 2 and 3. Most people supported Alternative 2 because it would have some positive impacts on safety and wouldn’t require the same impacts to auto parking, auto congestion, and auto traffic diversion into adjacent neighborhood streets. That being said, there was significant support for the bike lanes in Alternative 3. There was a lot of technical talk about how bike lanes could be implemented in a way that would avoid major auto parking impacts or peak-hour delays for drivers.

One notable comment recorded in the minutes of the final and decisive meeting on January 7th, 1997 came from Randy Albright (yes the same person who sued TriMet for a close pass on the Hawthorne Bridge in 2006). According to the minutes, Albright expressed frustration that group, “saw bikes as ‘the enemy'”. “Randy commented that the bicylists worked to come up with solutions but that the committee was not interested in them.”

Mac Prichard, the Richmond Neighborhood Association rep said he supported Alternative 3B, “as long as it didn’t require parking removal”. “Mac suggested staff take another look at widening the sidewalks, but said that if it requires the parking removal, then it won’t work for the community.”

Advertisement

The Bicycle Transportation Alliance (now The Street Trust) rep on the committee was John Sleavin. He said bike advocates compromised a lot over the two-year process. “Now all they’re asking for is a bike lane where it’s needed most,” the minutes state. “In the uphill climbing section of Hawthorne.”

There was some back-and-forth between bike advocates and PBOT about doing tests of bike lanes in various locations, “As painted lanes are easy to remove”.

Young Park, a rep for TriMet on the committee, dashed hopes of bike lane supporters when they said Alternatives 3A and 3B would, “impede transit operation on Hawthorne.” Park said the “incremental and feasible” approach of Alternative 2 was what Hawthorne needed.

At one point during that final meeting, PBOT traffic engineer Lewis Wardrip pointed out that, “The issue here is not congestion, but rather the slowing of traffic as a result of removing a travel lane and the effects on business, both good and bad.” “[Wardrip] noted that congestion is not necessarily a bad thing,” the notes state. Wardrip said less space for driving on Hawthorne could make it more of a stop-and-go environment like that on NW 23rd — another very busy commercial main street.

As for concerns about auto traffic diversion, the PBOT staff at the time said their models showed if it happened, the majority would go to other collector streets, not to local streets.

Klotz, the Oregon Walks co-founder, said whatever option was chosen should, “Make it likely that more people will use modes other than the automobile.”

Matt Brown, a PBOT staffer who led the committee, said (in his personal opinion) that Alternative 3A and 3B could work, “But it would be a different street than it is today.” In the end, he said if the bike lane options were chosen, they would not be supported by a majority of the community. “Changes should happen incrementally,” he stated in the notes.

In the end Alternative 2 became the official recommendation of the committee. It was the safest choice and made some minor changes that wouldn’t rock the boat. It called for safer crossings, but maintained existing auto and transit traffic volumes.

For bike users, the Hawthorne Transportation Plan resulted in several promises. PBOT would install new bike parking “oases” (the first of which were installed 10 years later), and would add traffic calming to nearby Salmon and Lincoln/Harrison streets. The plan also called for signage and markings to warn drivers about the presence of bicycle on Hawthorne. Sharrow markings were outlined in the plan but were never installed.

Most bike advocates at the time were not thrilled at the outcome. “[The plan’s] worth for bicyclists is still being weighed by Catherine Ciarlo*, executive director of Bicycle Transportation Alliance,” an article in The Oregonian on October 25th, 2000. “It’s a little harder from a bicycling standpoint to get excited,” she said. “But trade-offs were made.” (*Note: Ciarlo is currently manager of PBOT’s Active Transportation and Safety Division.)

It’s remarkable how close Portland came to painting bike lanes on Hawthorne in 1997. It’s also remarkable how close we came in 2021 to not doing it.

— Jonathan Maus: (503) 706-8804, @jonathan_maus on Twitter and jonathan@bikeportland.org

— Get our headlines delivered to your inbox.

— Support this independent community media outlet with a one-time contribution or monthly subscription.