This is the story of the little ADA ramp that could.

For 14 months now, I’ve watched a new ramp in the Portland Heights neighborhood (south of Goose Hollow) get built, fail inspection, be torn down, get rebuilt, fail inspection, be torn down, get rebuilt again . . . you get it. Apparently the third build still needs some adjustment to the adjacent sidewalk.

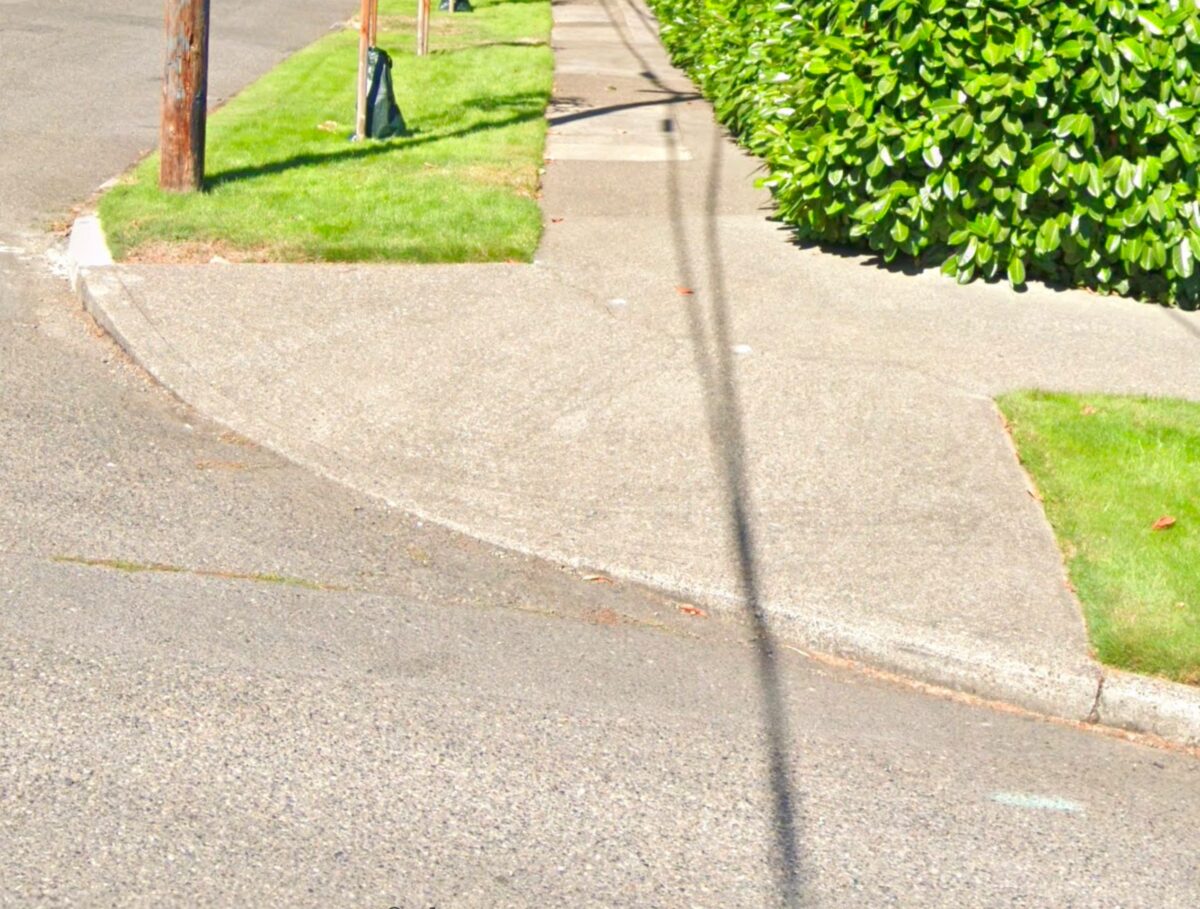

Here’s a photo diary of the recent attempts to build the new ramp at SW Spring and 16th streets:

If this were the story of just one hapless corner I probably wouldn’t be posting about it. But there are two nearby locations with new ramps which have also had to be rebuilt.

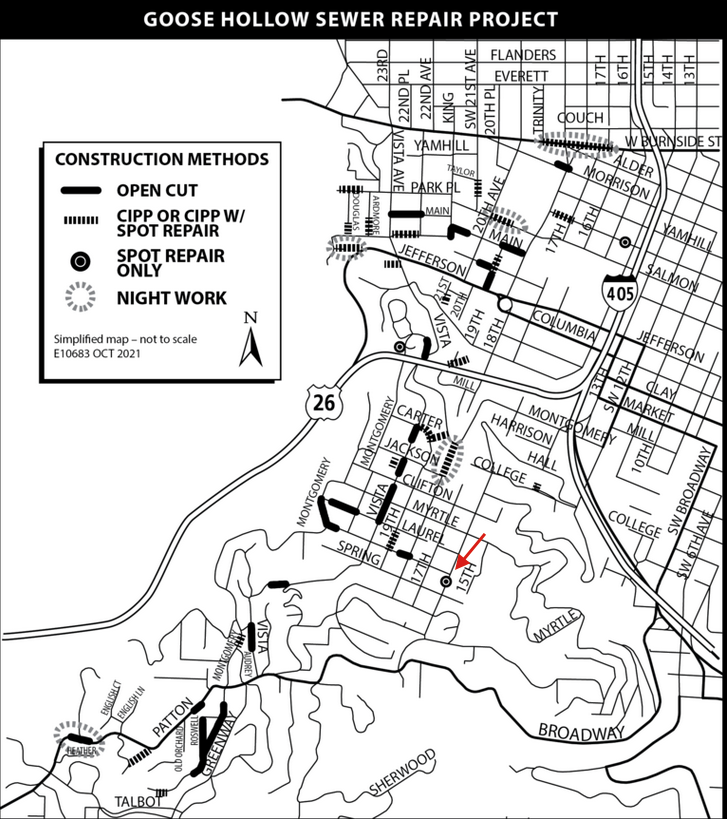

The ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act) work has been triggered by the Goose Hollow Sewer Repair Project, a Bureau of Environmental Services project to upgrade aging and deteriorating sewer pipes in Goose Hollow and Portland Heights. These old pipes have been around between 80 and 100 years, as have some of the sidewalks.

The primary work of the project, replacing sewer pipes, has gone well. The crews work their tails off, they have been friendly, accommodating, communicative, and aside from all the dust, a pleasure to be around. They have replaced two and a half miles of public sewers.

If this were the story of just one hapless corner I probably wouldn’t be posting about it. But there are two nearby locations with new ramps which have also had to be rebuilt. So far that totals seven pours for three ramps. I’m not trying to find the weak link(s) in a work-flow that involves many subcontractors. However, at some point(s) the city has to have touched the process (at least through inspections) before the concrete pours.

This week, it looks like the strategy with the third rebuild is to call the ramp good, and instead to adjust the slope of the adjacent sidewalk. Hopefully, the job can be finished with this new approach. It’s a tough corner, the high point of both a north-south and a east-west slope. And the specifications for contemporary ADA ramps don’t easily sit on legacy sidewalks.

I don’t know who eats the cost of these rebuilds in the short-term — the contractor or the city — but in the end, the taxpayer gets the bill.