Remember Metro and TriMet’s attempt to build a bus rapid transit line between downtown Portland and Gresham?

Three years ago the agencies embarked on an ambitious plan to route super-fast buses along SE Powell Blvd.

Unfortunately, a reluctance to constrain existing auto capacity on busy 82nd Avenue — a key link in the route — led to projected bus travel times that fell below federal requirements. In other words, their “bus rapid transit” wasn’t rapid enough.

The new plan agreed to by both agencies and a steering committee is to make significant bus upgrades and route a new, “high capacity transit” line on Division Street. If funding plans materialize as expected (they’re hoping to get into President Trump’s infrastructure budget), the $175 million project is scheduled to open in 2021 and will run 14 miles from Northwest Portland to the Gresham Transit Center/Mt. Hood Community College.

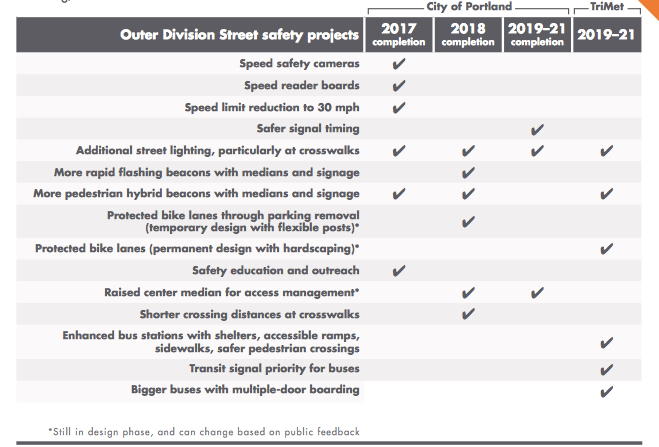

With the route utilizing Division Street, the Portland Bureau of Transportation wants to make sure the transit project maximizes potential of the Outer Division Safety Project, which is the centerpiece of their Vision Zero efforts. PBOT has teamed up with TriMet for the project’s first big open house tomorrow (6/29) Portland Community College Southeast (2305 SE 82nd) from 5:00 to 7:30 pm.

Like PBOT’s plans, TriMet’s project will impact bicycling in several important ways. The agency needs your feedback on new station locations and designs and how best to take bikes on-board the new — and longer — buses planned for the route. Whether you ride bikes, the bus, or both, now is the time to weigh in.

Last week I sat down with TriMet’s Division Transit Project Manager Michael Kiser and Active Transportation Planner Jeffrey Owen to learn more about the project.

Coordination with PBOT

TriMet’s Kiser says his project will “clarify the corridor” and create a better place for PBOT to insert its updates to Outer Division. “We will build off the approach they’ve defined,” he said.

For instance, PBOT’s plans call for protected bike lanes on Division from 82nd to the eastern city limits (164th or so). The city aims to complete these lanes with a temporary design using plastic “flexible posts” by the end of 2018. Then TriMet will come along and make the protected bike lanes permanent by 2021. Kiser said the TriMet project will include funding for real, physically protected (not just flex posts!) bike lanes “as a condition of project approval.”

Similar to the Orange Line MAX project, this transit investment will attract all sorts of attention in terms of planning and financial resources. At this relatively early stage in the design (plans are at 15 percent now and public feedback will help inform 30 percent plans), now is the time make sure current and future bikeways are smartly integrated.

Why not use Hawthorne instead of Tilikum?

The chosen alignment has raised eyebrows because it must cross the Union Pacific Railroad line at SE 8th Avenue. Some people hoped it would use Hawthorne instead due to fears about long railroad crossing wait times. TriMet prefers the Tilikum/SE 8th alignment for reliability (see below) and its stronger connections to OHSU and South Waterfront.

Kiser said Hawthorne was analyzed as a potential option, but was ultimately thrown out because projections showed it gets too clogged with auto traffic too often. TriMet also analyzed UPRR rail crossings and found that “incidents” (crossings) during AM and PM peak times are “pretty minor” and infrequent. “That gave us comfort about the risk of using the Tilikum route,” Kiser said. The assumption from TriMet is that wait times during morning and evening rush-hour would be less than three minutes.

TriMet says they’re also working with UPRR to speed up trains through the area. One method would be to install automatic train switches in the Brooklyn yard to replace manual onces currently in use.

Station designs and locations

With 41 stations and 80 platforms, the new Division transit line will significantly change the look and feel of the street.

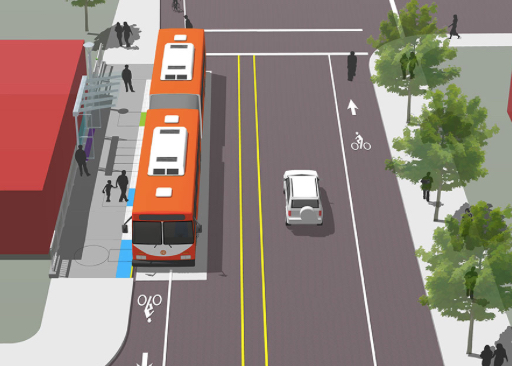

TriMet will use four types of station designs along the route, depending on right-of-way and traffic volume restrictions. Here are the three designs:

Advertisement

Integrated 1:

Integrated 2:

Learn more about each design at the online open house.

Space for faster buses

None of this works if buses can’t go fast. And absent real, 100 percent bus-only lanes for the entire route, TriMet has devised several ways to increase bus speeds.

“Sometimes this project has exclusive right-of-way,” Kiser said, “But for the most part we’re operating within existing travel lanes.”

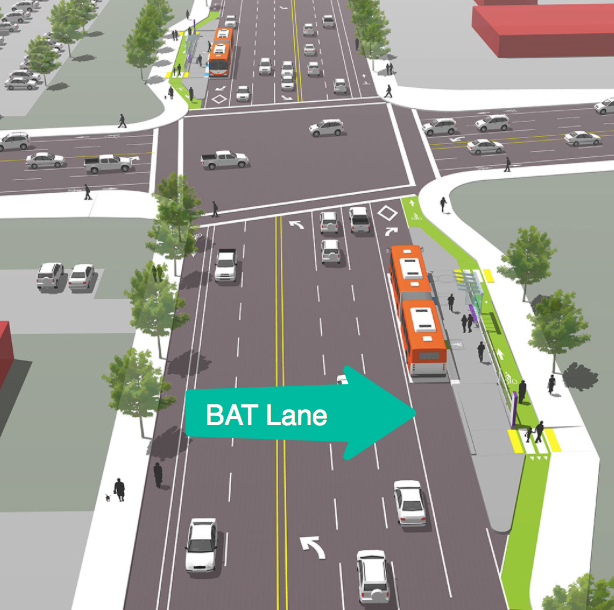

To keep buses moving quickly, TriMet is laser-focused on decreasing “dwell times” (when the bus is stopped for passenger loading) and using a combination of “bus access and transit” (BAT) lanes and high-tech traffic signals to clear cars out of the way.

There will be no more fare-checking by drivers (it will be more like getting on MAX light rail). Station platforms will be raised up so buses don’t have to kneel down for customers. The Hop Fastpass will be operational by the line’s opening day. The buses will have three boarding doors.

And about those BAT lanes: Some of the stations will have specially marked lanes where only buses and right-turning cars are allowed. To keep cars from blocking buses, new signals will be installed to give buses priority. “We’ll be implementing advanced technology for transit signal priority,” Kiser said. “Using systems we don’t even have in place today.”

The signals will be programmed to “flush” cars through the right-turn only BAT lanes so that approaching buses can access stops. TriMet’s Owen said, “It’s an invisible priority that will allow us to sneak through.”

Getting bikes on board (no more front racks!)

One of the biggest changes coming with this project are longer buses. They’ll be 60-feet long, 20-feet longer than typical TriMet buses. And they’ll have three doors instead of two. TriMet’s bike planner Jeff Owen says, “They’re kind of like a standard bus with half another bus attached to it.”

The upshot for bicycle users is threefold; room for more bikes, a bike-specific loading door, and the ability to store bikes on racks inside the bus instead of on exterior front racks.

TriMet says putting bikes inside the bus is meant to improve loading speeds. It’s a bonus that people won’t have to mess with those front racks — which take longer and are intimidating for many people to use.

As for the type of rack that will be in the new buses, that’s still undecided. Based on what other cities are using, TriMet’s Owen says the racks will either be a hook on the roof (similar to MAX) or more of a ramp-style.

If you’d rather park your bike, TriMet plans to install bike parking staples at the new stations. Because this project has a limited budget and existing right-of-way is so constrained, they won’t build new bike parking shelters or bike-and-rides.

As you can see, there’s a lot to consider here. While it won’t be the full-fledged bus rapid transit we need; it will be TriMet’s first-ever high capacity bus line.

“We’re introducing a new type of mode,” Kiser shared with me last week. “We want it to be successful not just for this project but for future projects. We have to set our priorities accordingly, creating that balance between community needs, performance, and costs — and doing it in a way that is transportation and has integrity and equity built into it.”

How does it look to you? Is TriMet Please attend Thursday night’s open house and/or check out TriMet’s online open house.

— Jonathan Maus: (503) 706-8804, @jonathan_maus on Twitter and jonathan@bikeportland.org

BikePortland is supported by the community (that means you!). Please become a subscriber, advertise with us, or make a donation today.