To Bob Ortblad, a retired civil engineer who lives in Seattle, the team behind the Interstate Bridge Replacement Program (IBRP) – the plan to expand I-5 bridge between Vancouver and Portland across the Columbia River – have it all wrong.

While other advocates have proposed alternatives to the highway expansion, like congestion pricing or a project that better incorporates public transit light light rail or even high speed rail, Ortblad has spent the last three years trying to convince planners to consider scrapping the bridge idea altogether, opting instead for an immersed tube tunnel (ITT).

But he says IBRP planners have tunnel vision when it comes to his immersed tunnel vision.

Ortblad’s case for a tunnel under the Columbia River revolves around safety, land use and environmental impact. He’s written dozens of letters and slideshow presentations explaining his reasoning, but says the IBR program team hasn’t given his idea the serious consideration it deserves.

“The people at the IBRP have been manufacturing consent for this bridge. It’s Kabuki theater.”

— Bob Ortblad, transportation advocate and retired engineer

According to Ortblad, who has been inspired by tunnels around the world, like the Hvalfjörður Tunnel in Iceland, which stretches about three and a half miles under a fjord, the Oresund Bridge & Immersed Tunnel connecting Sweden to Denmark and the Fort McHenry Tunnel carrying traffic on I-95 under the Baltimore Harbor.

As far as safety advantages, Ortblad gives two key considerations. First, bridges can be dangerous for people traveling across them via any means of transportation. In an August letter to the editor of The Columbian, Ortblad referenced the case of Antonio Amaro Lopez, who plunged off the I-205 Glenn Jackson Bridge across the Columbia River on Valentine’s Day last year (and whose family is now suing ODOT for negligence).

Ortblad says the I-205 bridge is dangerous enough, but the new I-5 Columbia River bridge, which has a 4 percent downgrade and shaded northern exposure retaining black ice, will be even more dangerous.

One reason planners cite the need to replace the I-5 bridge is the threat of earthquakes. Other projects are underway to replace bridges in the region for the purpose of earthquake-readiness, like the Earthquake Safe Burnside Bridge project, but Ortblad says a tunnel would be the better way to go for crossing the Columbia.

Some seismically active regions like the San Francisco Bay Area and the entire country of Japan, have implemented immersed tube tunnels which have held up through high-magnitude earthquakes. Ortblad points to the buoyancy of tunnels to explain their seismic resistance. If an earthquake happens, the thinking goes, tunnels are more flexible and can move with the ground instead of being tossed around by the shaking earth.

The ability to preserve land on Hayden Island and Vancouver’s waterfront is another reason Ortblad wants IBRP leaders to consider a tunnel. Replacing the I-5 bridge will require long, elevated concrete viaducts to lift traffic 100 feet or more up to the bridge, taking up a lot of room with on and off-ramps. A graphic Ortblad created (below) warns that leading IBRP designs would “dump acres of concrete on Vancouver’s waterfront.”

That elevation gain has also been raised as a concern for bicycle riders, who’ll have to pedal up it each time they cross the river. “Only the very fittest will be able to climb on a bicycle or on foot the 100-foot ascent (ten stories) needed to cross a new high bridge,” Ortblad shared with us after seeing preliminary bike plan designs from IBRP staff in December. “At age 75 and walking with a cane, you can count me out.”

Comparably, an underwater tunnel would be hidden from view – as would the noise its traffic would generate – and the ground-level entrance would make it easier for people to enter the tunnel. (Ortblad gestures to the Maastunnel in Rotterdam, Netherlands (shown above) as an example of a bikeable immersed tunnel.)

The IBR program team did an analysis of the immersed tunnel alternative and threw cold water on it. Why? According to the IBRP’s memorandum on its evaluation of the immersed tunnel alternative, it has “numerous challenges [which] demonstrate it is not a viable replacement solution for the IBR program.”

Advertisement

The IBRP team even went on the offensive against the tunnel idea on social media last month:

Why isn’t a tunnel a feasible solution for our program?

▪️It would eliminate important connections to Hayden Island, downtown Vancouver and SR-14.

▪️It would cost more than a replacement bridge.

▪️It comes with significantly more environmental impacts. pic.twitter.com/XosegjW6Sq

— IBRprogram (@IbrProgram) January 19, 2022

The stated challenges include “significant out-of-direction travel for drivers, freight, transit users, bicyclists and pedestrians; the inability to tie into existing connections such as SR 14, Vancouver City Center, and Hayden Island; safety concerns for bicyclists and pedestrians; and significant archaeological, cultural, and environmental impacts” as well almost double the cost.

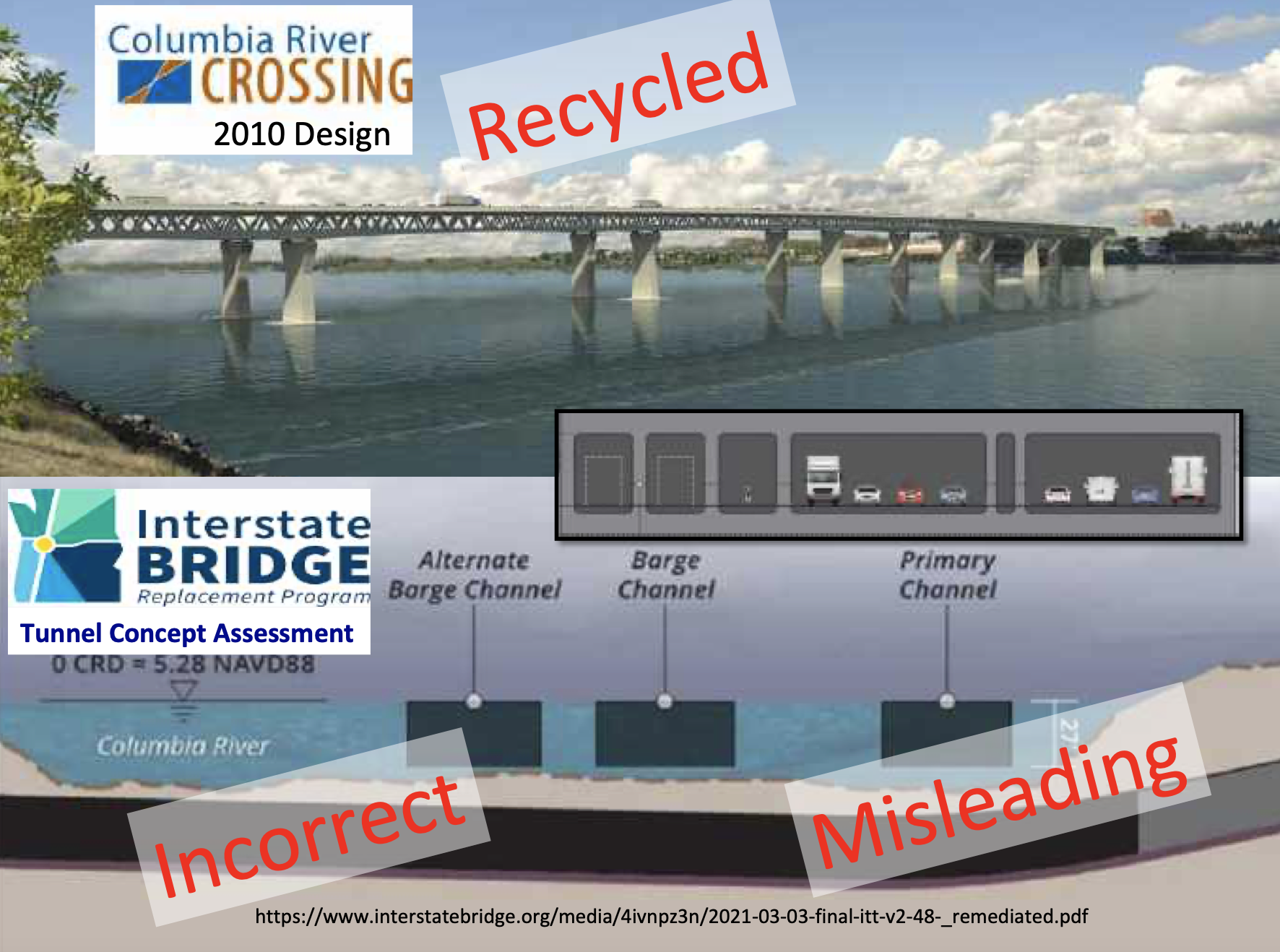

But Ortblad says this analysis wasn’t done in good faith. To him, the IBRP administration is pushing through the 10-year-old CRC bridge design, the previous iteration of an I-5 replacement bridge, under a different name. This project was killed in 2013, which was a relief to environmental and bike activists who had advocated against it.

“The people at the IBRP have been manufacturing consent for this bridge,” Ortblad tells BikePortland. “It’s Kabuki theater.”

In an October letter to the editor at Clark County Today, Ortblad asks for this analysis to be retracted. He says WSP USA, IBRP’s engineering consulting group, has a conflict of interest in evaluating an immersed tube tunnel because it is “anticipating hundreds of millions in bridge design and construction management fees.”

Ortblad says the analysis evaluated an ITT under the current primary barge channel at the bridge lift by the Vancouver riverbank, when it should have evaluated a channel near the center of the river, which would have resulted in a more realistic and inexpensive tunnel design.

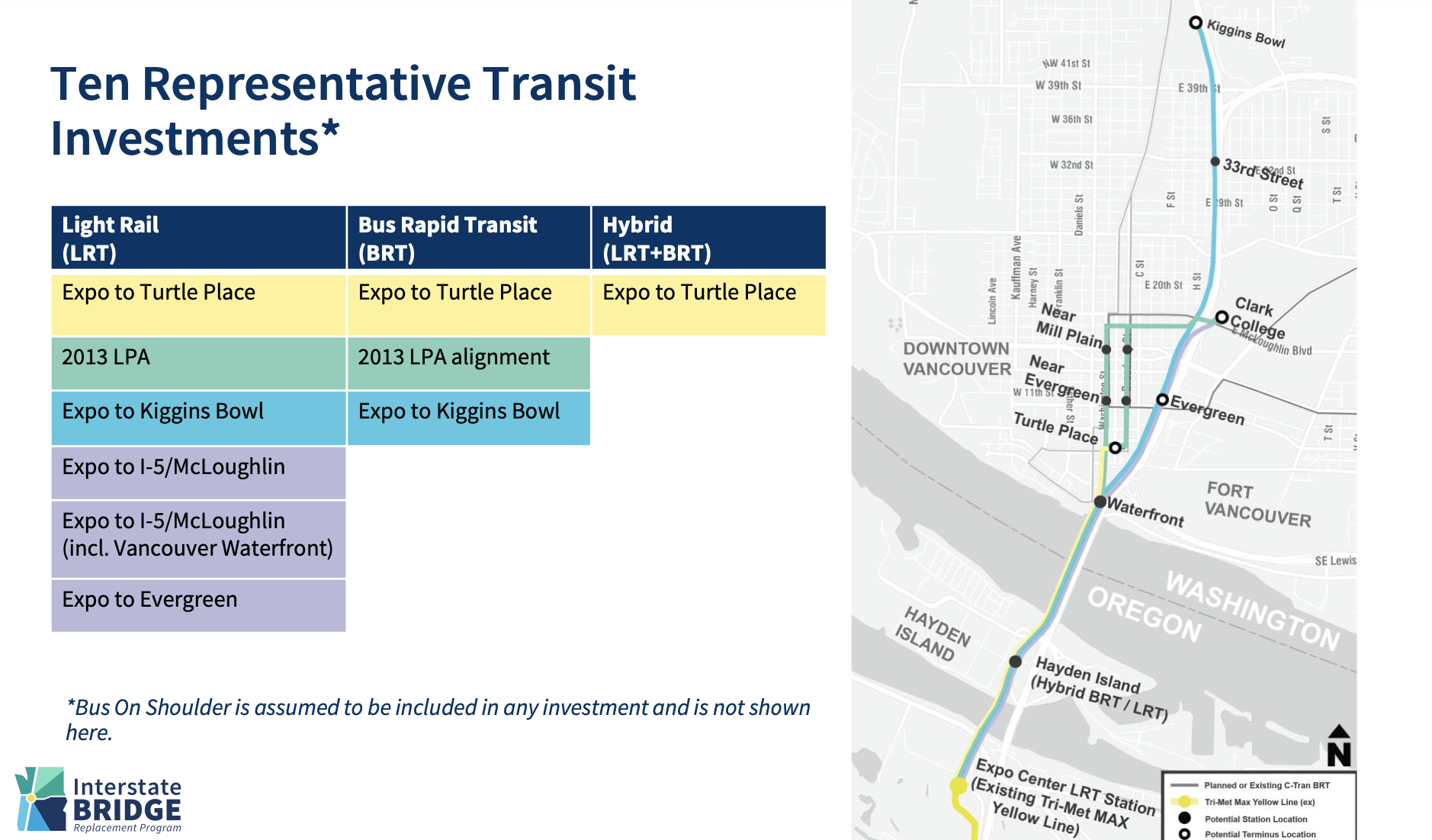

At an IBRP Equity Advisory Group meeting on Monday, project managers showed 10 potential new transit alignments for the bridge, most of which are light rail options. The light rail debate was a big part of the conflict that ultimately doomed the original CRC, so its inclusion is notable.

Ortblad says IBRP leaders haven’t given his tunnel idea the time of day, but he persists anyway, penning letters to politicians and the editors of Portland-Vancouver area newspapers. Having tried relentlessly to get IBRP administration’s attention, he has now moved on to try to get policymakers on board.

“I plan to share my advocacy and research with the United States Coast Guard, U.S. Corps of Engineers, Federal Highway Administration, Federal Transit Administration, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, my elected representatives, community and business associations, and the press,” he wrote in a letter to Washington State Senator Marko Liias in January.

“Going under the river is a better solution than going over.”