“The question is do we want to increase capacity, and I say no.”

— Jo Ann Hardesty, Portland city commissioner

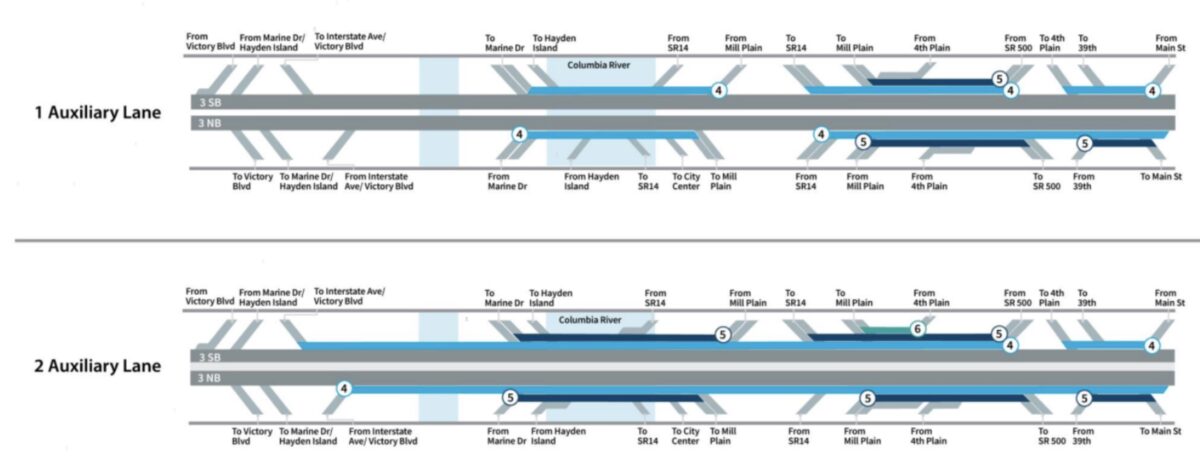

After months of analyzing options for what a remade I-5 could look like between Washington and Oregon, the Interstate Bridge Replacement Program today put two options on the table: a highway expansion with the same footprint as the 2013 proposal for the Columbia River Crossing, or a second option, which shaves off 16 feet and includes one fewer “auxiliary” lane in each direction.

Focusing heavily on the short distances between the seven interchanges included in the project (below), the project team Thursday touted reduction in crashes that could come from adding additional auxiliary lanes, an argument familiar to anyone following our coverage of the I-5 Rose Quarter project. But future auto travel times were front-and-center, using a model out to 2045 that includes the Rose Quarter project as a done deal.

“Auxiliary lanes…are not through lanes and not the same as adding an additional lane,” the voiceover stated on a video shown to the IBR’s executive committee promoting the benefits of “ramp-to-ramp connections”. But Washington DOT Secretary Roger Millar wasn’t convinced that they had enough information to make a full assessment of the safety benefits that could come with one or two more lanes. “I need to see safety data, because that’s what we were selling aux lanes on before. That will be more important to me than saving two minutes 25 years from now,” he said.

The travel time forecasts are all over the place, with a trip from I-205 in Vancouver to I-5’s connection with I-405 in Portland during traditional morning commute hours still expected to increase from 29 minutes to 57 minutes with the addition of two auxiliary lanes compared to 63 minutes with no project at all. But the projected decrease in travel time heading the other direction, from 38 minutes in 2019 to 15 minutes with two auxiliary lanes, is clearly central to the entire project. Millar, calling those travel times a “bright shiny option”, suggested they were a fantasy and that the road capacity would be filled by induced demand, though he didn’t use that term himself.

Advertisement

A two-auxiliary lane option could mean a 12-lane I-5 through Vancouver, which will already be significantly impacted by elevating I-5 through downtown, as renderings released earlier this month show. The diagrams also suggest that only adding 1 auxiliary lane would have less of an impact on Hayden Island.

It’s clear elected leaders still have a lot of questions about this project but the momentum to get everyone to sign off on a Locally Preferred Alternative by the start of summer is intense and would take a lot of effort to slow down.

Portland Commissioner Jo Ann Hardesty did not express any confidence in the traffic models being presented during her questions to project staff but was instead pushing the highway project to expand its definition of equity, which the presentation framed as increasing modal options and vehicle travel times for everyone. “Equity is more than increasing modal options,” she said. “Equity is also about ensuring that we’re not exacerbating costs for low income community members. Your equity definition should be expanded.”

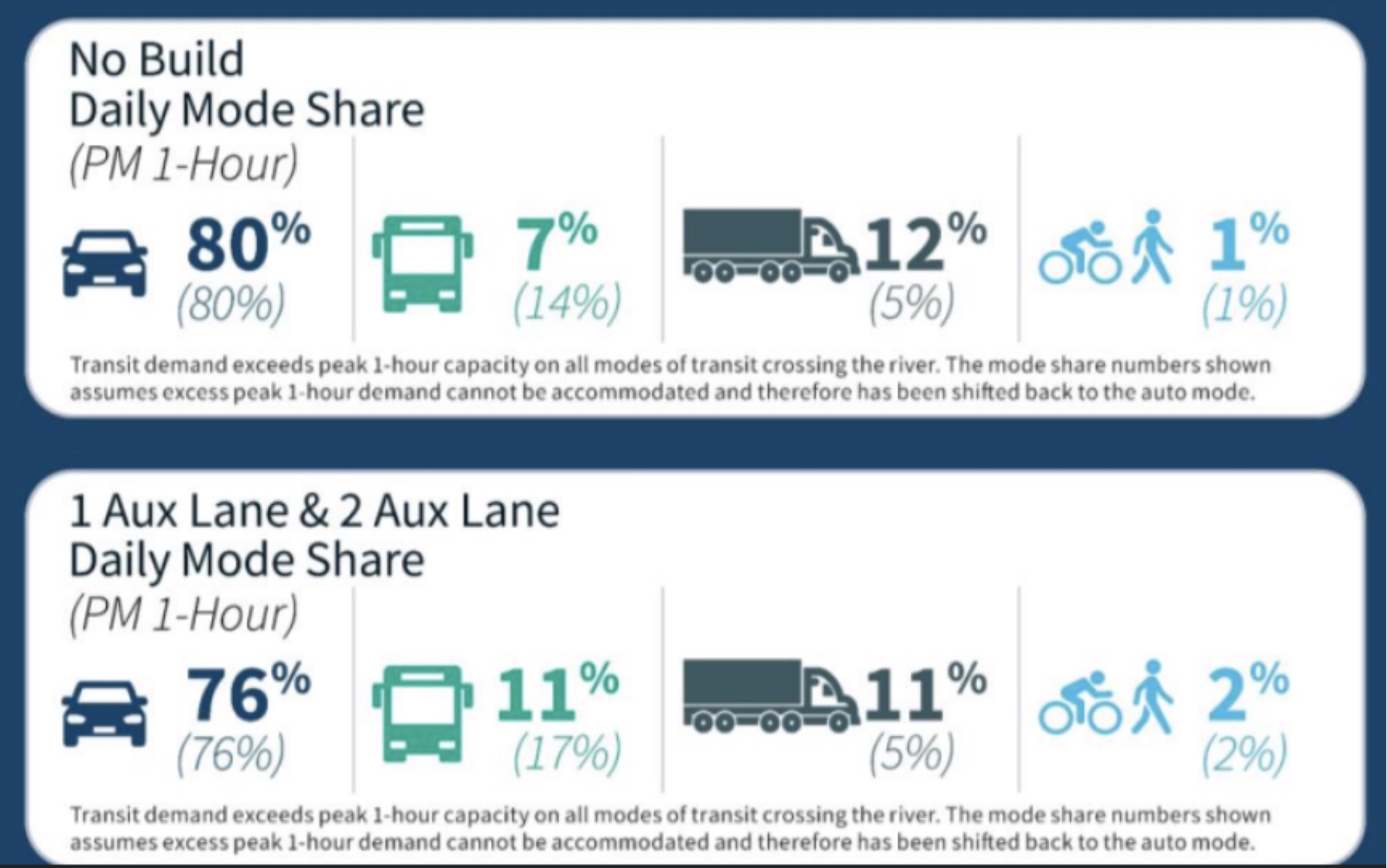

With a wider I-5 with either one or two auxiliary lanes, the project is only projecting the percentage of people crossing the bridge by walking or biking to increase from 1% to 2% in the next two decades, with the share of people crossing via transit increasing from 7% to 11%. (We’ll have a separate full post on the transit options up soon.)

“In your modeling, are you assuming that human behavior will change at any point between now and 2045?”, Hardesty asked in a primarily rhetorical question to project staff, expressing a desire to see the region move toward not oriented toward getting around via car in the next two decades. “I don’t know how we can model for 2045 without taking into account climate, and BIPOC communities and how they’re going to be impacted by this,” she said. “The question is do we want to increase capacity, and I say no.”

Metro President Lynn Peterson, on the other hand, signaled that she thought the one auxiliary lane option was closest to what the Metro Council, which includes some of the project’s most skeptical voices, has been advocating for. Shaving one auxiliary lane off the project could save $75-$100 million dollars out of what could be a $4.8 billion project. In two weeks, we’ll learn whether the full blown Columbia River Crossing option has been the one picked to move forward, or its slightly slimmed down version.

It’s clear elected leaders still have a lot of questions about this project but the momentum to get everyone to sign off on a Locally Preferred Alternative by the start of summer is intense and would take a lot of effort to slow down.