(Photo: Jonathan Maus/BikePortland)

Discussions of how gentrification and displacement are tied to transportation is something we’ve covered at length here on BikePortland over the years. But what’s missing from our understanding of these issues are perspectives from Black Portlanders who’ve been directly impacted by being uprooted from their close-in neighborhoods and living in a place that’s far less easy to get around in.

Research just published by former Portland resident Steven Howland gives us new insights about how severe demographic changes in north Portland have taken a toll on Black lives. Howland’s research was done as part of his pursuit of a Ph.D. of Philosophy in Urban Studies from Portland State University. His dissertation, ‘I Should Have Moved Somewhere Else’: The Impacts of Gentrification on Transportation and Social Support for Black Working-Poor Families in Portland, OR, was funded by the National Institute for Transportation and Communities and has been published by the Transportation Research and Education Center at PSU.

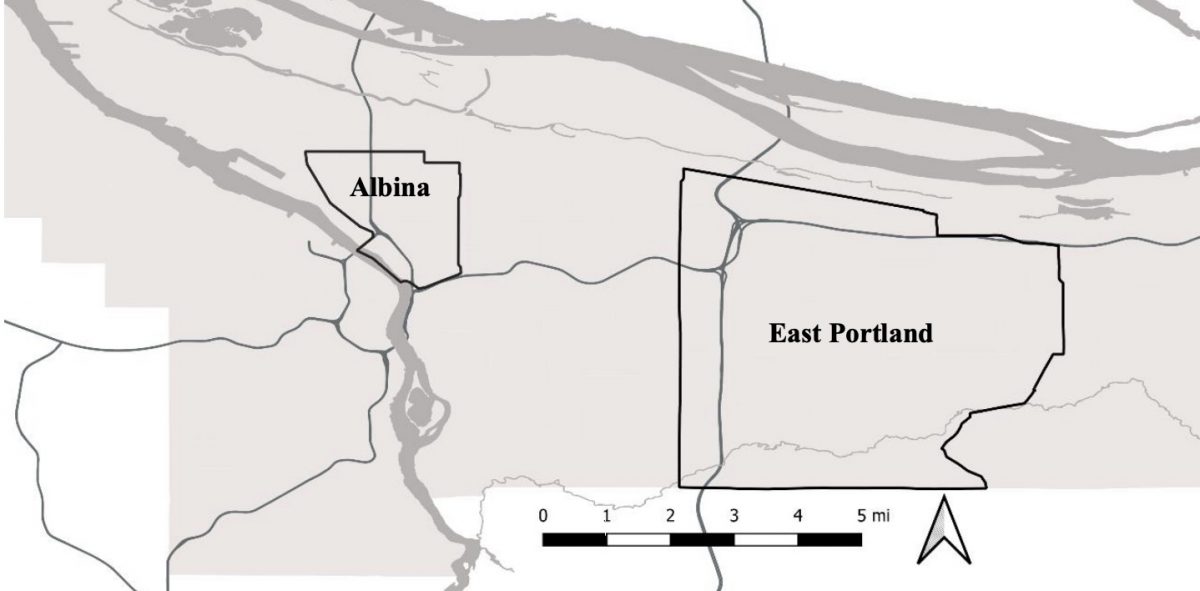

In 2017 Howland interviewed 27 working-age Black people with children — half of them lived in Albina and the other half had moved from there to east Portland. In addition to asking about mode preferences, Howland asked questions about the social impacts of being uprooted from Albina (an older, more dense and walkable neighborhood) to east Portland (a place with more arterial streets, and longer distances between destinations).

What Howland found was striking and should create even more urgency to make transit, walking and biking compete better against driving — and to prevent displacement in the first place.

Howland’s interviews reveal the human side of the challenges people face when they move from close-in to suburban neighborhoods. “I found that people in Albina were better resourced, on average, to accomplish their daily life maintenance,” he wrote. “Through easier transportation (including a higher rate of car ownership), better and stronger social support networks, and a higher density of nearby destinations, Albina residents could get around faster, easier, and accomplish more in a day. East Portlanders struggled far more. Clustering of destinations around the western edge of East Portland put those destinations out of reach for most of them.”

Here’s more from Howland:

“Given the level of disadvantage facing low-income Black populations based on where they can live and the resources available to them, mode choice has a drastic impact on their life outcomes… For low-income Black populations, the effects of racism, segregation, and sustained material hardship prevents their full participation in society. A society, which through suburbanization and orienting life and policy around the automobile assumes people will get around by a car and can travel long distances for their everyday life. They are thereby socially excluded from society, but we have limited knowledge as to the way this manifest in the lives of low-income Black populations or the effects it has on their life.”

Advertisement

Despite strides Portland is making with transit, bicycling and walking infrastructure, they still lag far behind driving in perceptions of safety and desirability.

“We got this busy intersection here and these other cars that be speeding down the damn street, a residential street. They be doing 50 down a 25mph. Don’t ride it out here. I don’t trust it out here.”

— East Portland father

When it comes to using TriMet, many of Howland’s interviewees expressed frustrations with reliability and a fear of other riders: “This was spurred in part by the racially-motivated murders on MAX, but mostly because of their encounters with homeless people and people with untreated mental illnesses which also spilled over into overt racist acts against them or their children.”

His report includes harrowing accounts of walking in east Portland. “Yea, the drivers. You never know with the drivers. Like at night you really need them reflectors, because they drive like crazy down 162nd. It’s bad,” remarked one woman. Another bemoaned the lack of safe crossings: “There’s not that many crosswalks. I’m glad they just made one at 165th where I live. But crossing the street at night, it’s like you either have to walk all the way to 162nd or to 174th to properly cross the street. But I end up crossing the middle of the block. And people aren’t following the speed limits. Or they’re always pulling out the bar drunk or something.”

Despite bad reviews of TriMet and fears around walking, bicycling barely registered as a viable mode among the interviewees. Only three of the 27 people Howland spoke with rode a bike — and none of them did so on streets due to safety concerns.

“I’m not doing that. Sweating. People looking at me, I’m sweating, pedal pedal pedal. You know. Before it gets to that point, I would rather just walk to my destination. Because then I’ll have my purse with me where I’ll have a bottle of water or something. But yea I’m not biking it,” said one woman.

One father he interviewed in east Portland was too afraid to let his kids bike near their home so he’d load them in his truck and only let the kids ride when he visited family in Albina. “Where we stay at it’s real crazy,” the man said. “We tell ’em ride [bikes] at your grandma’s [who lives in

Albina] because the area over there is safer. We got this busy intersection here and these other cars that be speeding down the damn street, a residential street. They be doing 50 down a 25mph. Don’t ride it out here. I don’t trust it out here.”

Howland’s research comes in the same month that Willamette Week reported about how east of 82nd, overcrowded living conditions have contributed to COVID-19 infection spikes and fewer street trees lead to higher summer temperatures.

Whatever we’re doing to improve the lives of people who live in east Portland, we need to do more of it. Faster.

You can follow Howland on Twitter and learn more about this research on TREC’s website.

— Jonathan Maus: (503) 706-8804, @jonathan_maus on Twitter and jonathan@bikeportland.org

— Get our headlines delivered to your inbox.

— Support this independent community media outlet with a one-time contribution or monthly subscription.