Being stopped in traffic is the most common way most people come into contact with the police, but we don’t all experience those stops equally. In Portland (and throughout the United States), people of color are overrepresented in traffic stops, with Black people experiencing the most drastic effects of this bias. And this is more than an inconvenience: Black people across the country have been killed by cops using lethal force during otherwise routine traffic stops.

As a result, advocates have taken on this issue as both a racial and transportation justice cause, and Portland officials have indicated they want to make a change. Last summer, Mayor Ted Wheeler and Police Chief Chuck Lovell directed Portland police officers to make fewer traffic stops, especially for offenses deemed low-importance, where racial bias is more prevalent.

“We need to focus on behaviors that result in serious or fatal crashes, such as speeding, driving while impaired, distracted driving, etc.” Lovell said in a press release last year. “Stops for non-moving violations or lower level infractions will still be allowed, but they must have a safety component or have an actionable investigative factor to it.”

A report on 2021 traffic stops released by the Portland Police Bureau (PPB) earlier this month sheds light into what – if anything – has changed in the year since. The big takeaway? Despite a serious drop in traffic stop rates, large racial disparities remain.

PPB’s traffic stop rates were way down in 2021 – the report says PPB officers “performed 44 percent fewer driver stops and 80 percent fewer pedestrian stops than in the prior year.” But this is not necessarily as a result of Wheeler and Lovell’s instructions, and it didn’t appear to make an impact on the racial biases shown against Portlanders of color. Instead, it appears to be because of a staffing shift that sent the Bureau’s Traffic Division into disarray.

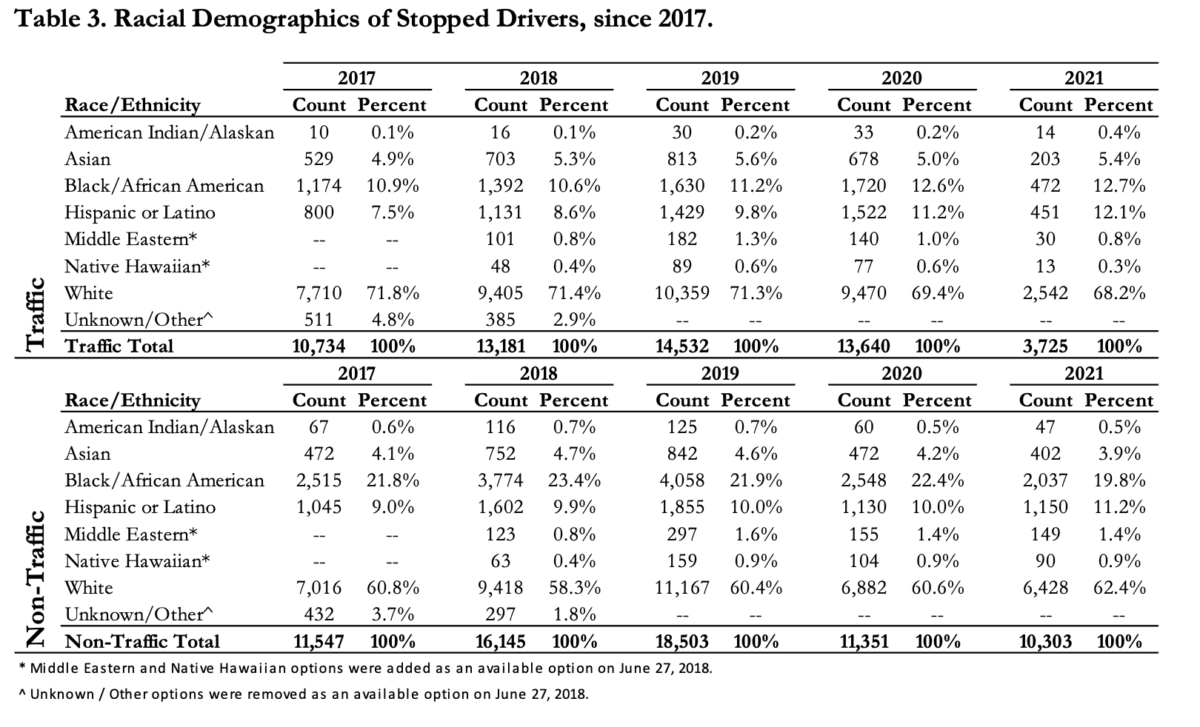

Before 2021, there were two groups of officers – from the Traffic and Non-Traffic Divisions – making roughly the same number of traffic stops each year for different reasons. The stated mission of the Traffic Division is to “address behaviors of road users, including drivers, bicycle riders, and pedestrians, that might lead to a collision.” The Non-Traffic Division’s goal “primarily relates to the reduction and prevention of violent crime in the City” and involves “discretionary traffic stops to contact potential subjects of interest.”

These discretionary stops are often made for offenses Wheeler and Hovell deemed “low-level” – i.e., an expired license plate or missing tags. They also leave a lot more room for officers to use their own – potentially racially biased – judgment. Even after Wheeler and Lovell guided officers to avoid those stops, the bulk of Non-Traffic Division stops were for offenses deemed minor.

Differences in calculating racial disparities

PPB uses its own benchmarks to compare their data on citywide racial demographics to calculate disparities. Recent census data indicates Portland’s Black population sits at about 5.9% of the total. Even though the actual number may be slightly higher due to census counting errors and a growing population, this percentage is generally accepted and has been used in the past to indicate racial profiling within PPB traffic stops.

According to the report, Black people made up almost 18% of the population stopped in traffic in 2021 – meaning they are overrepresented threefold. But PPB’s internal data says otherwise.

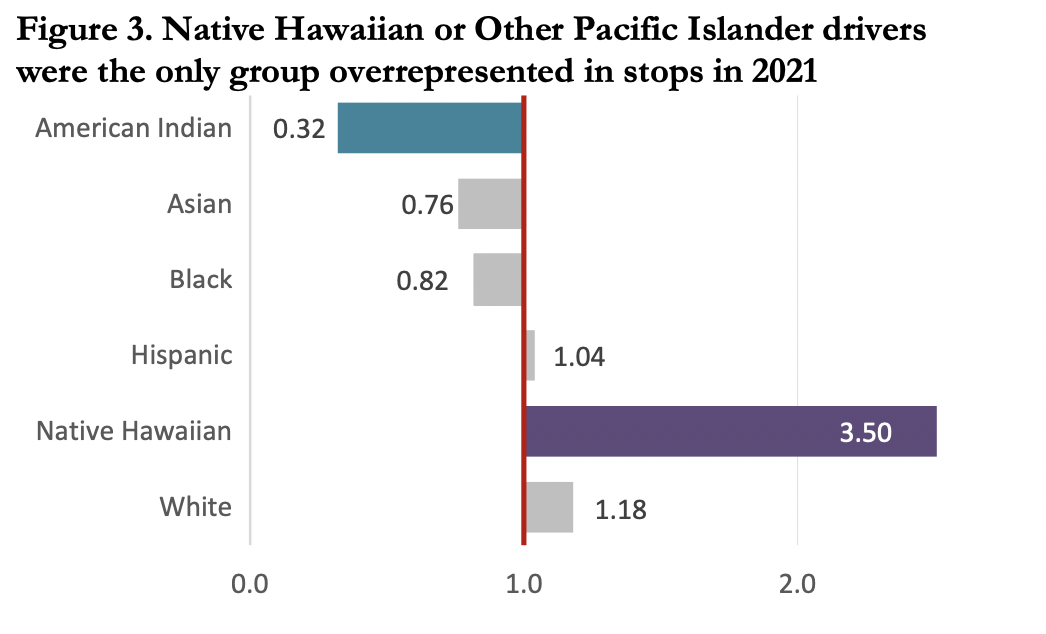

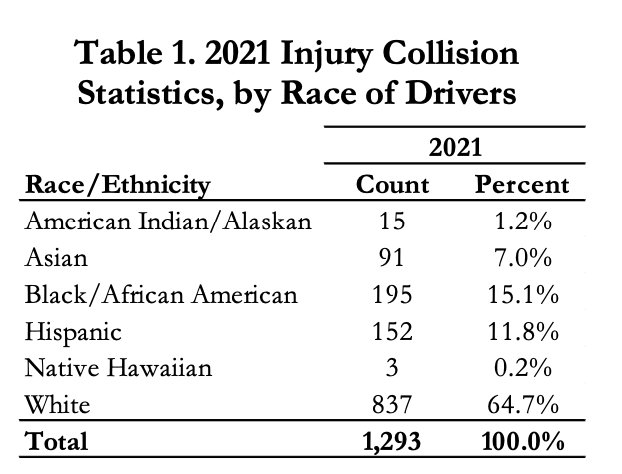

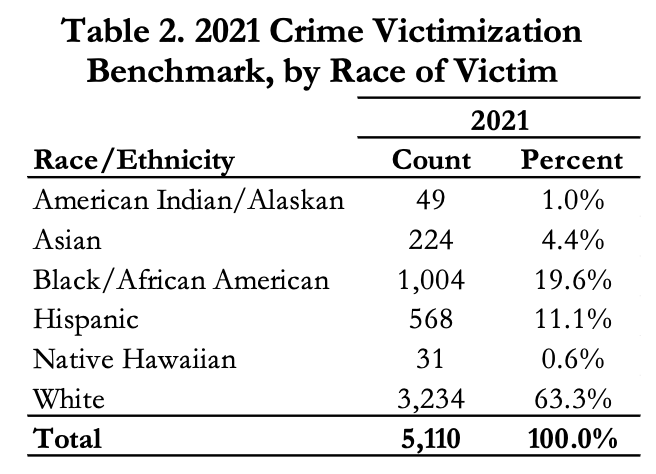

PPB uses injury collision rates – the demographics of people involved in injury collisions investigated by PPB officers – as a benchmark to use when comparing their traffic stop data to the general population. For the Non-Traffic Division, PPB uses the demographics of crime victimization rates as a benchmark. Both of these benchmarks (see charts below) present a far higher percentage of non-white Portlanders than actually live here.

According to their internal data, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander drivers were the only group overrepresented in PPB traffic stops in 2021, and otherwise, PPB officers did not show racial discrimination within their traffic stop procedures. But given the lack of substantial police oversight within the Bureau and its history (and ongoing demonstration) of institutional racism, some people have called this practice into question.

What’s next?

The report states the “slight declines witnessed in Minor Moving Violation and Non-Moving Violation stops” are “an encouraging step and demonstrates the Bureau’s willingness to act and change.” But the racial disparities have not improved, which Lovell himself has acknowledged.

It’s unclear the effect the Wheeler and Lovell’s instructions and the PPB staff shortage had on Portland’s traffic crash fatality rates, which were exceptionally high last year and aren’t too much better this year. Even if PPB officers had directed their attention to the most dangerous offenses, data suggests increased policing doesn’t work as a method of preventing traffic crashes and deaths.

Instead, advocates say infrastructure changes are what’s needed to improve street safety. Some advocates are in favor of solutions like traffic camera speed enforcement, which can now be processed without costly and time-consuming police involvement.

Read the PPB’s full report here.