(Image: Google Street View)

Buried inside 115 pages of analysis of Barbur Boulevard, a “safety audit” released Monday seems to have come up with something interesting: a pretty solid new idea for fixing the dangerous wooded section of Southwest Portland’s most important street.

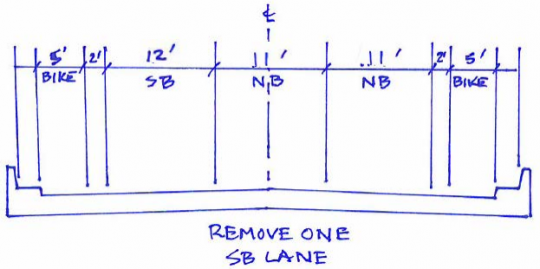

It’s fairly simple. Instead of losing a northbound auto lane from Miles to Hamilton, one of Barbur’s two southbound auto lanes could peel off at Capitol Highway.

South of Capitol Highway — which is where 40 to 50 percent of southbound Barbur traffic exits anyway — the street could be restriped to add continuous bike lanes across a pair of narrow bridges, ending the current situation that pushes bikes and cars to merge into the same 45-mph lane.

This was one of seven scenarios highlighted in the road safety audit commissioned by the Oregon Department of Transportation that we covered yesterday, but it wasn’t until we called around to several of the engineers behind the audit that we started to realize how much the “southbound drop lane,” also known as “Option #5”, stood out.

“It felt like southbound made the most sense, because a lot of the traffic was getting over to the right lane,” said Carol Cartwright, an ODOT roadway manager on the audit committee.

Here’s what the southbound drop lane concept has going for it:

It’d make driving much safer on the most dangerous stretch of Barbur

(Image: Google Street View.)

It’s a myth that the Barbur Woods safety problems are all about people biking. They’re mostly about people driving.

In part because so few people are currently willing to bike on this stretch of Barbur, no one has actually died while biking there. The people who have been dying on Barbur have been in cars or (in two cases) on a motorcycle.

Removing one of the two southbound auto lanes south of Capitol Highway addresses the single biggest safety problem on the wooded stretch of Barbur: extreme speeding by people driving southbound south of Capitol Highway, toward Burlingame and Hillsdale. At least five of the 10 people who’ve died on this stretch of Barbur over the last 10 years were in this situation.

The safety benefits of going from two auto lanes in the same direction to one are well-documented, but mostly boil down to the fact that with only one lane, the most reckless drivers aren’t tempted to weave through traffic. Last year, an ODOT construction project took Barbur down to one lane in each direction. That led to about one minute of additional rush-hour travel delay, but a 68 percent drop in extreme speeding.

That’s no coincidence. The Federal Highway Administration says that restriping streets to remove traffic weaving reduces collisions by 19 to 47 percent.

It might have even less impact on congestion than removing a northbound auto lane

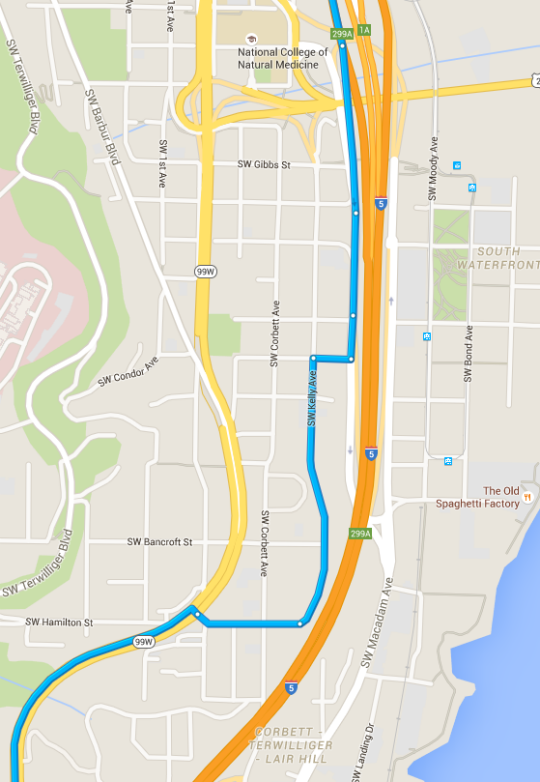

(Image: Portland State University PORTAL system)

The biggest misconception about Barbur Boulevard — the fundamental thing that’s been holding improvements back for years — is the understandable but false assumption that removing one of two auto lanes means a street can only carry half as much traffic.

That’s mostly true on a freeway, but Barbur isn’t a freeway. It has stoplights. As long as the traffic signals on each end of the Barbur Woods are letting through approximately the same number of people on each green light, it doesn’t matter much how many lanes the street has in between.

That said, there’s one big intersection right in the middle of the Barbur Woods: Capitol Highway curls west towards Hillsdale. During the morning rush hour, 50 percent of the southbound traffic peels off there. During the evening rush hour, it’s 40 percent.

If about half of the southbound traffic vanishes south of Capitol Highway, what’s the point of the second traffic lane?

Advertisement

It’d fix one of the worst gaps in the region’s biking network

Carved out for a 19th-century rail line, Barbur Boulevard is the only flat connection between Southwest Portland and most of the rest of the city. Forcing bikes and cars to merge into the same 45 mph lane isn’t just nerve-racking for people driving, it’s a dealbreaker for almost anyone who might be interested in biking.

When Barbur crosses the two bridges just south of Capitol Highway, its lanes are 11.5 to 12.5 feet wide.

If that were switched to two 11-foot northbound auto lanes and one 12-foot southbound auto lane, there’d be room for comfortable buffered bike lanes on both sides of each bridge.

What’s more, there’s room on the rest of Barbur to narrow the travel lanes a bit and add a painted buffer (or even some sort of thin physical barrier, such as flexposts) that could turn this into a genuinely nice route between the densest parts of Southwest Portland and downtown.

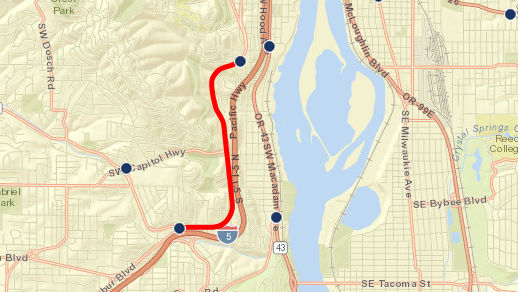

It responds to one of ODOT’s main concerns: Spillover from I-5

Over the last few years, the Oregon Department of Transportation has said over and over again that Barbur Boulevard plays an important role as an escape valve for traffic when trouble hits Interstate 5.

Whatever you think of that theory, here’s something indisputable: this doesn’t apply nearly as much in the southbound direction. Unlike northbound I-5 traffic, which has a relatively intuitive spot to jump onto northbound Barbur five miles to the south, traffic that’s southbound on I-5 can’t get onto Barbur without a zigzag through narrow streets in this Lair Hill neighborhood:

“Accessing Barbur Boulevard from I-5 southbound is challenging and may only attract motorists already in downtown Portland,” the safety audit writes.

Dropping the southbound lane at Capitol Highway would still have challenges

(Photo: M.Andersen)

Like all the options explored in Monday’s safety audit, Option 5 has downsides.

There’s a bus stop at Southwest Barbur and Parkhill that, as of 2012, sees two people get off (and zero people board) on the average weekday. If TriMet buses continue to stop there, they might or might not be able to pull fully out of the way of a single southbound travel lane. There’s another bus stop 2,000 feet north, beneath the Capitol Highway overpass, that sees one person get off per weekday and would also be affected. (Last spring, The Oregonian enshrined that one in video as maybe the worst bus stop in the city.)

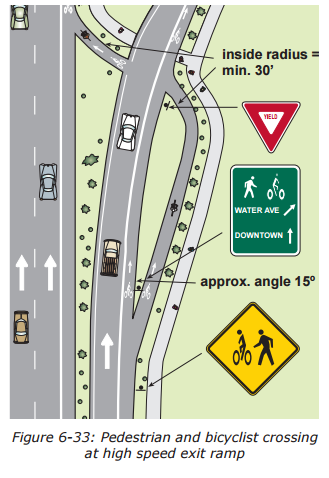

Another complication is that southbound bike traffic would somehow need to cross the drop lane at Capitol Highway. If it’s restriped into a drop lane, it might feel even more like an offramp than it already does.

Depending on how the turn lane works, there might be enough room here in the existing roadway to swoop the bike lane around and create a less acute angle for bikes to cross the ramp. Here’s an image in ODOT’s bikeway design guide that suggests the geometry involved:

On the other hand, one of the main problems with this intersection is that so many cars fail to signal their right turns, so it’s impossible to know, while biking, whether a car is about to zoom up Capitol Highway or zoom under Capitol Highway. If the right lane were a drop lane, someone biking or walking here would know that every car in the right lane was preparing for a turn.

In any case, it’s clear that a bit more design work would be required to know whether this might be an adequate compromise. On Monday, ODOT spokesman Don Hamilton said that ODOT’s Portland regional manager, Rian Windsheimer, will make the call about whether to assign anyone to look at it and at the other options explored here.

“We’ve already decided this requires further study,” Hamilton said. “That’s going to begin soon. … It’s a question of how and when.”

Everyone who drives, bikes or walks on Barbur should hope that work doesn’t wait until after another person dies.

— Michael Andersen

(503) 333-7824

michael@bikeportland.org

@andersem