It’s been just over two years since we sounded the alarm that a major effort at the Oregon Department of Transportation to better understand the state’s electrification needs was missing a key ingredient: bicycles. Despite skyrocketing sales growth and vast potential to serve the mobility needs of many Oregonians, ODOT’s Transportation Electrification Infrastructure Needs Analysis (TEINA) initiative barely considered e-bikes at all. It gave just passing reference to them as “micromobility” devices and perpetuated the false idea that only cars and trucks can be EVs.

With the release today of the Electric Micromobility in Oregon (EMO) report, ODOT has taken a big step to remedy that oversight. BikePortland was given an early look at the report and we were able to ask one of its authors a few questions about it.

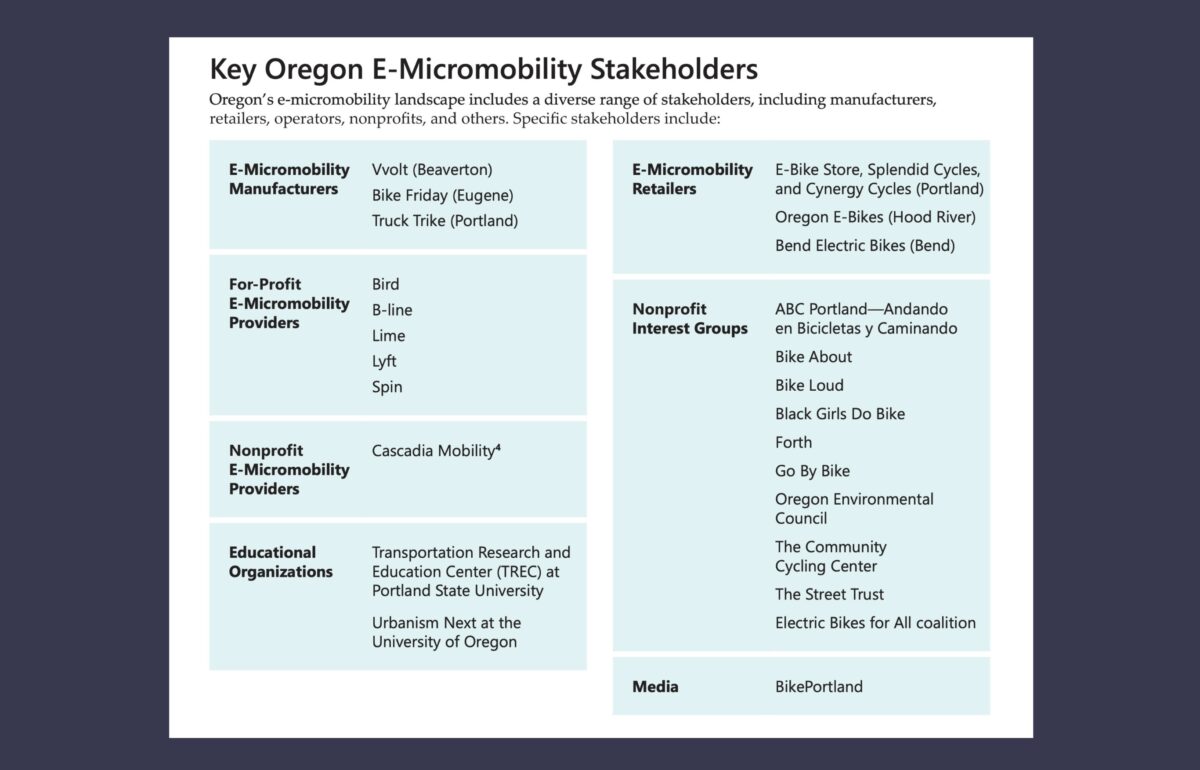

The report comes out of ODOT’s Climate Office. It was co-created for ODOT by Kittelson & Associates and the nonproft electric vehicle group, Forth. John MacArthur, a noted e-bike expert from Portland State University’s Transportation Research and Education Center (TREC) was also on the team that produced the report.

In addition to being the first and most supportive document on e-bikes ever produced by ODOT, the 40-page EMO report gives bike advocates and policymakers a lot to chew on. It considers the use of e-bikes and scooters both by individuals and as part of shared rental programs like Biketown. The report should also put wind in the sail of House Bill 2571, the e-bike rebate bill currently being considered by the Oregon Legislature (the bill’s first public hearing was recently postponed in part to give lawmakers and supporters time to digest this report.)

The report still categorizes bicycle EVs as “micromobility” alongside electric scooters, segways, and other devices. This is unfortunate because no one outside wonky bubbles knows what “micromobility” is, which makes it easy for policymakers to forget about and marginalize. (I prefer to not use that term because I want people to think of bicycles when they think of EVs (since bicycles are technically electric vehicles as per Oregon law), so I’m going to start using “micro-vehicles” and see how that fits. The report also gives a nod to electric freight delivery trikes, which are hardly “micro”. ) With this small framing quibble aside, the reports findings should help further ensconce electric bicycles into Oregon’s transportation policy framework.

In addition to giving elected officials, advocates, and policymakers an excellent overview of the e-bike market and its exciting potential, the report offers a solid list of recommendations and “actionable strategies” that will be necessary to reach it. Just as important as the solutions it outlines is how the report clearly lays out the challenges that face more widespread adoption.

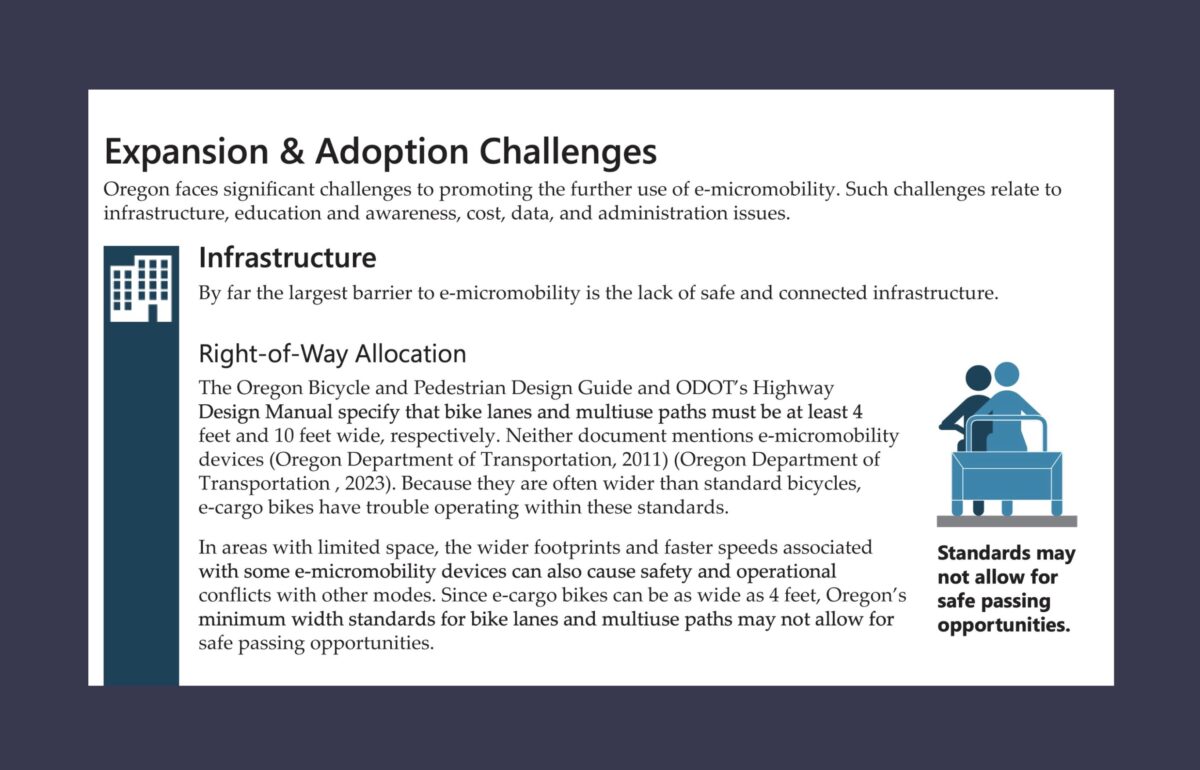

In a finding that will surprise no one who’s been around the bike advocacy space for more than a week or so, the report states that, “By far the largest barrier to e-micromobility is the lack of safe and connected infrastructure.” This is a problem advocates have raised a flag about for many years in calling for wider and more protected lanes for e-bike and scooter use. The report calls out this lack of safe space specifically in a section titled, “Right-of-Way Allocation”:

The Oregon Bicycle and Pedestrian Design Guide and ODOT’s Highway Design Manual specify that bike lanes and multiuse paths must be at least 4 feet and 10 feet wide, respectively. Neither document mentions e-micromobility devices (Oregon Department of Transportation, 2011) (Oregon Department of Transportation , 2023). Because they are often wider than standard bicycles, e-cargo bikes have trouble operating within these standards. In areas with limited space, the wider footprints and faster speeds associated with some e-micromobility devices can also cause safety and operational conflicts with other modes. Since e-cargo bikes can be as wide as 4 feet, Oregon’s minimum width standards for bike lanes and multiuse paths may not allow for safe passing opportunities.

According to the report, lack of space on the road is just one infrastructure problem we need to fix. The others are a lack of secure parking, a lack of integration with public transit (for shared systems), and the lack of charging. This last point is something we’ve harped on for years (only to have many folks tell us it’s not an issue because e-bikers can just charge at home), so it’s nice to see this issue spelled out in the report. “Not everyone can easily charge their device at home,” it reads. “People who make longer trips or use their e-bikes more frequently may also need access to public charging.”

Other major challenges listed in the report include: high purchase costs for micro-vehicles; the need for data from bike and scooter share providers; making sure access to them reaches underserved communities; a confusing regulatory environment; a lack of awareness of micro-vehicles in general, and a lack of funding to operate shared bike and scooter systems (especially for smaller cities)

Beyond the call for more road space for micro-vehicles, the other two major policy recommendations that caught our eyes were strong support for e-bike purchase incentives and a call for Oregon to establish “zero-emission delivery zones” to reduce congestion and emissions.

Jillian DiMedio is a senior transportation electrification analyst at ODOT’s Climate Office and was one of the report’s chief authors. Check out our Q & A with her below:

Why did ODOT commission this report?

In 2021, ODOT published its Transportation Electrification Infrastructure Needs Analysis (TEINA), which identified Oregon’s electric vehicle charging needs over the next 15 years as the state works to meet the zero emission vehicle goals outlined in Senate Bill 1044. While this study included electric micromobility as one of its nine transportation use cases, it became clear early on that this rapidly growing sector has its own unique benefits and barriers that needed to be more closely researched and understood by ODOT. This sentiment was echoed by the micromobility stakeholders that participated in TEINA listening sessions in the Spring of 2020.

In short, ODOT wanted to better understand a rapidly growing sector which will play an important and growing role in serving communities’ transportation needs and in reducing GHG emissions from transportation. The study sought to answer questions about the industry – its history and impact in Oregon, the benefits of and barriers to adoption and best practices and strategies for encouraging widespread use.

Where will this report live, administratively-speaking?

This study is not an official planning document but rather a research paper conducted to enhance understanding of a rapidly growing industry. ODOT’s Climate Office and Public Transportation Division, both of which work on micromobility, are developing an approach to implement the relevant recommendations in the study.

I do also want to note that ODOT just recently hired a new staff member in the Public Transportation Division (PTD) – a Micromobility and First/Last Mile Program Coordinator – that will be dedicated to promoting micromobility in Oregon. This person will develop and implement at statewide strategy for first/last mile connections with a focus on micromobility options, and will certainly be referring to the report’s findings and recommendations as part of this effort. She will also support ODOT’s existing Transportation Options program and the new Innovative Mobility Program, as well as PTD’s broader efforts to build an integrated, statewide public and active transportation network.

What was your goal with this report?

ODOT is committed to reducing emissions from the transportation sector. This means electrifying cars, trucks and buses and using cleaner fuels, and it means reducing the miles driven in Oregon by supporting transportation choices such as transit, biking and walking. The emergence of electric micromobility devices presents a unique opportunity to advance these efforts, as these devices are appealing to a broad range of users and have diverse applications. ODOT recognizes that the increased use of electric micromobility devices like e-bikes and e-scooters is an important tool in the toolkit for reducing the climate impacts of transportation.

With this in mind, the goal of the study was to do a deep dive into the electric micromobility industry – industry trends, the market potential, best practices from around the world in promoting adoption – so that we and other decision makers in Oregon could make educated decisions about how to design policy and programs to support continued rapid adoption.

What do you feel is the number one thing ODOT should prioritize from the report’s recommendations to encourage e-bike and scooter use?

What is clear from the study conclusions is that successfully promoting electric micromobility in Oregon will require a collaborative approach across many jurisdictions and stakeholders. There is a lot ODOT can do to facilitate the growth of this industry alongside our partners. As highlighted in the study, safe and connected infrastructure is a key factor in promoting and supporting the adoption of e-micromobility. ODOT will continue to prioritize the expansion of supportive infrastructure, as demonstrated by ODOT’s growing investments in programs like Great Streets, Safe Routes to School and the Innovative Mobility Program.

The study also highlights the need for a supportive ecosystem, which includes secure parking facilities, public charging, the availability of adaptive devices and equity-centered programs and policies. ODOT can serve as a convener for this supportive ecosystem. And we know that outreach and education are essential to shift the perception of e-bikes from one where they are used primarily as recreational devices to one where they are considered viable modes of transportation, for all sorts of activities. Lending libraries and shared micromobility programs can help shift the perception and ODOT will continue to promote these as well.

You can learn more by reading the full report or check out the executive summary if you are pressed for time.