“They claim to be making progress in reducing emissions, which sends a powerful message to policymakers that we don’t need to do more and we can take our time.”

– Bob Cortright, 350 Salem

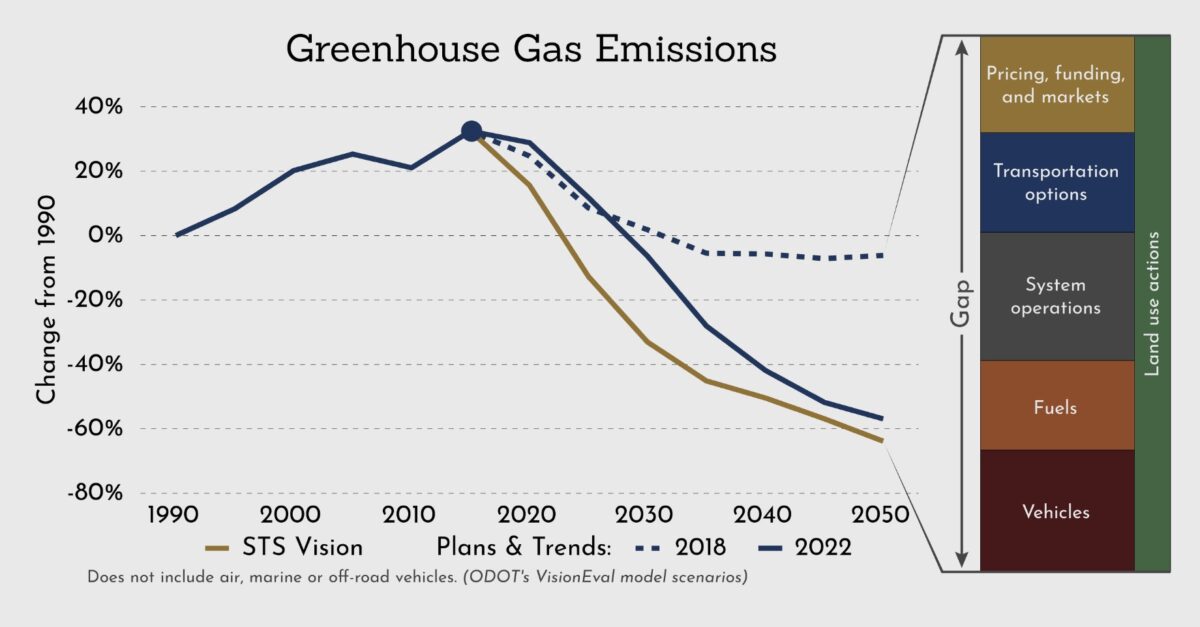

Five years ago, the Oregon Department of Transportation did not have reason to be hopeful about meeting their greenhouse gas emissions reduction goals. ODOT’s 2013 Oregon Statewide Transportation Strategy (STS) calls for the agency to reduce transportation greenhouse gas emissions 80% by 2050 (compared to 1990 numbers), but a 2018 monitoring report (PDF) said emissions were only projected to fall 20% by 2050. And in 2020, the leader of ODOT’s (newly formed) Climate Office said, “We’re heading in the complete wrong direction,” when it comes to carbon emission reductions.

Fast forward to 2023 and the climate crisis is more dire than ever. The most recent report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), released earlier this week, made it clear that time is running out to avoid climate catastrophe. But over at ODOT headquarters, the mood is more optimistic. According to a new website unveiled March 9th, the state is on track to reduce emissions 60% by 2050, which is “short of the 80% goal, but still a dramatic improvement from 2018 projections.”

Great! Now we can just sit back and relax, right? Not so fast.

A closer look at assertions made on the website casts doubt on that rosy picture. Advocates are not only skeptical of how ODOT frames their emissions efforts — they worry the website and PR push behind it could placate policymakers and the public into a false sense of progress.

What’s on the website?

The website is a dashboard detailing ODOT’s progress toward its overall goal of reducing emissions by 80% by 2050 (see chart). ODOT outlines two objectives for this goal: reduce growth in vehicle miles traveled by using “land use laws, incentives and policies to support reductions in the number of driving trips people take and how far they drive each trip”, and clean up each vehicle mile with “new technology to reduce emissions via the kinds of vehicles people drive, such as electric, and the kinds of fuels used to power those vehicles.”

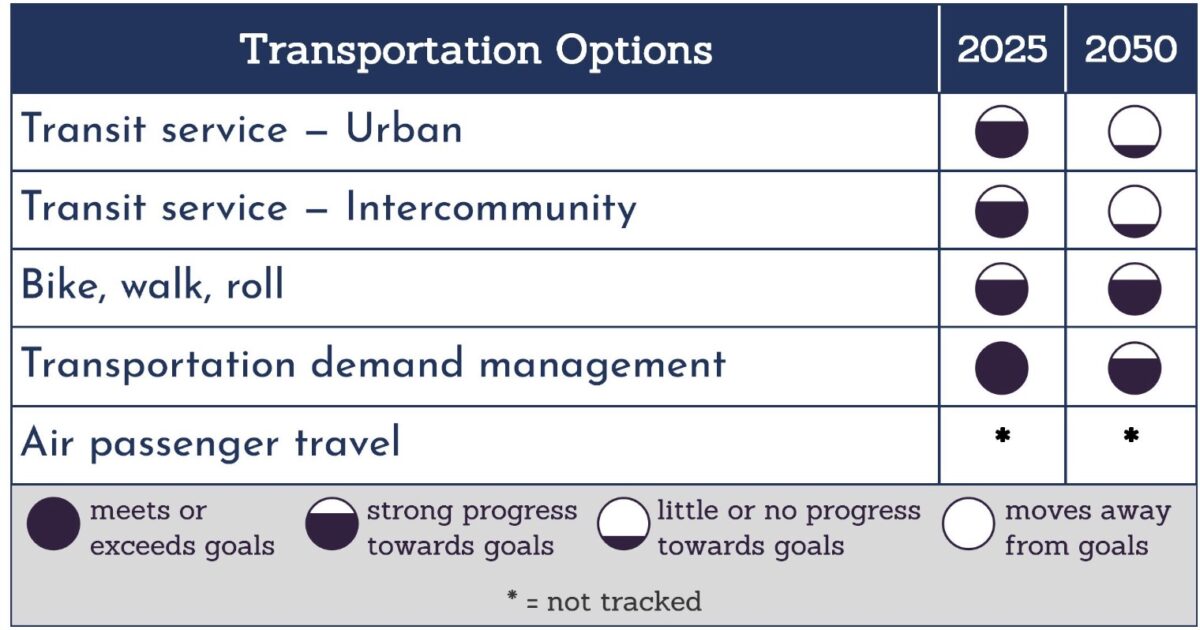

In order to meet these objectives, ODOT has split their actions into six categories: transportation options (which concerns public transportation, biking, walking and rolling and transportation demand management strategies); pricing, funding and markets; vehicle technology; land use; system operations and fuel technology.

It all sounds good, but some agency watchdogs don’t think the new website provides sufficient information to back their claims.

An analysis of the website on Salem bike news blog Salem Breakfast on Bikes calls it “unconvincing…propaganda more than sober analysis, a bit of a slick farrago.”

“The structure is designed to look informative, but in fact it obfuscates. If the progress were truly so great, the structure would be more transparent and easier to parse,” the Breakfast on Bikes article states. “More specifically, it lacks any detailed discussion of what changed between the 2018 forecast and 2022 forecast.”

Salem-based transportation and climate advocate Bob Cortright (twin brother of No More Freeways co-founder and City Observatory writer Joe Cortright) also has some qualms. He reached out to ODOT staff about his concerns, writing in an email to several staff members that he was “troubled by the absence of analysis to support the broad claims about progress” on the website.

“While [the website] is very good at providing a high level description of the broad range programs and efforts to reduce emissions I do not see links to the detailed analysis that supports the conclusion in the press release,” Cortright wrote.

Suzanne Carlson, who leads ODOT’s climate office, responded to Cortright’s email last week. She said the team is “working on some updates to how information is displayed in the website to better highlight the key assumptions and inputs,” which they expect to have ready soon. In an email to BikePortland yesterday, ODOT Public Affairs Specialist Matt Noble said ODOT is working on a new webpage for the site that should be made public during the first half of April.

“The new page will give more insight into our progress since 2018, and what changed to allow for the 60% forecast emissions reduction. We’ll handle requests for deeper data dives on a case by case basis, as that level of detail is beyond the scope of the site,” Noble said.

Without this information, Cortright said the website seems to present a dubious conclusion that could cause people to rest on their laurels.

“They claim to be making progress in reducing emissions, which sends a powerful message to policymakers that we don’t need to do more and we can take our time,” Cortright told me. “It sends a message that we’ve done something in the last five years to turn this around…there are lots of reasons to be skeptical of that conclusion.”

Active transportation stats

The website features a page analyzing Oregon’s progress toward the state’s active transportation goals.

“Transportation options create opportunities for Oregonians to use active modes of transportation on Oregon’s system. Especially ones that emit less greenhouse gas emissions like biking, walking, rolling, scooters, carpooling, public transit, and passenger rail,” the website states.

Here is the vision ODOT has for what active transportation will look like in Oregon in 2030:

- By 2050, 30% of short trips (under 20 miles) in urban areas will be made via biking, walking or rolling.

- By 2050, a majority of urban households have equitable access to biking, walking, and rolling options close to their home.

- The Oregon Department of Transportation continues to provide and expand dedicated and reliable funding for bike and pedestrian infrastructure through 2050.

Sounds pretty good — how are we going to get there?

Apparently, we’re not so far from meeting the first goal as it might seem: ODOT claims that 12% of Oregonians travel by walking, biking or rolling, citing the Oregon Household Survey conducted from 2009-2011. (The survey they linked to actually said the number was 11%). Even better: they said this number has grown during the pandemic. But when BikePortland tried to find a source for this statistic, it was nowhere to be found. When BikePortland reached out to ODOT for more information about this, they walked back that claim.

“Some data we looked at suggested this, but on further scrutiny, we’re going to remove that line from the site until we have more data certainty,” Noble wrote.

When BikePortland tried to find a source for this statistic, it was nowhere to be found… they walked back that claim.

Considering Portland’s bike ridership numbers have gone down substantially in recent years, it is surprising to read the opposite is true for active transportation statewide. The Breakfast on Bikes article calls this out, questioning why ODOT would use data from more than 10 years ago to calculate progress on statewide bike goals and saying the dashboard “misuses that data for unwarranted optimistic ends.”

“There are no grounds from this one data point to infer any great progress. And from the Portland bike counts, it looks like there are strong grounds to infer a lack of progress,” the article states. “On the whole the dashboard looks like slick bells and whistles and greenwash rather than substance.”

At the same time as the website lauds statewide active transportation progress, ODOT says at the current rate of investment, it will take over 150 years to close gaps in pedestrian and bike infrastructure. But they go on to say funding for this purpose “has improved in recent years,” referencing the $255 million in federal funding for active and public transportation the Oregon Transportation Commission approved in 2020 as well as the $30 million allocated for biking, walking and rolling projects over the next five years from the Infrastructure Investments and Jobs Act.

To reduce VMT or not to reduce VMT? That is the question…

As mentioned earlier, the dashboard outlines two objectives: to reduce vehicle miles traveled (via things like investing in active transportation) and cleaning up the car transportation that does occur. These are good objectives — but they have to work in tandem. Advocates say ODOT’s actions have indicated they are focusing more on the electrification element than the VMT reduction part, at everyone’s detriment.

The website highlights the fact that progress towards cleaning each vehicle mile is driving ODOT’s progress and there are significant gaps remaining when it comes to reducing VMT.

“This objective has the most opportunities for improvement. Trends suggest that Oregonian’s driving habits won’t change much through 2050 if the state doesn’t make progress here,” the website states.

In a conversation with BikePortland yesterday, Cortright pointed out that the advances in clean transportation aren’t necessarily ODOT’s doing. The Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) is the agency responsible for setting fuel standards and managing large parts of the state’s electric vehicle program (including by administering a ban on purchasing new gas-powered cars by 2035). ODOT has been involved in car electrification efforts, but not all the progress can be directly attributed to their work.

Cortright said although ODOT is acknowledging the state hasn’t made adequate progress on reducing vehicle miles travelled (VMT) overall, their departmental focus on increasing car capacity through projects like the I-5 expansion at the Rose Quarter flies in the face of this stated concern.

“It’s not that we don’t know what it will take to reduce emissions,” Cortright said. “We need to stop expanding highways.”

Underlining Cortright’s message is a recent interaction he had with Oregon Transportation Commissioner Lee Beyer at the March commission meeting. At this meeting, Cortright made the case that ODOT needs to do more to reduce VMT in order to significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Beyer’s response wasn’t encouraging to Cortright and other advocates.

“That’s more of a societal attitude issue rather than something that I think [ODOT] can do directly,” Beyer said. “I think as we move to less environmentally damaging cars, EVs or whatever, that people will continue to drive, because they like the freedom of personal mobility.”

All in all, it’s apparent that ODOT staff and the commissioners overseeing the agency have varied perspectives about how the state is going to reduce its transportation-related emissions. According to Beyer, electrification is the most reasonable step, because it’s too difficult to change people’s behavior. But ODOT knows VMT reduction is a crucial part of the equation.

“Yes, we need to electrify the fleet, but that doesn’t get us there. In terms of vehicle miles traveled reduction. We really need to change the way we provide options for people if we’re going to accomplish that,” Cortright said at the OTC meeting. “And I think people do respond when we provide an environment and choices other than driving.”