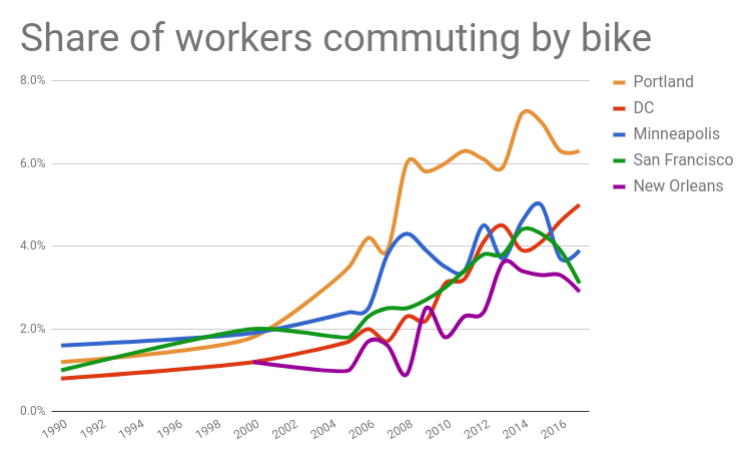

American bike commuting rates seem to have entered a post-recession skid in 2017. Here in Portland, meanwhile, they once again stayed about the same, according to Census estimates released this month.

About 6.3 percent of employed city residents got to work by bike in 2017, exactly the same estimate as in 2016.

About 27,000 fewer Americans reported daily bike-commuting routines last year compared to 2016, which was the second of two full years of low gas prices and the fifth year of rebounding suburbanization.

In Portland, the estimate was slightly more upbeat: about 6.3 percent of employed city residents got to work by bike in 2017, exactly the same estimate as in 2016.

In absolute terms, the estimated number of Portlanders who bike to work edged up by a statistically negligible 700 people, to 22,647.

New high for working at home, new low for driving alone

All charts: BikePortland. All data: 2017 American Community Survey, U.S. Census Bureau.

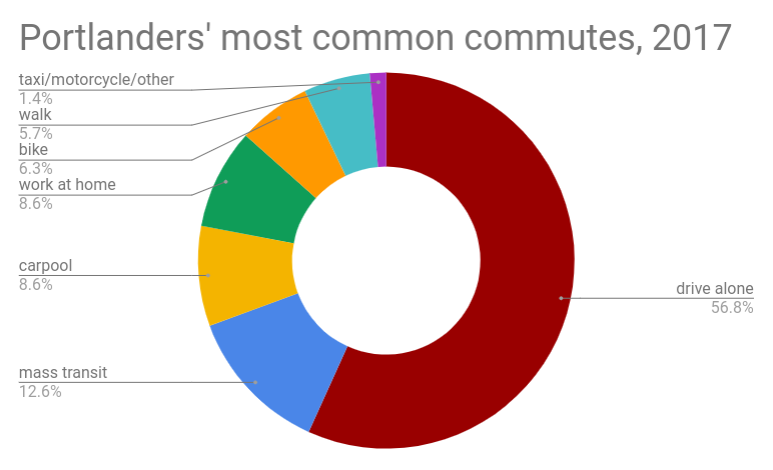

Public transit (13 percent), walking (6 percent) and carpooling (9 percent) were also virtually unchanged in Portland from past years.

The good news: Driving alone hit a new all-time low estimate, at just below 57 percent of workers. Ten years before, in 2007, the figure was 64 percent.

At this rate, drive-alone commuters would become a minority in Portland starting in 2027.

The total number of car commutes in Portland keeps growing, sadly. But it could be worse. If Portlanders still drove solo at the rate they were before the recession, the streets would be carrying 24,000 more autos per workday. Instead, those workers are biking, walking, riding transit, or working at home — which hit a new all-time high last year at 9 percent of Portland’s workforce.

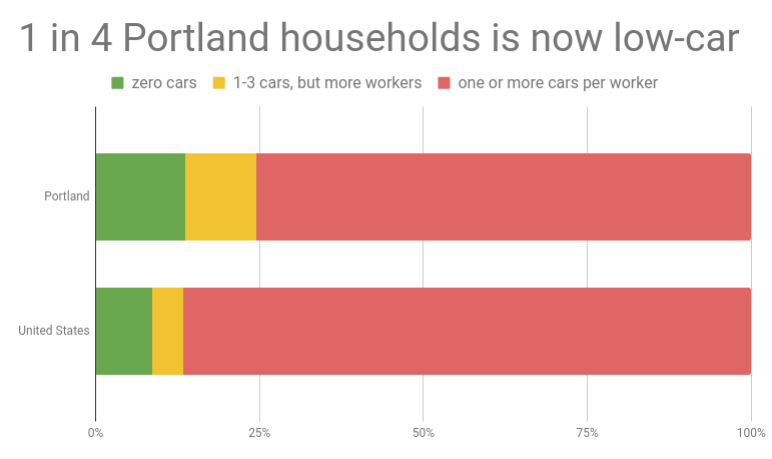

That mix of improving options may help explain why Portland’s auto ownership per capita has fallen. This month’s data showed the estimated percentage of Portland households that include more workers than automobiles hit another high in 2017: 24 percent, enough to account for about half the city’s net household growth since 2007. (No wonder there’s a continuing market for new homes without much auto parking.)

Nationally, the share of “low-car” households with workers is 13 percent.

The only big U.S. cities where biking probably rose were having major transit problems

Bike-commuting estimates, which are averages calculated from rolling surveys taken throughout the year, dipped noticeably last year in several leading U.S. bike cities, this month’s data revealed.

San Francisco reported a seven-year low of 3.1 percent biking; Oakland, a seven-year low of 1.8 percent; Seattle, a 10-year low of 2.8 percent.

(In Seattle’s defense, mass transit use hit a modern high of almost 23 percent.)

Minneapolis (3.9 percent), New Orleans (2.9 percent), Tucson (2.5 percent) and Chicago (1.7 percent) all continued statistical plateaus that may have dipped slightly over the last few years.

Showing upticks in biking were Washington, D.C. (5 percent), New York City (1.3 percent) and Philadelphia (2.6 percent). All three of those were all-time highs — but all three came amid significant subway issues that have driven transit commuting down faster than bike commuting in those places has risen.

Estimates for smaller cities are more volatile and less reliable, but this year’s trend in the nation’s college towns seems to be no better than in the cities. Eugene’s bike-commuting estimate was just 4 percent, down from the 7 to 9 percent range a few years ago. Madison and Missoula also posted 4 percent, their lowest in years. In Davis, Calif., the nation’s bikingest city, the 2017 estimate was 16 percent, down from a recent peak estimate of 25 percent in 2013.

Advertisement

Is Portland’s next bike boom around the corner?

There are three caveats to include with any Census data, especially one-year estimates like these.

The first: these are just estimates. The figures listed are more likely to be true than any other figure is, but in every case the truth could be a bit higher or lower. That’s why what really matters is multi-year trends: sample that piles on sample that piles on sample.

Second: These ratios aren’t good ways to measure which cities are “best for biking,” because they fail to reflect the presence of other good options like mass transit and they’re ultimately based on arbitrary city limits. (The national advocacy nonprofit I used to write for, PeopleForBikes, recently came up with what I think is a much better system for comparing cities to each other, but it relies on data that won’t be out until December.)

Third: These ratios reflect the investments we were making a few years ago, not the ones we’re making now.

So for Portland, it’s worth thinking about what these numbers mean. After a surge and dip, local biking rates are about where they were nine years ago — despite a new 40-mile neighborhood greenway network, public bike share system, five awesome open-streets festivals every summer and thousands of new homes and jobs close to the city center.

Maybe all those things are part of why our rates haven’t fallen further, like those in some of our peer cities.

At the recent rate, Portland won’t reach its 30 percent target for drive-alone commuting until 2055 — 25 years behind schedule. With every tick and tock of climate news I see, my own sense of urgency to reach that goal gets sharper.

But personally, for once, I’m optimistic about the future of biking in Portland. From the new freeway-crossing bridges in Lloyd and inner Northwest to Gateway’s bikeway network, years of activism are about to bear fruit. The long-awaited downtown protected bike lane network project is finally here, and it has the potential to be game-changingly good. It’s funded; it’s mostly planned; it has no organized opposition.

If a good chunk of it is built, it’ll not only be a dramatic upgrade to biking in the part of our city where people most want to bike, not to mention the complementary modes of walking and transit. It’ll also be an inspiration to the whole region, introducing hundreds of thousands of people to quality bike infrastructure and giving them a reason to fight for their neighborhoods to have some, too.

The biggest risk at this point is that not enough people will tell the city that they’re excited about it — and block by block, street by street, the forces of stasis will chip away at its quality.

But I don’t think that’s going to happen. When the political rubber hits the road, Portland’s dedicated biking community is second to none.

— Michael Andersen: @andersem on Twitter and mike.andersen@gmail.com.

Never miss a story. Sign-up for the daily BP Headlines email.

BikePortland needs your support.