(Photo: J. Maus/BikePortland)

Story by BikePortland Contributor Catie Gould

On May 17th, the Portland Bureau of Transportation (PBOT) issued a press release to announce a reconfiguration of SW Madison Street aimed at faster bus service. “The upgrade of SW Madison is the first Central City in Motion project to be implemented, just six months after the plan was passed by Portland City Council,” the press release touted. Five days later it was done.

But for a handful of transportation advocates, the work began two years earlier. Today we’re peeling back the curtain to share what went on behind the scenes.

The summer of 2017 was bad for traffic. From April to October the Morrison Bridge, which carries 50,000 vehicles a day, closed access to downtown through the summer for construction. Less than a week into the closure, the Oregonian reported, “Much of the morning traffic has shifted to the Hawthorne Bridge, which has been clogged from about 7 to 10 [a.m.] for most of the week.”

On May 4th of that year, local lawyer and transportation advocate Alan Kessler posted a video of the backup on Twitter:

It is time for @trimet and @MultCoBridges to open the outer lane on Hawthorne for transit only. This is utterly absurd. pic.twitter.com/sQ8lwqazkb

— Alan Kessler (@alankesslr) May 4, 2017

One week later, BikePortland covered the story and linked to a meet-up of activists who wanted to work on bus priority lanes. That’s how Portland Bus Lane Project started.

By August, Bus Lane Project volunteers were making an official effort to pilot a bus-only lane on SW Madison with another all-volunteer, grassroots group of transportation reformers, Better Block PDX. Better Block works with transportation and planning students at Portland State University (PSU) to develop traffic control plans (required for temporary road closures) and for pop-up projects that are officially permitted by the City of Portland. Better Block are the folks who brought us projects like Better Naito, Better Broadway, and the Ankeny Alley/SW 3rd Plaza project. The program is so well respected at PSU that it was officially added to the curriculum this spring.

The PSU students worked on concepts for SW Madison with Better Block through the winter, and by early April were discussing designs with TriMet and PBOT. On our end, as fledgling all-volunteer groups sometimes go, several people who kicked-off the project had moved on to other jobs or commitments, and we put out an internal call for more help. In the end, there were five volunteers who stepped up to see the project through to the finish line. I was one of them.

“Allowing PBOT to dictate that right turns must be allowed onto 3rd and 1st means we have allowed them to kill the project.”

— Marsha Hanchrow, Portland Bus Lane Project volunteer

The new Bus Lane Project leadership had immediate friction with the proposed design. “Why would we put bikes in between buses and traffic?” I asked at a meeting, worried about the reaction from BikeLoudPDX, another activist group I volunteer with. We sent in three different cross-sections that moved the bikes farther from moving vehicle traffic for consideration.

Routing the bike lane behind the bus stop would be more comfortable for people on bikes, but we had no examples of a temporary bus island small enough to fit that would maintain ADA access. My largest concern however, was that in the middle segment of our project — from SW 5th to SW 1st Avenue — there was a shared right-turn lane for drivers onto SW 3rd Avenue that allowed them to re-enter the protected bike and bus space.

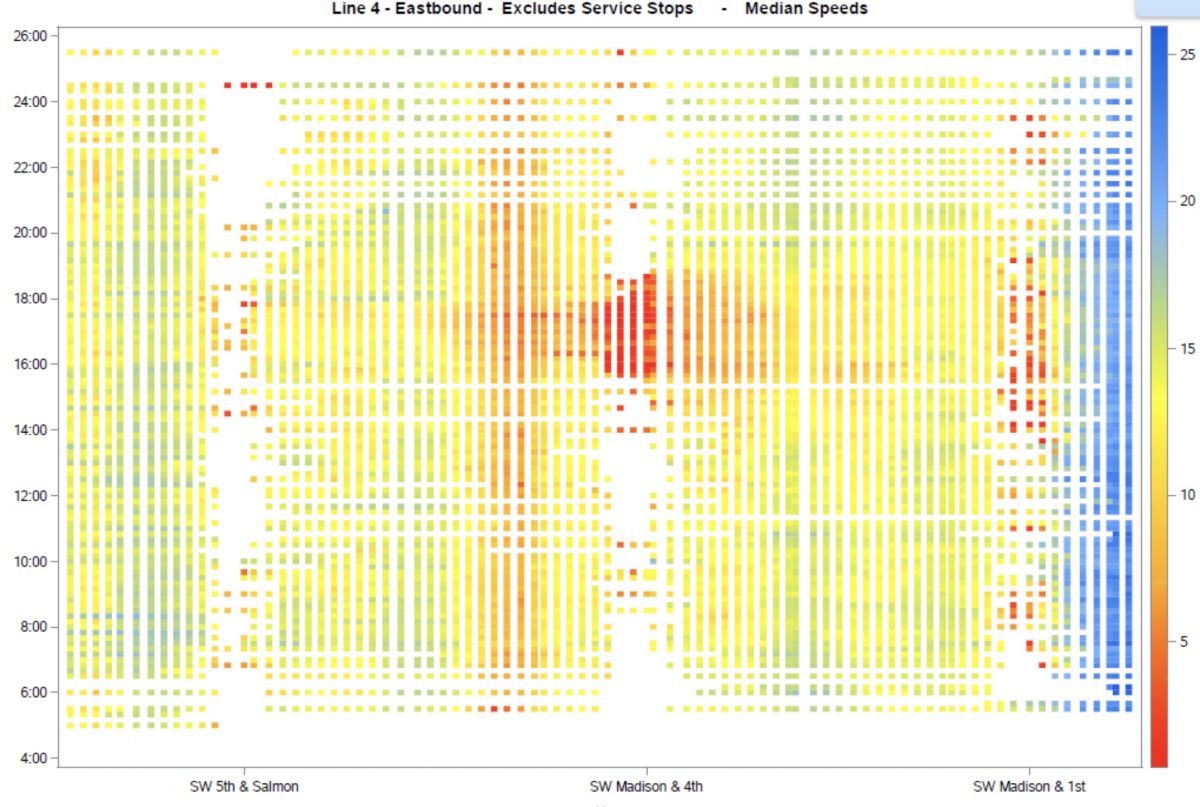

“The more I look at what we’re now presented with, the less I want to be involved,” Bus Lane Project volunteer Marsha Hanchrow wrote via email after seeing the design. “For me, allowing PBOT to dictate that right turns must be allowed onto 3rd and 1st means we have allowed them to kill the project.” We scrambled to find data to bolster our case that shared right-turn lanes would slow the bus down. TriMet data showed backups throughout the day at SW 1st Avenue, which had a shared turn lane.

Advertisement

PBOT didn’t budge on the right turns, citing access to a parking garage nearby as the reason. The death of Kathryn Rickson at the wheels of a right-turning truck driver at this intersection was brought up; but to no avail. This remained a major sticking point throughout the process.

Swapping a general travel lane for a parking lane would give us two extra feet of road space that we could use for a better protected bike lane.

At the same time, we researched bus lane projects in other cities as guides and found one thing in common: city-staffed implementation. Most of our meetings with staff were over the phone, and once written down, our to-do list grew quickly as we e-mailed the rest of the team what was expected of us. As a start, we needed liability insurance, an estimated $10,000 for materials and sign installations, and a commitment for around-the-clock response if something needed attention. “We didn’t have any money as a group at all,” recalled Sam Fader from the Bus Lane Project, “Honestly, I don’t know if anybody knew exactly what was needed, even PBOT. It was kind of new territory for everyone.”

Despite these concerns, we pressed forward and looked for funding. We applied for a community grant, and PBOT offered that it could be funded through an Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT) Traffic Mitigation fund for the I-84 ramp closure in August. “It was a glimmer of hope,” Paul Leitman of the Bus Lane recalled about the funding opportunity.

But even if the funding came through there were still key questions that needed to be answered if we wanted to finalize the implementation plan. Chief among them: the Portland Police Bureau (PPB) had not yet agreed to move their designated parking spaces that spanned from SW 4th to SW 2nd.

After meeting with the PPB to explain the project, they denied our request, so we escalated the issue with PBOT. Our design assumed the police vehicles would be relocated, but we continued to create sketches that included the parking as a backup. Swapping a general travel lane for a parking lane would give us two extra feet of road space that we could use for a better protected bike lane.

Aside from the design, we were being asked to temporarily cover the green bike lanes to prevent confusion. In the past, Better Block had used duct tape to create crosswalk lines, but re-striping an entire lane with heavy bus traffic had never been done before. Chalk paint also had a weather element we weren’t sure how to plan for. A three-day bus lane trial in Boston had used cones, and Toronto’s King Street pilot used jersey barriers to block lanes. Neither of those solutions appealed to PBOT.

The financial and liability requirements required from volunteers severely limits Portland’s ability to do more of them.

We put our concerns about material choices and the right turn on SW 3rd Avenue in writing in early May of 2018. The PSU semester was wrapping up and as the planning students working on the project submitted a final report, our window to change the official traffic control plans to a different design vanished before our eyes. Overwhelmed and unsure of our capacity to pull it off safely, we officially terminated our commitment to implement the project ourselves a few weeks later, still hopeful that the funding would come through for PBOT to do it themselves.

In June we received notice that the ODOT funding didn’t come through, so the project went on the list as one of the possible Central City in Motion (CCIM) projects. We didn’t hear anything else about it until PBOT asked us for a quote for their press release nearly a year later.

“Although Bus Lane and Better Block PDX did not implement Better Madison, it was still a complete success. Those conversations are what led to such a fast implementation,” Ryan Hashagen of Better Block told me over the phone. “You should be taking a victory lap.”

SW Madison still brings up mixed feelings for me. It’s clear these pilots push projects forward before PBOT would otherwise implement them; but the hundreds of hours of time spent collectively between staff and volunteers on these four blocks showed a clear disconnect between our desire to move fast and follow the same design standards as permanent capital projects. The financial and liability requirements required from volunteers severely limits Portland’s ability to do more of them.

That is what makes me so excited for Commissioner Chloe Eudaly’s bus lane projects. With only eighteen months before implementation, it will be necessary for PBOT to evaluate their own processes for how we implement pilots and hopefully set the stage for many more to come.

— Catie Gould

Never miss a story. Sign-up for the daily BP Headlines email.

BikePortland needs your support.