In response to climate and transportation activists who are wary of expanding I-5, both Interstate Bridge Replacement Program (IBRP) leadership and politicians who voted ‘aye’ on the project have gestured to a consolation prize. IBRP planners – correctly – point out that the current bridge is unfriendly to people using active transportation, given the small path dedicated to biking and walking with dangerous gaps and little protection against the three lanes of car traffic in either direction. They say the vehicle lane expansion is just part of the project, and that it will also include improved facilities for people to walk, bike and roll between Portland and Vancouver.

But what good is nice infrastructure if it’s too steep to easily use?

Just before Portland-area government agencies were set to vote on the IBRP’s Locally Preferred Alternative, the U.S. Coast Guard wrote a letter to project staff saying the replacement bridge design will need to provide at least 178 feet of vertical space so large ships can pass underneath. Transportation advocates already bristled at the idea of asking bicyclists to climb 116 feet as called for in the LPA design. An additional 50+ feet of height makes the situation even more dire.

The Problem With a Tall Bridge

Engineers have two options to ensure bridges have manageable grades: go low or go long. Biking across the existing I-5 bridge is far from ideal, but because it has a lift span to accommodate shipping vessels, at least it’s not very high off the ground (about 72-feet high). Getting from the ground to the bridge doesn’t require a significant climb, and the bridge doesn’t extend too far past the river.

With a fixed height of 178 feet, however, a bridge would have to be very long – about two miles – in order to meet the grade requirement of 4%. This would have an especially profound impact on downtown Vancouver, which is located just on the other side of the bridge. Even a 116-foot-tall bridge will require completely new infrastructure. And a 4% climb over two miles is nothing to scoff at in itself.

As a comparison, Portland’s Tilikum Crossing has an average incline of just under 5% for about a third of a mile, and this can feel difficult to traverse on tired legs. But the Tilikum Crossing, devoid of car traffic, makes up for the climb. I can’t imagine pedaling across a freeway bridge for two miles with the roar of traffic in your ear could provide that same balance.

To transportation and climate activists, this is just another example of the IBRP hastily pushing forward with a freeway expansion with not enough attention paid to the needs of people who aren’t in cars.

The Skeptics

Ahead of the City of Portland vote to support the bridge, members of the Portland bicycle and pedestrian advisory committees wrote a joint letter (PDF) to city leadership to hold off on supporting the project until they can make sure the height will “accommodate the 8-80 year old cyclist and allow for wheelchair users to access the bridge without significant effort.” The letter says mockups of the project area “gloss over the impact of height,” which makes it difficult to fully evaluate the sufficiency of walking, biking and rolling facilities.

When Just Crossing Alliance issued an action alert asking Metro at Portland City Council to force the IBRP to include more bridge design options in the LPA, the first point on their list was that it have, “gentler grades for freight and people walking, rolling and biking.”

IBR program leaders maintain the bridge will be manageable for people walking, biking and rolling – and also say they’ll be able to negotiate with the Coast Guard to keep it at 116 feet. But economist and IBR data watchdog Joe Cortright thinks they’re downplaying the seriousness of the Coast Guard’s requirement.

“The Coast Guard’s conclusion makes it clear that it is strongly committed to maintaining the existing river clearance, that it won’t approve a 116 foot bridge, and that the economic effects of this would be unacceptable,” Cortright wrote in City Observatory earlier this month. “Still, the [Oregon and Washington State Departments of Transportation] are equivocating, implying that the Coast Guard decision has no weight…and implying that the Departments of Transportation and not the Coast Guard are the ones who determine the minimum navigation clearance.”

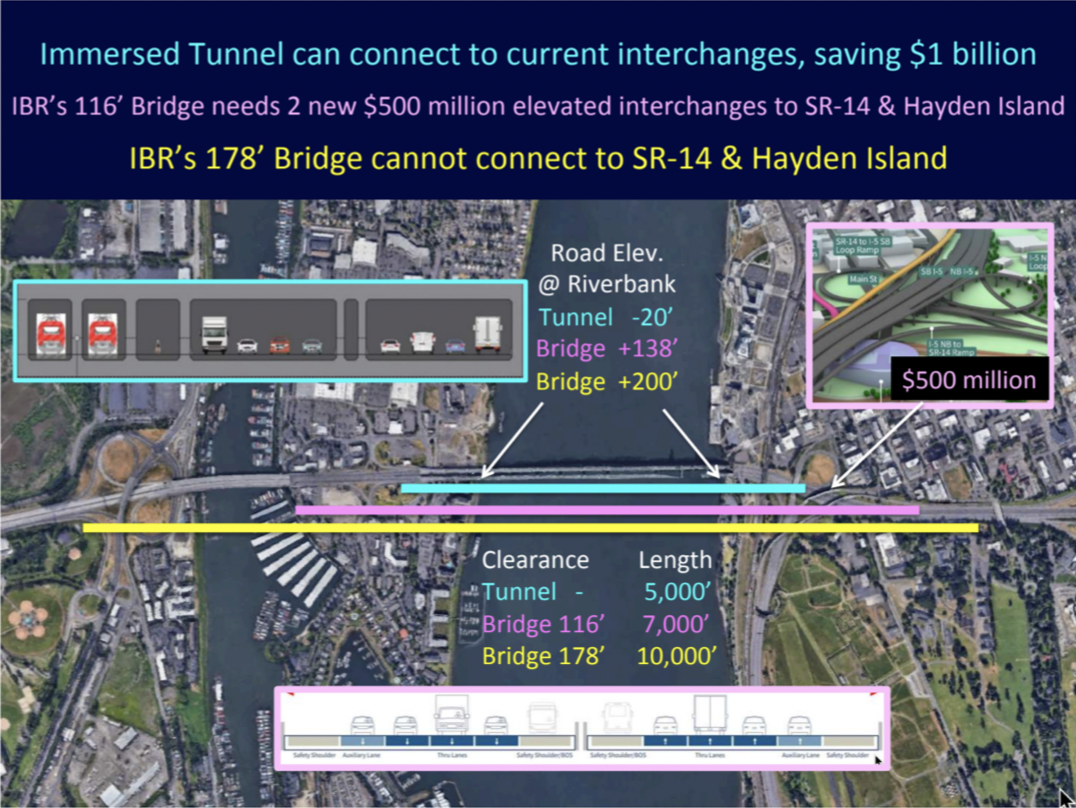

IBR administrator Greg Johnson says they can’t use a different design like a tunnel or lift feature – both of which the Coast Guard suggests as feasible alternatives – citing logistical problems that critics dispute.

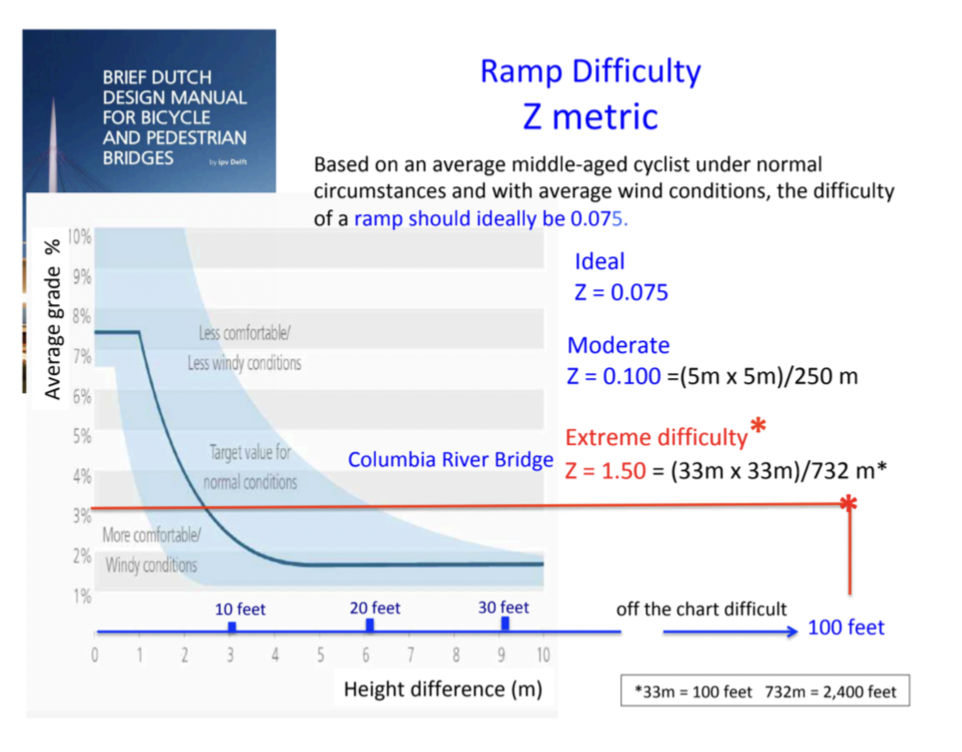

Retired engineer Bob Ortblad, one of the IBRP’s most outspoken critics, has been strongly advocating for an immersed tube tunnel concept in part because he says it solves the incline problem. Ortblad has investigated Dutch design manuals for best practices in designing bridges suited to bicyclists, and he found that considering the height and length of the IBRP, they would deem the strenuousness of this bridge unfathomable. According to the Dutch, an average grade of 4% is only acceptable if the bridge is 10 feet off the ground. Anything taller than that should max out at under 2%.

Any improved active transportation facilities will gather dust if the bridge is too high. A would-be Vancouver to Portland bike commuter may peer up at a path 178 feet in the air and decide it’d just be easier to drive a car.