Last week, the Bureau of Development Services (BDS) posted the summary notes of the Early Assistance meeting between the developers of the Alpenrose site and the city permitting bureaus.

I was probably a happier person before I knew what all that meant.

But I’m trying to understand how it has come to pass that, over half a century after the southwest was annexed to the City of Portland, the quadrant persists in having such bad sidewalk coverage and incomplete bike facilities despite steady growth in population and new buildings.

Understanding the nitty-gritty of “why” ends up being a wonkfest at the intersection of transportation and land use policy. But that wonkiness goes down a little easier if you can watch decisions roll out in real time.

The high-profile Alpenrose housing project which has begun moving through Portland’s development review system provides an opportunity to do just that. And the notes from the Early Assistance meeting are the public’s first peek at the decisions the Bureau of Environmental Services (BES) and the Portland Bureau of Transportation (PBOT) will make about sidewalks and bike lanes. These early decisions determine whether sidewalks and bike lanes will be built at all.

The development

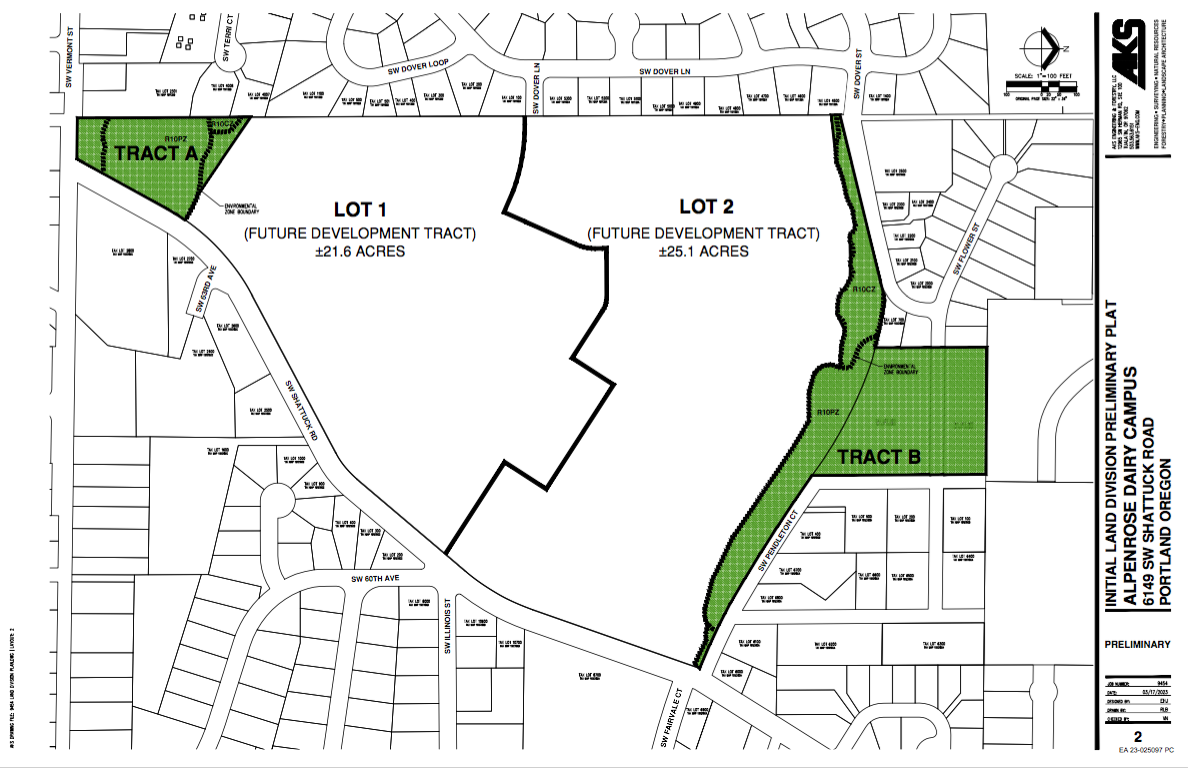

The developers have proposed dividing the 51-acre property into approximately 307 lots of attached and detached houses. Depending on the ratio of attached to detached houses, some of the detached houses could still come with a generous lot size, say a quarter of an acre.

A 51-acre development proposal is unusually large for Portland, and the Alpenrose project will be the first of its kind coming under review since “Missing Middle Housing” legislation was adopted at both the local and state levels.

You might recall that the recent middle housing zoning changes allow homeowners to build up to four units on most residential lots. In Portland, this new zoning policy was called the Residential Infill Project (RIP), and the City Council adopted it in 2020. The council was not unanimous in its decision to loosen zoning regulations, but proponents argued it was necessary for dealing with housing scarcity, and also as a response to racist and exclusionary zoning policies.

The catch is that the future owners of each of the 307 new Alpenrose lots will also be allowed to exercise their “missing middle” zoning rights. That means they could add more dwellings to each property. Thus the 307 units could expand into a “reasonable worst-case scenario” that would overwhelm area infrastructure, particularly transportation. As BDS noted,

ORS does not allow us to impose conditions of approval that would disallow middle housing development types; at this point staff needs to understand more about the challenges to infrastructure and specifically transportation limitations before being able to weigh in on whether the proposal is approvable or not as proposed, or what conditions of approval would be enforceable or desirable to address the issues.

It continued, “the importance of addressing the infrastructure challenges with this site cannot be overstated.”

PBOT also weighed in,

Adequacy of services findings and compliance with the comprehensive plan policies needs to be analyzed based on the anticipated demand from the full buildout potential of the requested zoning.

I don’t know if RIP proponents had vast tracks of new development in mind when they crafted the zoning changes, but the bureaus appear to be wrestling with a “dog catches car” scenario of too many houses for an inadequate transportation system.

Active transportation and the two-bureau shuffle

The specific purpose of the Alpenrose Early Assistance meeting (also known as a Pre-Application Conference) was to discuss the Comprehensive Plan Map and Zoning Map Amendments, as well as a Land Division Review, which the extensive development plan would require.

Early Assistance meetings are organized as an exchange of information which lets various bureaus comment on requirements and key issues in advance of the developer submitting an application.

And this is where the two-bureau shuffle begins.

From a transportation point of view, the most relevant Early Assistance comments come from BES and PBOT. What is important to understand is that BES is in the driver’s seat, PBOT cannot do much unless BES agrees to build new stormwater facilities.

PBOT starts out strong, “The applicant should anticipate sidewalk and bicycle facility construction along SW Shattuck Rd. and SW Vermont St. for the entire length of the parent parcel at the time of the future development.”

Quickly back tracks, “some form of pedestrian and bicycle improvement is needed in the public right-of- way, but it is anticipated that full standard improvements may not be feasible.”

And concludes that “If improvements are not fully waived, then a Public Works Permit is needed to inform approval of non-standard improvements through the Public Works Alternative Review process.”

PBOT went from requirement to waiver in three short pages.

The Public Works Alternative Review (PWAR)

The quote above mentions the Public Works Alternative Review. The PWAR is a process whereby an applicant can request allowance to build an alternative design to standard improvements in the public right-of-way, if for some reason the city decides that standard frontage improvements like sidewalks and bike lanes cannot be built.

About the Alpenrose project specifically, PBOT writes that,

It is anticipated the applicant will wish to propose an alternative to the standard given the terrain and natural resources present for some portions of the existing rights-of-way.

PBOT doesn’t mention lack of stormwater conveyance as a reason that a sidewalk can’t be built, but Shattuck, like most southwest Portland streets, drains its stormwater into area streams. A sidewalk would require a bioswale or a stormwater basin to treat sidewalk run-off, like the ones the city built off of Capitol Highway.

The PWAR committee is composed of managers from PBOT, BES, Water, and Urban Forestry. Their decision process is not public. It is a black box which tends to output tersely worded requirements such as, “The applicant shall provide a minimum 6-ft wide paved shoulder widening.” Unfortunately, PWAR is where sidewalks and bike lanes go to die.

Throughout the document, PBOT and BES defer to PWAR decisions as if they weren’t involved with making them. Here’s BES,

Frontage improvements as described by PBOT may trigger stormwater management requirements. If frontage improvements must be built with this land division (depending on the results of any requested Alternative Review Committee decisions) and the improvement trigger stormwater management requirements, BES will require approved PWP Concept Development …

If BES does not want to build public stormwater facilities, the PWAR solution usually has pedestrians walking at grade with cars, either on the road or to the side of it along a goat path.

What happens next

The next step in the development review process will be the actual Public Works Alternative Review decisions themselves. Those will be the first indication of the city’s support for safe spaces to walk and bike. Those decisions bake-in the frontage requirements early in the process, and the whole subdivision will be designed around them.

PWAR decisions are available with a public records request.

Lawyering up

One of the most curious paragraphs in the Early Assistance Summary comes from PBOT and advises the applicant about defending against legal challenges:

If the proposed land division is challenged or opposed by neighbors or the area’s neighborhood association, PBOT will not have any supporting documentation in the record to refer to other than the applicant’s narrative. This is raised because of similar experiences in the past when other partition proposals were challenged, opposed to or appealed. In those cases, applications were required to be placed on hold for information to be collected, prepared and submitted, or applications were fundamentally denied due to the lack of adequate and credible evidence in the record. PBOT staff may be able to determine that the project will not result in detrimental impacts to the surrounding transportation system or immediate neighborhood, but the applicant is advised that if the decision on this project is appealed, the higher decision-making bodies have not (solely) relied upon PBOT’s assessment and/or recommendation. The applicant is referred to Zoning Code Section 33.800.060 which states that “the burden of proof is on the applicant to show that the approval criteria are met; the burden is not on the City or other parties to show that the criteria have not been met.”

And the truth is that that the entire process can be litigious. What PBOT doesn’t mention, possibly because this document is in the form of a memo between city bureaus and the developer, is that another worry the city has is that it will be sued by the developer.

This can happen if the developer feels that the city is trying to exact too much from them in terms of public works, like providing expensive stormwater facilities for sidewalks, for example. The body of jurisprudence regarding these types of suits is referred to as Nollan/Dolan.

Keep in mind that “Dolan” is Dolan v. City of Tigard, a case decided in 1994 by the U.S. Supreme Court which is considered a landmark regarding zoning and property rights. The Dolans did not want to dedicate land for the adjacent Fanno Creek Trail.

That land use decision occupies significant real estate in Portland’s mind.

Wrapping it up

I’m eager to see the PWAR decisions. If they follow the usual “southwest rules,” Shattuck will get a treatment similar to Gibbs St. Or maybe the PWAR will select a treatment out of the alternatives in the Pedestrian Design Guide.

On the other hand, allowing over 300 new housing units to be built without a sidewalk on the northern Lot 1 and Lot 2 portions of the property is outrageous, and might be challenged.

Stay tuned.