Jim Howell embodied the visionary courage, tireless idealism, and civic activism that helped put Portland on the map as one of America’s most hopeful cities in the 20th century. He died Sunday, May 26th at the age of 90.

In September 1969, Howell and two friends founded an ad hoc group called Riverfront for People. Howell was an architect at the time and nurtured a side interest in civic organizing. As his firm worked with the City of Portland and the Model Cities program to help design Portland parks (including Woodlawn Park and the picnic shelter at Mt. Tabor Park that was unfortunately destroyed by a tree back in January), his interest in transportation planning — and specifically transit — grew. Just five years after he watched the I-5 freeway obliterate access to the east side of the Willamette River, and with the federally-funded freeway industrial complex hell-bent become an all-powerful influence on Portland’s urban form, a report by City Club of Portland caught Howell’s attention.

The 1969 report warned that if the downtown waterfront gives into an, “overemphasis on economy of traffic movement and disregard of other values, it will be little used and will contribute nothing to the central city’s vitality.”

The west side’s waterfront was already besmirched by Harbor Drive, a four-lane freeway completed in 1942. According to writer Tim DuRoche, When ODOT proposed widening it in 1968, Howell and his architect friend Bob Belcher read the City Club report and (at the prodding of Bob’s partner and civic activist Allison Belcher) decided to take its warnings to heart.

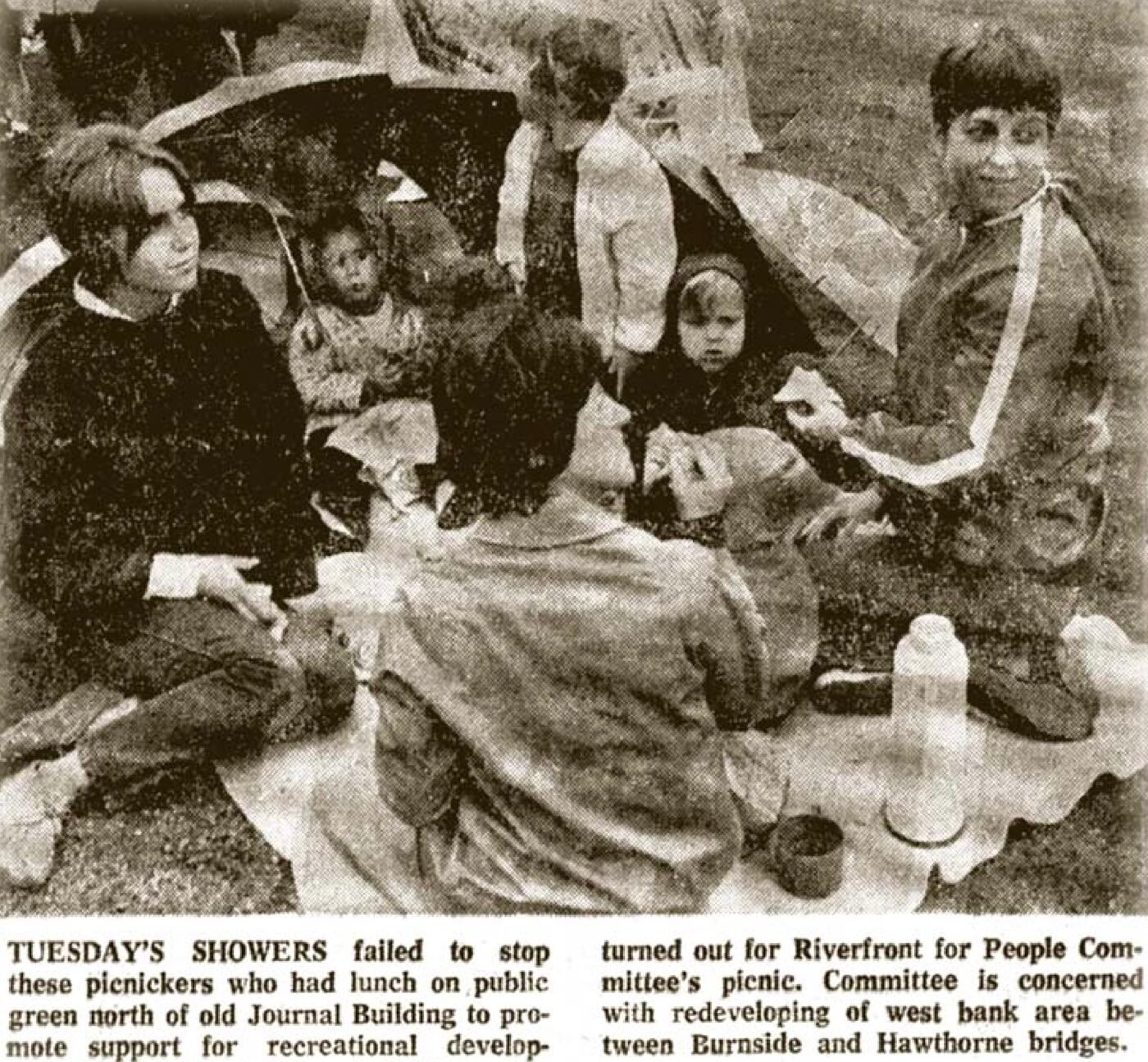

On August 19th, 1969 Howell and the Belchers organized a protest picnic on a grassy median adjacent to Harbor Drive’s freeway lanes. Around 400 people (including 150 children) showed up.

Historians recognize that protest as a seminal moment in Portland’s proud history of transportation reform activism. Ultimately, Harbor Drive was removed, and the successful picnic gave Portlanders their first taste of how civic power could be harnessed to alter the politics of transportation plans. And it sparked Howell’s lifelong passion for activism.

It’s quirk of history that Howell’s formative, freeway-fighting picnic happened in 1969 — because that’s the same year Senate Bill 10 (precursor to Oregon’s landmark SB 100) enshrined land-use planning requirements into state law, the Mt. Hood Freeway was approved, and the transit agency TriMet was created.

Doug Allen came to Portland in 1968 to attend Reed College. Hoping to land a writing gig and take up the transportation beat at upstart newspaper Willamette Week, Allen walked into the office of the paper’s founder Ron Buel (who’d go on to work with Allen and Howell as a major player in transportation activism) and asked for an assignment. “He said, go talk to this Jim Howell guy, he’s an architect promoting a grid system for busses.” Allen recalled in an interview with BikePortland.

“So I went up to his office and Jim showed me all the maps he’d made showing how the system ought to work.”

Allen (now Vice President of Association of Oregon Rail and Transit Advocates) and Howell became fast friends and fellow rabble-rousers. In 1975 they formed “Citizens for Better Transit” with another activist, Ray Polani. One year later the trio served together on the Banfield Citizens Advisory Committee, which looked at alternative ways to spend funds set aside for the Mount Hood Freeway. Howell also helped organize Sensible Transportation Options for People (STOP) a group that helped kill the Mt. Hood Freeway project — another huge milestone in Howell’s early activism.

With defeats of Harbor Drive and the Mt. Hood Freeway, and political leadership that favored land use and air quality considerations ahead of freeway megaprojects and auto driving throughput, Howell and his cohort had the wind at their backs. And instead of fighting against something, they wanted to fight for something. That’s when Howell’s attention turned to designing a more effective transit system.

“At some point, around 1977 or so, we had this discussion and said, ‘We’re not accomplishing all that much from the outside, we really need to get on the inside,'” Allen shared. “So Jim applied for a job at TriMet and was hired as a planner.”

Mike Kyte, the TriMet manager who hired Howell, remembered him as a champion for a grid transit network structure for Portland’s bus system. “Though what emerged wasn’t totally what he proposed, his ideas certainly influenced us as we revamped the region’s bus routes.” Kyte also credited Howell (and influential former TriMet planner Tom Matoff) for creating TriMet’s successful timed transfer system that opened up transit for suburban riders in Washington County. It worked so well, Kyte recalled, that he used it to replan San Diego’s bus system years later.

Several people I heard from for this article noted that Howell’s urging for TriMet to not follow the typical hub-and-spoke system model — and instead create a grid network with transfers to allow multi-destinational trips — was some of his most important work.

Allen said Howell understood that, “You shouldn’t just feed everything to downtown,” and that TriMet should create a network that emulates what you can do with the highway system, “Where people can go anywhere they want and where you don’t have to live on a particular road to be able to go to some other place that’s on that same road.”

Noted transit consultant and author Jarrett Walker was an intern at TriMet when these ideas were first introduced and Allen says Walker, “Picked up the whole concept and really ran with it.”

One source who worked with Howell at TriMet remembered him as a, “Funny, upbeat, true original,” who was, “definitely under-appreciated” for his contributions to the transit agency.

Another admirable aspect of Howell’s approach was his willingness work with younger activists — whether that meant marching with them at a protest, talking to a young reporter, or showing up to one of our Wonk Nights.

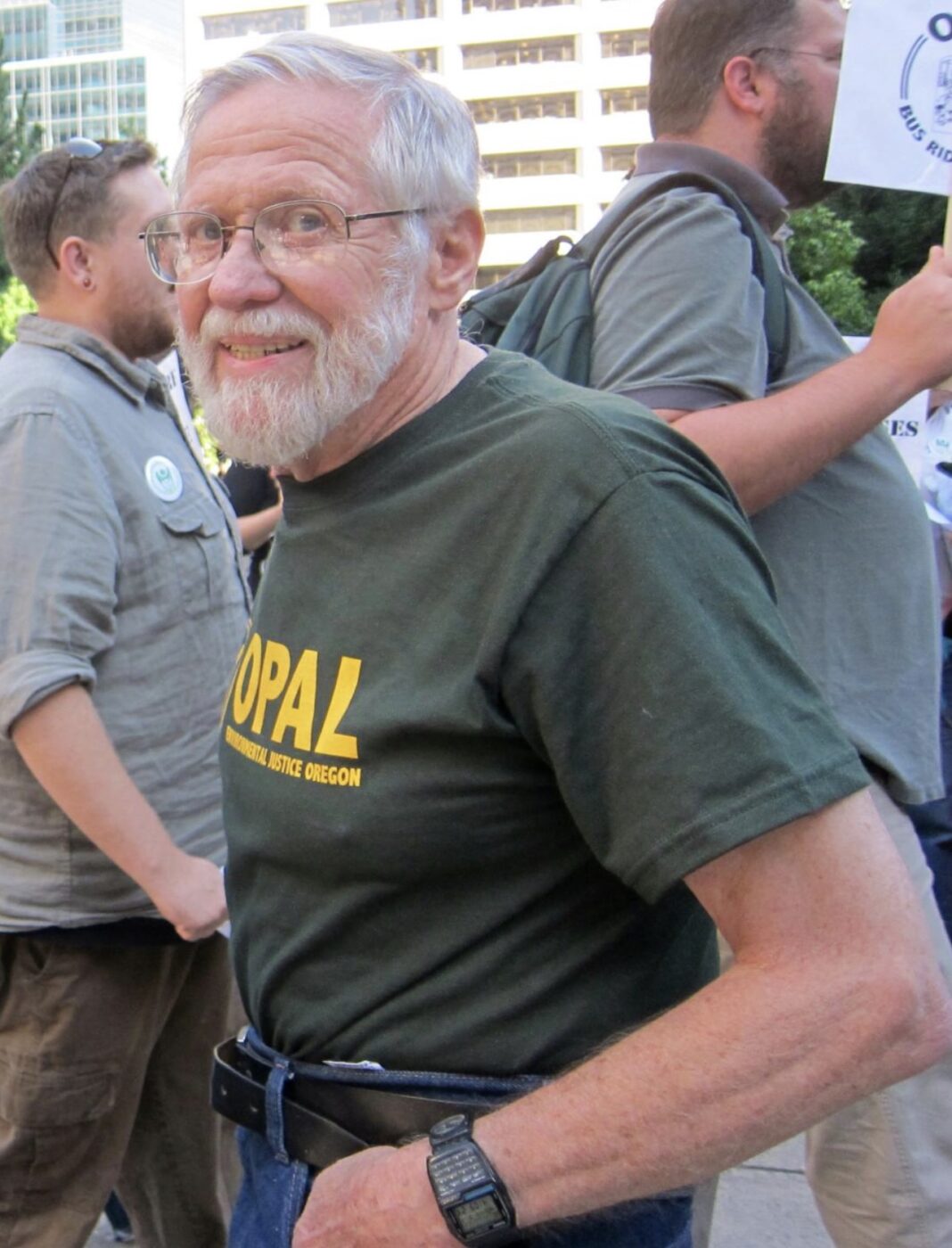

One early morning in 2018 I cycled to a protest against the I-5 Rose Quarter project on the N Flint Avenue bridge and there was Howell and his friend Ron Buel passing around petitions. Howell also worked closely with nonprofit OPAL Environmental Justice Oregon and their Bus Riders Unite program. Former OPAL Executive Director Joseph Santos-Lyons recalled that Howell volunteered to help organize transit-dependent high school students. “Jim was one of the elders who thoughtfully and kindly shared his wisdom from a generation of advocacy and helped OPAL become a leading voice for transportation justice.”

Former BikePortland reporter Michael Andersen (now a senior researcher at Sightline) recalled seeing Howell at the first ever Bus Riders Unite protest against a TriMet fare hike proposal: “I think when you’re young, you tend to see age as a big dividing line in the political world. It’s just a little unusual to see an older person involved in efforts to change the way things are, unless they have some very personal stake in the matter. But there Jim was the first time I remember meeting him, a seventy-something wearing a green OPAL t-shirt tucked neatly into his pants, marching in a circle outside City Hall with folks who were mostly decades younger and several shades browner.”

Abby Griffith, a transit activist and community organizer with OPAL, told BikePortland Howell had not missed a monthly Bus Riders Unite (BRU) meeting since she joined the organization in October 2022. “My favorite memory of Jim is his advocacy for making the Hollywood Transit Center accessible to everyone,” Griffith shared. Howell was the BRU spokesperson for the Hollywood HUB Plan, which, in a 2023 letter to TriMet on BRU’s behalf he said, “Will seriously degrade the safety of transit riders transferring between MAX and buses as well the bus riders who will be in the new housing.” Then in typical Howell fashion, that statement was followed by a list of 10 bulleted items with specific requests for changes.

Portland Mercury Reporter Taylor Griggs first met Howell as a new writer for BikePortland without much experience on local transportation issues. “But even though I was young, inexperienced, and naive, Jim took me seriously and would call me from time to time with story ideas or things he wanted to talk about.”

Ideas were what drove Howell. Whether it was a “common sense” alternative to the failed Columbia River Crossing, a downtown MAX tunnel, or his Purple Line light rail and elevated bikeway concept, all his ideas needed were an open mind and a willing ear.

Allen thinks the “craziest idea” Howell ever had was one he actually made a reality: a bus line between Portland and Tillamook on the Oregon Coast. “Jim came to me and said, ‘You know, we oughta’ run a bus line out there. We can use our principles and make it work’. Doesn’t that sound like a stupid thing to do?” Allen recalled. But eventually Howell convinced him.

Despite Greyhound and other operators losing money on the service and all but giving up on the route, Howell and Allen founded Citizens Better Transit Inc. (that name sound familiar?) and launched the “Beach Bus” in 1984. Allen said they added a second round trip and extended service up the coast to Seaside. “We basically doubled the amount of service Greyhound provided and we had four times the ridership they had,” Allen said. And six years later it was successful enough to sell back to Greyhound.

It didn’t matter if Howell was an agency staffer, an organizer, an agitator, or an entrepreneur — he was always a change-agent motivated by a passion for better transit and a better city. He used many of the same tools and strategies of other activists, but managed to combine them into an inside-outside approach that led to lasting changes that influence how we all move around and a legacy that will be studied by future generations.

Howell’s resume and longevity are a testament to his selfless, apolitical approach. He never sought personal credit and considered himself a technocrat. “He was ingenious and full of energy,” Allen recalled. “And he was active in these fights right up until the end.”

Thankfully Howell’s end isn’t the end of his ideas. The example set by Howell, and his willingness to share knowledge with younger generations, means his fight for a better city lives on in all of us.

Rest in peace, Jim.