(Photos: Jonathan Maus)

At a meeting of a high-powered Metro policy committee yesterday, the Oregon Department of Transportation was put in the hot seat over their plans to widen Interstate 5 through the Rose Quarter. Peppered with questions from Metro Councilor Bob Stacey, the regional director of ODOT Rian Windsheimer, was forced to came to the aid of an ODOT staff member who was presenting on the project.

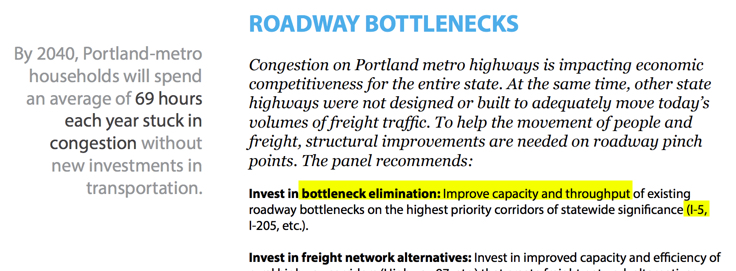

Windsheimer’s move demonstrated that sharp criticisms from a gathering storm of activists are gaining strength from elected leaders like Stacey, testing ODOT’s nerves and putting the agency on the defensive. The meeting also made it clear that, while initially sold by ODOT to the public and politicians as a “bottleneck elimination” project, the agency is now reluctant to claim it will lead to any capacity increase.

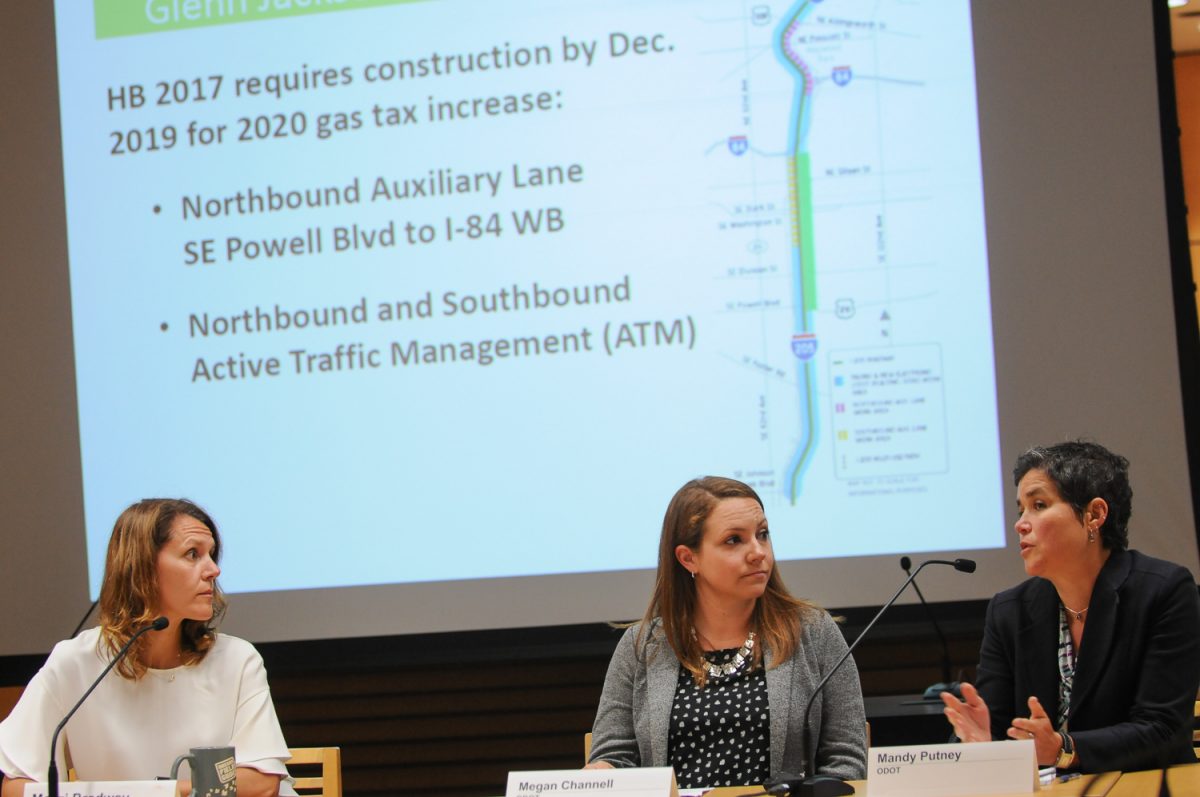

The exchange between Stacey, Windsheimer, and ODOT project manager Mandy Putney came after a presentation where another ODOT staffer, Megan Channell outlined three major highway projects the agency is working on. Projects that will add lanes to I-205, I-217, and I-5 are already slated to cost $1.1 billion — a number sure to increase when (or if) the projects are finished sometime around 2027. The I-5 Rose Quarter project is the most controversial of the three, given its proximity to downtown Portland and the historic Albina neighborhood.

“I don’t know how on earth we can reconcile any ostensible commitment to restorative justice for this neighborhood by poisoning the air to the point where we recommend children stay indoors.”

— Aaron Brown, No More Freeways PDX

In their presentation to the Joint Policy Advisory Committee on Transportation yesterday, ODOT said the I-5 project could cost up to $500 million when it’s all said and done. The State Legislature has already committed $400 to $420 million in bonding revenue via the transportation package they passed in 2017.

Prior to the presentation, the assembled committee members — including mayors and other elected officials, as well as senior agency staff from around the region — heard public testimony from Aaron Brown, leader of the No More Freeways PDX coalition. Brown offered stinging criticisms of ODOT’s plans for the Rose Quarter. He referenced the nascent Albina Vision plan which seeks to restore the historic neighborhood that existed in the area before it was razed for sports stadiums and freeways in the name of “urban renewal.”

“The project ODOT is proposing in this neighborhood,” Brown said, “Is directly antithetical to the transformative and restorative opportunity which the Albina Vision is promoting.” Brown also said the project will have a negative impact on Harriet Tubman Middle School, a school with a majority of low-income students of color. ODOT’s plans will carve into the existing planted area between the school and the freeway, putting a new lane within yards of its classrooms. “The school has such poor air quality that public health researchers recommended students not be given outdoor recess,” he said. “I don’t know how on earth we can reconcile any ostensible commitment to restorative justice for this neighborhood by poisoning the air to the point where we recommend children stay indoors. That’s out of a Ray Bradbury novel.”

Advertisement

Brown found a supportive ear in Metro Councilor Bob Stacey.

Stacey is concerned ODOT has taken the easy way out when it comes to environmental review of the project. ODOT has opted to do an Environmental Assessment (EA) instead of the much more rigorous Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) — a move that has also been flagged by environmental and social justice groups. Given the emergence of the Albina Vision plan since the project was adopted in 2012, and its proximity to a Title I school, Stacey invoked the Civil Rights Act in his call for a more robust analysis of the project’s potential impacts. ODOT staff assured him their assessment will be adequate; but Stacey told me in an interview after the meeting that, “I think it’s prudent of ODOT to use all the tools of engagement. My concern is that their EA won’t vet community concerns and I’ll be watching this very closely.”

Stacey also pressed ODOT staff about whether or not the project will increase capacity through the Rose Quarter, setting up a somewhat testy exchange.

“I presume that the State of Oregon and City of Portland believe more vehicles will be able to pass through this portion of I-5 as a result of this project?” Stacey questioned. “I happen to agree with Mr. [Aaron] Brown that they will go as slowly as the traffic does today once people adjust to the new capacity.”

“It will still be two lanes of I-5 northbound in, and two lanes of I-5 northbound out. It is not increasing — as you’re describing — a big throughput capacity.”

— Rian Windsheimer, ODOT

ODOT’s Mandy Putney then tried to explain that the I-5 project won’t add any new capacity. “Rose Quarter is an operational project,” she said. “We’re adding an auxiliary lane to allow people to merge more easily between very closely spaced ramps… Rose Quarter will have the same number of general purpose lanes in the future as it does today.”

Stacey replied, “Will it have increased capacity though?”

“It will allow people to move more safely through the area,” Putney replied.

At that point ODOT Region 1 Director Rian Windsheimer interjected, “It will still be two lanes of I-5 northbound in, and two lanes of I-5 northbound out. It is not increasing — as you’re describing — a big throughput capacity. It’s allowing what’s there today to function better. There will only be two lanes in and two lanes out… it’s the same. This is about allowing the high volumes from I-84 to merge into that same area.”

Merging and safety aside, ODOT’s own presentation yesterday pointed out that the project will save an estimated 2.5 million hours of vehicle delay each year. If people are able to drive more quickly through this section of freeway, isn’t it obvious that more of them will move through it?

ODOT’s reluctance to openly admit a capacity increase is noteworthy. When political groundwork was laid for this project, “reducing congestion” and “bottleneck elimination” were key to winning over the public and legislators (see above). But now that funding is secured, they say it’s all about safety and operational improvements. More capacity wasn’t mentioned when ODOT’s Megan Channell stated the project goal yesterday: “To create a safer and more reliable I-5, a better connected community, and an opportunity for economic growth.”

In a post-meeting interview Stacey said, “I think that’s a refreshing acknowledgment that this is not a project that will help traffic move more freely. It will reduce the number of fender-benders that occur in that area. That might allow a little bit of 35 mph travel instead of 20 mph travel; but as he [Windsheimer] says, they don’t expect it’s going to make a difference in terms of through-put.” “Fair enough,” he continued. “So again, why do we need to spend this much money?”

Stacey also sees a bit of a bait-and-switch in the way ODOT has sold the project to the public. “It [the honesty about no capacity increase] is a little late in terms of overall public decision-making, including the legislative decision-making,” he said. “I don’t know if anyone from ODOT expressly told the committee [of legislators in Salem], ‘Hey, just so we’re clear, there’s not going to be a single additional truck going through there, we’ll just have fewer dents on the trucks.”

— Jonathan Maus: (503) 706-8804, @jonathan_maus on Twitter and jonathan@bikeportland.org

Never miss a story. Sign-up for the daily BP Headlines email.

BikePortland needs your support.