This is the second of a two-part article by Aaron Brown, founder of No More Freeways PDX and former board president of Oregon Walks. The first part is here.

So, candidly, if freeway expansion is so obviously detrimental to the TriMet’s goals and ability to provide service to the region, why has TriMet supported it? Urban scholar Jacob Arbinder wrote in Democracy Journal last month about the bumbling, abysmal state of transportation governance in cities like New York and Boston. The piece is worth reading at length; he identifies the problem as a “broken political economy,” which is a fancy, academic way of stating that transit agencies suffer from a dearth of adequate democratic mechanisms for community input and budgetary accountability.

Put another way, if agencies, politicians and bureaucrats aren’t afraid of professional consequences for substandard service delivery, they have less incentive to stick their necks out to address the logistical and political circumstances preventing their buses and trains from running on time. To quote Arbinder:

“This is the crux of the urban mobility crisis: not broken infrastructure, but a broken political economy—one that includes transit but extends to issues far beyond it. Many thousands of voters do care about having fast, reliable trains and buses, and good advocacy organizations work to support their cause. But the number of politicians who believe the quality of the transit their constituents use will affect their chance of re-election seems to dwindle by the year….the implications of this problem suggest that progressives in urban America must not content themselves to effect change within the institutions of local government as they currently exist. Rather, they must articulate a vision for the future of their cities that begins with a wholesale reexamination of the structure of urban government itself.”

Arbinder doesn’t mention TriMet, but his criticisms match up neatly with what advocacy all-stars OPAL – Environmental Justice Oregon and their partners have been saying for years. Only one of seven TriMet Board of Directors tasked with oversight of the agency is a frequent transit rider; the board is appointed by Oregon’s Governor, and thereby significantly inoculated from the pressures to oversee successful governance faced by locally elected officials closer to the ground (and, therefore, constituents).

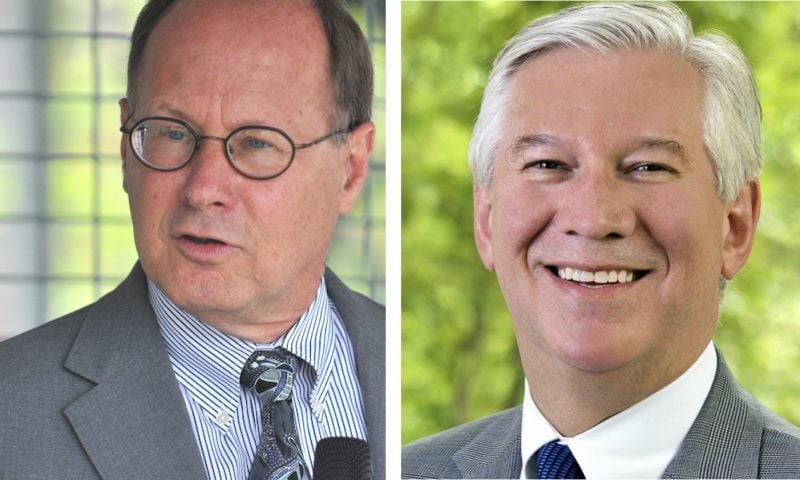

(Left: Neil McFarlane, photo by J. Maus/BikePortland – Right: Doug Kelsey, photo by TriMet)

The national search for Niel McFarlane’s replacement concluded with one finalist candidate for General Manager, who appears to be McFarlane’s hand-chosen successor. Whether it’s on issues of budgeting for policing, fare enforcement, paperless passes, or choices about which transportation megaprojects the agency chooses to support, it’s difficult to agree with McFarlane’s assertion (to The Oregonian) that TriMet as an agency currently functions as “a very responsive system” when community members have no meaningful mechanism to hold the agency accountable.

It’s difficult to agree with McFarlane’s assertion that TriMet as an agency currently functions as “a very responsive system” when community members have no meaningful mechanism to hold the agency accountable.

The most charitable take on TriMet’s willingness to consider the three-freeway-expansions-for-a light rail line bargain proposed last year stems from an agency with an outdated understanding of the region’s needs and electorate. TriMet would rather partner with ODOT to scheme for joint projects than disprove the notion the region would fund transit without also doling out freeway expansions to sprawl-hungry Washington and Clackamas counties.

This strategic conservatism is unwarranted; I’d argue it’s wholly counterproductive. Atlanta, Sacramento and San Diego have all recently lost regional transportation funding initiatives that focused on that elusive “balance” to placate suburban voters with freeway money. Meanwhile, Los Angeles and Seattle won $120 billion and $54 billion for massive, transformative packages that were exclusively transit-oriented. Seattle’s example is especially notable; their robust victory in 2016 that will transform the Puget Sound is preceded by ballot box failure ten years earlier, with a package that included significant funding for roads. The inclusion of freeway funding in the 2006 package didn’t mollify suburban voters’ tax skepticism, and proved unpalatable to Seattle’s progressive voter base. It’s not difficult to imagine a parallel where Clackamas County’s tax skepticism, Washington County’s changing demographics and Multnomah County’s distaste for milquetoast climate policy leads to similar electoral defeat.

Besides, it’s worth reiterating: even a successful “political compromise” that wins at the ballot with massive new freeway expansion but loses at the hard facts of science is still a loss. The region’s still stuck in gridlock, we waste a billions in taxpayer money, and we continue to fry the planet. No one planning on being alive in the next few decades should consider this an acceptable outcome.

Advertisement

In this light, freeways look increasing like pipelines, prisons, coal plants and landfills: massive public works that unnecessarily subsidize society’s most destructive, unsustainable and unhealthy practices and behaviors, funded by a well-connected, bipartisan lobby for government contracts that allocate burdens on depressingly familiar lines of race, class and geography. As an opinion piece in The Guardian put it, “Progress in the 21st century should be measured less by the new infrastructure you build than by the damaging infrastructure you retire.”

Too many advocacy groups, elected officials, and agencies are approaching our region’s woes from the unimaginative position of “what broken institutions do we have to work with” as opposed to instead asking “Where should our region be in the next twenty years, and what political coalition realignments and structural reforms must we make now to get there?”

Selling public transportation to Portlanders should be like selling hockey to Minnesotans. Aside from our oft-cited history as land-use innovators, the share of the Portland region who falls into the category of the Rising American Electorate continues to grow. Better transit service and access to walkable communities is a policy that the various factions of the Rising American Electorate enthusiastically support, given its overlapping connections to justice, housing, and climate. Turning these constituents out to vote for, say, college student bus passes is only a difficult lift if TriMet isn’t actively in cahoots with organizations who turn out community college students to vote.

Similarly, scholarship suggests America is seeing a wholly under-discussed resurgence of community organizing in the suburbs. The soccer moms (and after working on school bonds, I use the term “soccer mom” with revered endearment and appreciation) that hold their communities together with substantial unpaid volunteer work with PTAs, book clubs, and soccer teams are quite naturally talented at organizing community action; they do so every week just keeping their family’s errands on schedule and economic well-being afloat. They’ve successfully turned out the vote for numerous enormous school bonds across the region in the past few years, and have been instrumental in many of The Street Trust’s recent wins for Safe Routes to School funding.

Groups like Business for a Better Portland are beginning to challenge the notion that Portland’s business leaders are monolithically committed to last century’s broken infrastructure and austerity politics. Metro, the regional government lining up major regional campaigns for massive investments in housing, parks and transportation, would greatly benefit with TriMet as a partner in pushing for healthier, forward thinking solutions and retiring outdated ideas.

Until political careers are made or broken by one’s ability to integrate the voices of these political factions into TriMet’s decision-making and visioning process, the entity will remain wholly incapable of directing resources towards investments and policies, and campaigns for public support that serve these needs. A TriMet governed with these interests in mind would understand the need for greater skepticism for freeway boondoggles. This is the sort of accountability that OPAL is demanding from TriMet; the simple, radical notion that, to quote Saint Jane (Jacobs), “Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.”

Our region’s transportation system is the connective tissue to communities across four counties and two states. It’s difficult to overstate how firmly the efficacy of our streets, buses and sidewalks fundamentally shapes our economy, our communities, our health and well-being, our lives. Too many advocacy groups, elected officials, and agencies are approaching our region’s woes from the unimaginative position of “what broken institutions do we have to work with” as opposed to instead asking “where should our region be in the next twenty years, and what political coalition realignments and structural reforms must we make now to get there?” As our planet veers into climate calamity and our region experiences continued growth and inequality, anything short of an honest reassessment of which infrastructure and programs our local government should support — and which to retire — is simply institutionalized and intergenerational theft and violence.

And candidly, if Mr. McFarlane and other top regional leaders have spent so many years navigating these agencies and they still fail to see how crucial bold leadership will be in the decades ahead as Portland navigates these overlapping challenges; well, it appears to be an appropriate time to wish them all well on their future endeavors. Let’s hope that TriMet’s next GM and future Board appointments choose to address these structural shortcomings and align themselves as accomplices in the creation of fulfilling communities and faster commutes — instead of freeway congestion.

If you’d like to get involved with OPAL’s campaign to address TriMet’s lagging engagement with the community, check out their website (and be sure to chip in a couple bucks to OPAL while you’re at it). They’re holding a rally at the next TriMet Board hearing at 9:00am, March 28 in downtown Portland.

If you’d like to help us stop this dumb freeway, check out the No More Freeways website, and throw us a couple bucks if you’d like us to mail you a button.

— Aaron Brown has held leadership roles in campaigns to raise over $950 million in local funding for public schools, sidewalks and regional parks, including the 2016 Gas Tax and the 2017 Portland Public School Bond. He served as board president of Oregon Walks for nearly four year. He lives in North Portland and gets around town with his Surly Crosscheck and the Number 4 Bus. And yes, on occasion, he drives. He’s online at @ambrown on Twitter and his personal website.

Never miss a story. Sign-up for the daily BP Headlines email.

BikePortland needs your support.