The Portland City Council is poised to pass a new freight master plan at their meeting Wednesday — a step that comes more than three years after the Portland Bureau of Transportation launched the effort. The new plan, 2040 Freight, will update the existing plan that council adopted in 2006.

We watch freight advocacy and planning closely because of the very tragic record of cycling deaths that have involved trucks and their drivers — as we saw most recently last October when Sarah Pliner was killed in a collision with a semi-truck while trying to cross Southeast Powell at 26th. Portland’s freight advocates have also influenced many bike infrastructure projects over the years. It was taxes paid by truck companies that helped get the separated bike path on North Greeley Avenue built, and it was the Portland Freight Committee (PFC) that opposed the addition of bike lanes to North Lombard (thankfully they got put in anyways).

With the 2040 Freight Plan, the Portland Bureau of Transportation will have an updated guide to manage the freight system and a good opportunity to refresh its freight committee. Unlike PBOT’s bicycle and pedestrian advisory committees, members of the PFC have been able to far exceed term limits. In 2017, in an effort to rebalance and diversify all of its advisory committees, the City of Portland set new term limit rules for advisory committees. This led to several senior members of the Bicycle Advisory Committee having to leave against their will. But when some veteran PFC members pushed back on the new rule, former PBOT Commissioner Chloe Eudaly gave them a special dispensation: They could remain on the committee in order to develop the 2040 Freight plan. Now that it’s completed, it will be interesting to see whether current PBOT Commissioner Mingus Mapps follows through with city policy and makes the PFC recruit over a dozen new members.

It is patently unfair to require the bicycle and pedestrian committees to welcome new members while allowing the freight committee to retain veterans. This has given freight interests a major advantage when it comes to influencing PBOT policies and projects.

Thanks for indulging that little digression… let’s get back to the 2040 Freight plan.

Like other modal plans, PBOT is required by law to have one on the books. The plan does several things: it lays out a framework for making policy and project design decisions, it helps PBOT compete for grants (being able to say, “Xyz project is in our freight plan” helps a project score better), it includes a prioritized list of infrastructure projects, sets freight-related street classifications, and helps give city planners and advocates a deeper context for how the movement of freight fits into the transportation system.

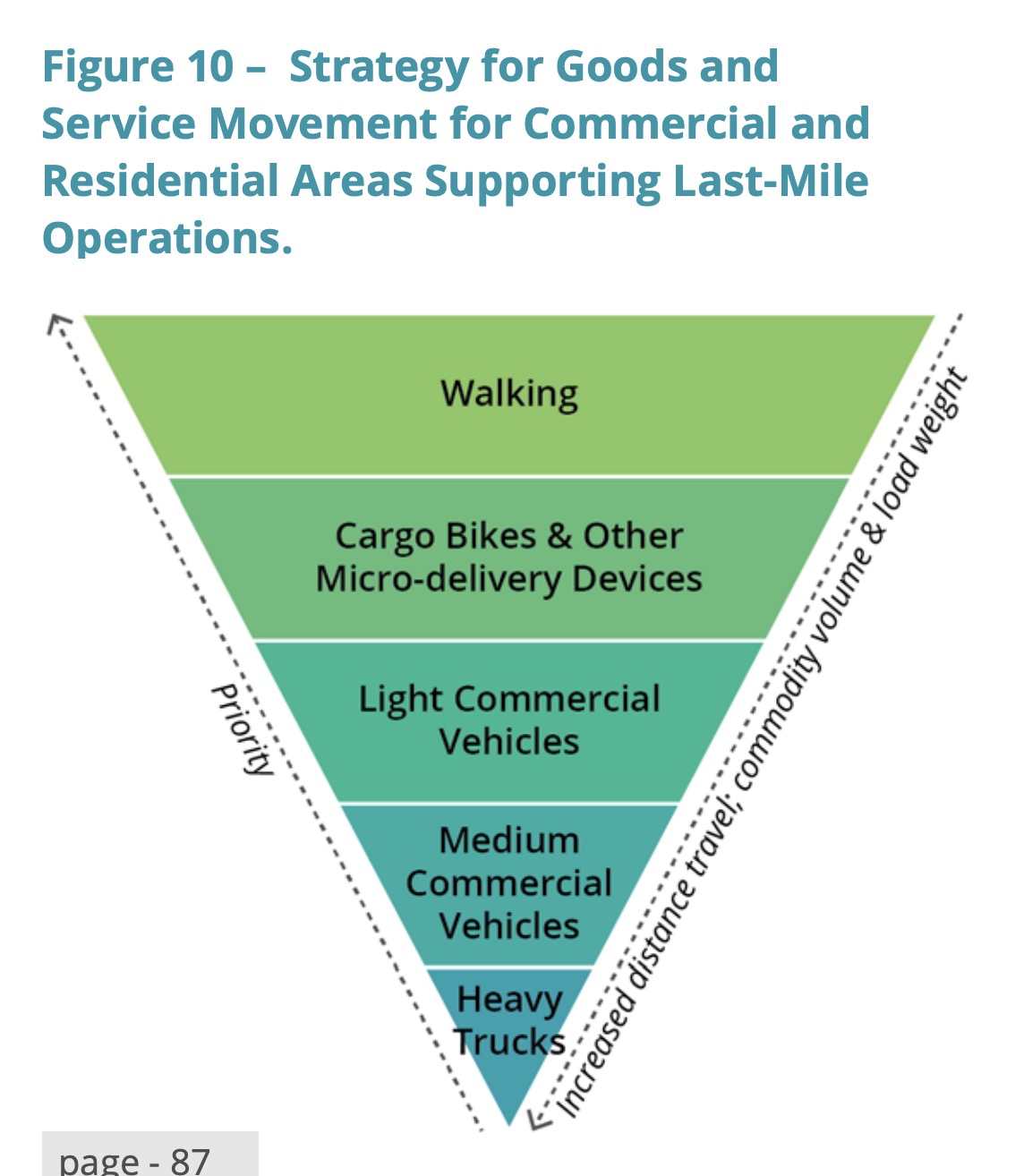

Part of the new freight plan looks to correct past mistakes in how we understand its role. Instead of seeing “freight” as large trucks and a mode of travel alongside “bicycle,” “pedestrian,” and “single occupancy motor vehicle,” PBOT says that framing “fundamentally mischaracterizes it as a mode.” Instead, PBOT sees freight as a system where many different modes work together.

For instance, if the distance is short and the package is light, PBOT says the best freight vehicle would be feet (see graphic at right). For slightly longer trips and heavier packages, an electric bicycle might be the recommended vehicle.

A key takeaway from 2040 Freight is that PBOT wants to get smarter about how the land use and urban design context dictates freight movement.

Right now, the balance is off. Currently the plan states that about 75% of freight movement in the Portland metro area relies on trucks. That means the negative impacts of those trucks — diesel emissions, noise, traffic safety concerns, etc. — has significant impact on our roads and residents. And Multnomah County research shows neighborhoods with a majority of Black, Indigenous and other people of color are exposed to those externalities at two-to-three times the rate of the average Portland-area resident.

And with heavy trucks accounting for about 15% of the total diesel emissions in Portland, you can see why PBOT wants to make freight movement cleaner. Their downtown zero emissions delivery zone is one step they’ve already taken. A different mix of delivery vehicle types will also help.

Smaller and cleaner vehicles will not just help with air quality, they will also free up valuable space at the curb and other congested areas as well as reduce injuries and deaths from traffic collisions.

In the safety section of the plan, PBOT says most freight truck collisions happen at intersections, therefore, “Implementing safety countermeasures for vulnerable users, such as separated facilities for bicyclists, clear signage, or providing for alternate parallel routes will improve safety…”

The plan should help spur more physically separated cycling infrastructure. In a section that defines the “Industrial Roads” street classification, PBOT states, “Pedestrian and bicycle crossings should be grade-separated or signalized, and pedestrian and bicycle facilities should be separated from motor vehicle traffic.”

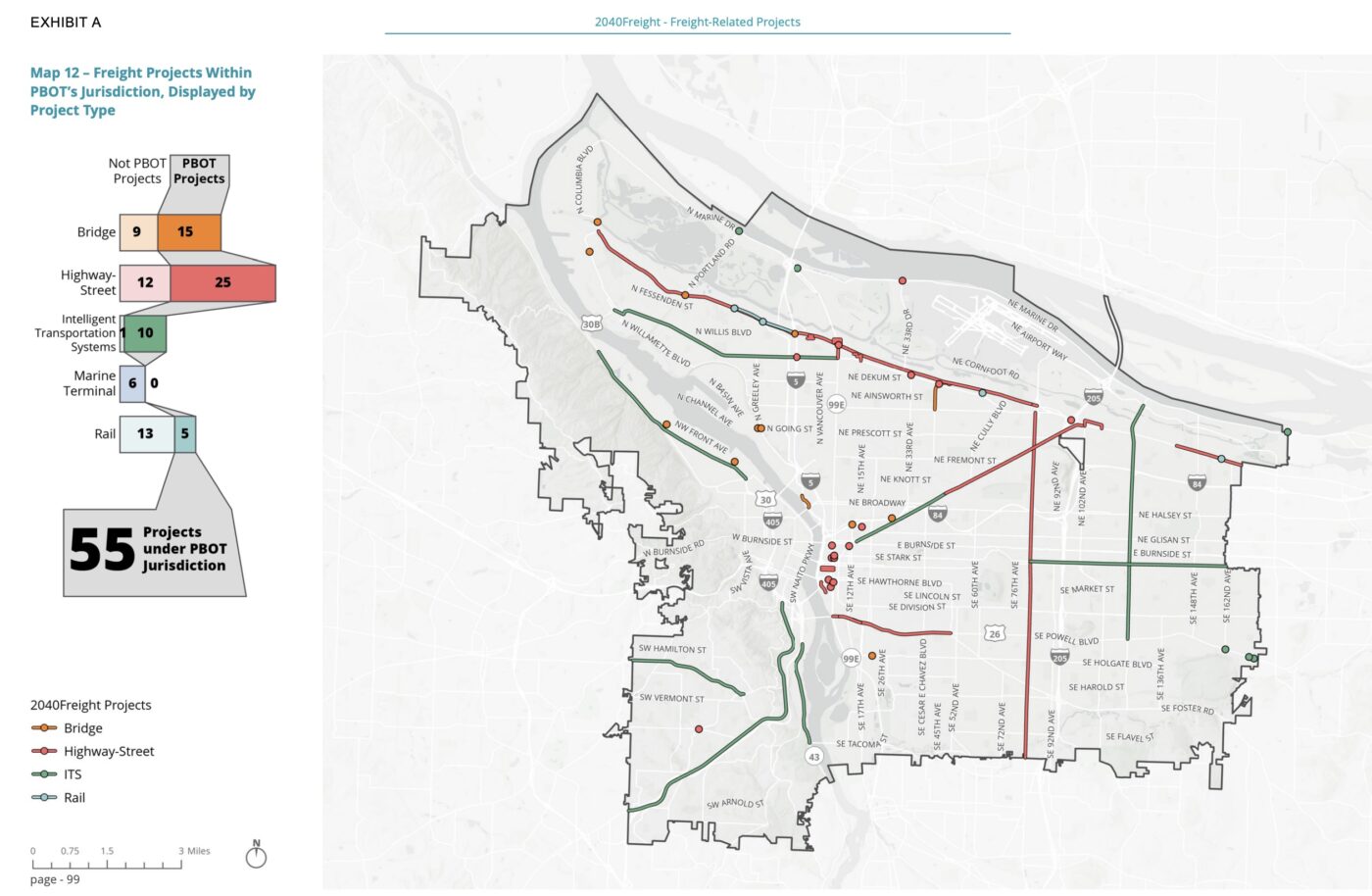

One of the most important parts of the plan is the list of projects. There are 55 projects in the plan worth over $812 million — 14 of which ($265 million worth) are identified as “high priority.” (Note: The plan does not allocate any money to these projects. It is just a list of estimates for planning purposes)

Most of the high priority bridge and highway projects in the plan are located along Columbia Blvd. Two projects totaling $14.5 million along the popular NE 33rd Avenue bike route would include cycling safety updates at Lombard and Marine Drive.

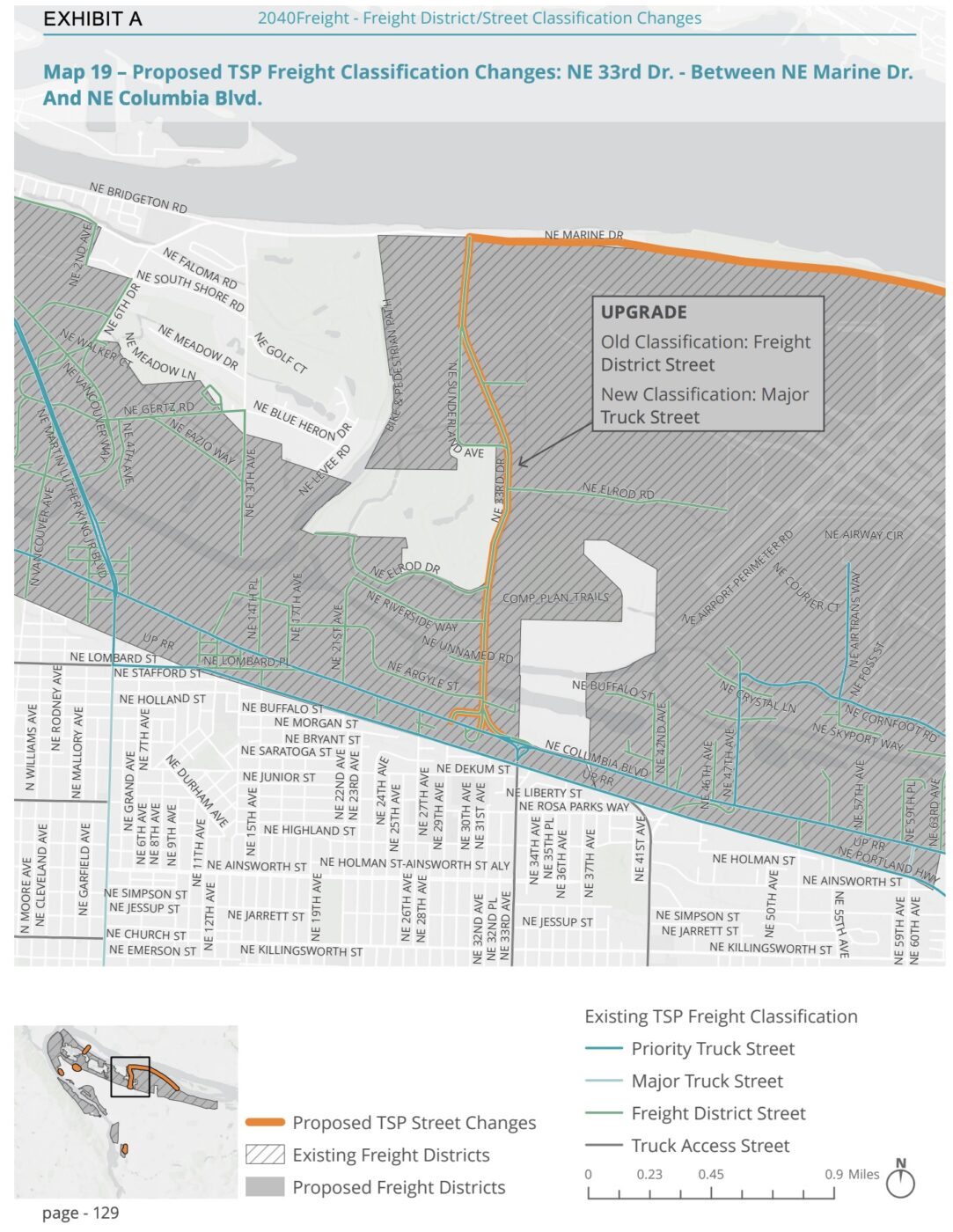

Also notable is that both 33rd Ave (between Columbia and Marine Drive) and Marine Drive (between 33rd and I-205) will be changed to a higher freight street classification in the Transportation System Plan (TSP). These classifications are very important because they dictate what type of cross-sections and design treatments are feasible.

This section of NE 33rd will become a “Major Truck Street” in order to, “recognize the importance of this street for freight movement flow in/out of key origins/destinations within the Freight District.” And Marine Dr will go from Local Service Truck Street to Freight District Street.

These changes reflect PBOT’s desire to “unlock” adjacent industrial areas and make them more freight-friendly. Will it come at the expense of safe cycling infrastructure? That remains to be seen, but it certainly gives freight advocates a leg up in future debates.

Several other projects and policies in the plan have significant cycling impacts. We’ll be covering them as they develop in the months and years to come.

City Council will take up the resolution to adopt the plan at their meeting on Wednesday July 12th at 2:00 pm.

— 2040 Freight on Portland.gov.

.