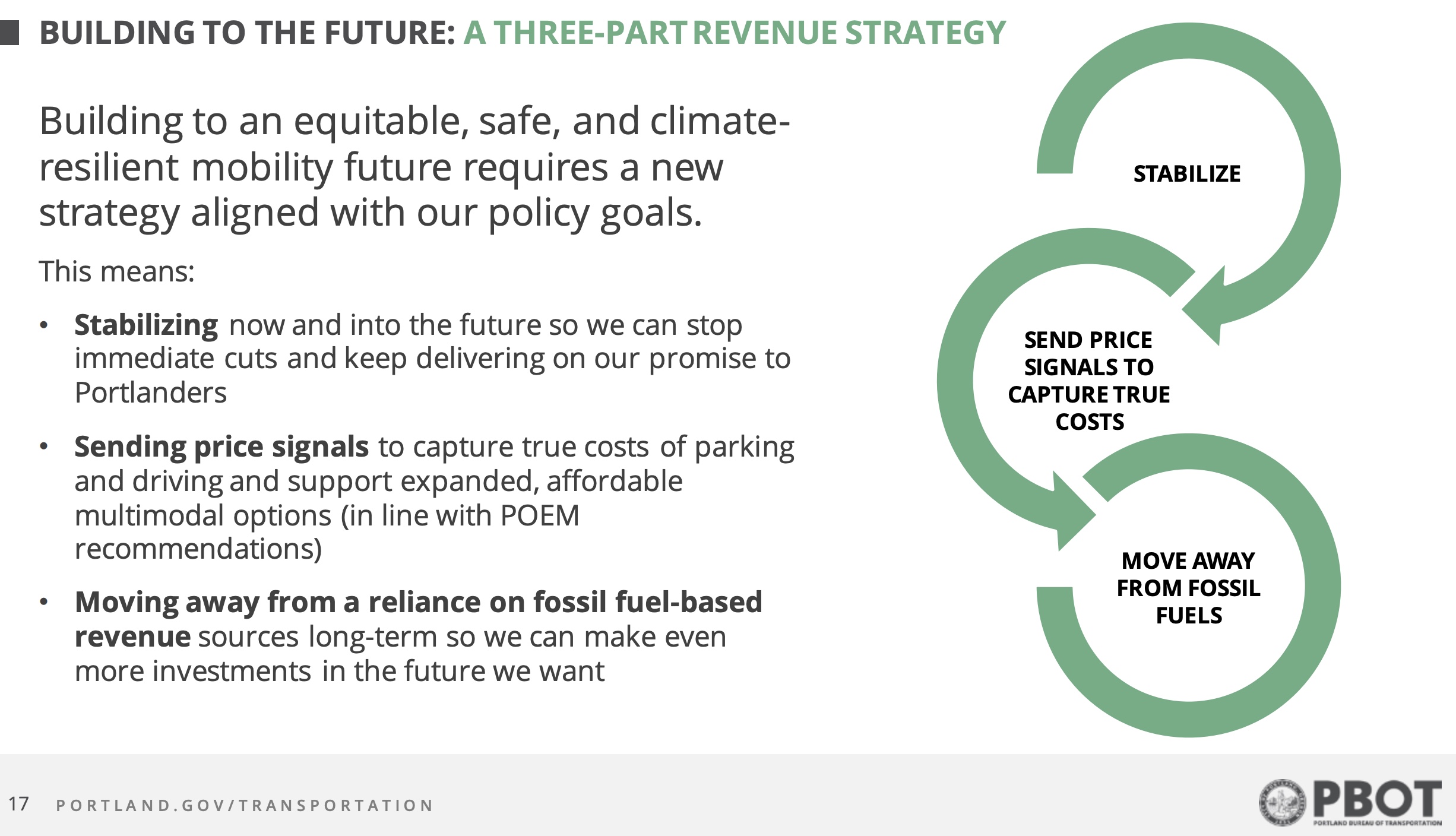

Can the Portland Bureau of Transportation manage its budget deficit while also working to shift the city’s transportation system away from reliance on fossil fuels? With its new revenue strategy, that’s exactly what it’s aiming to do.

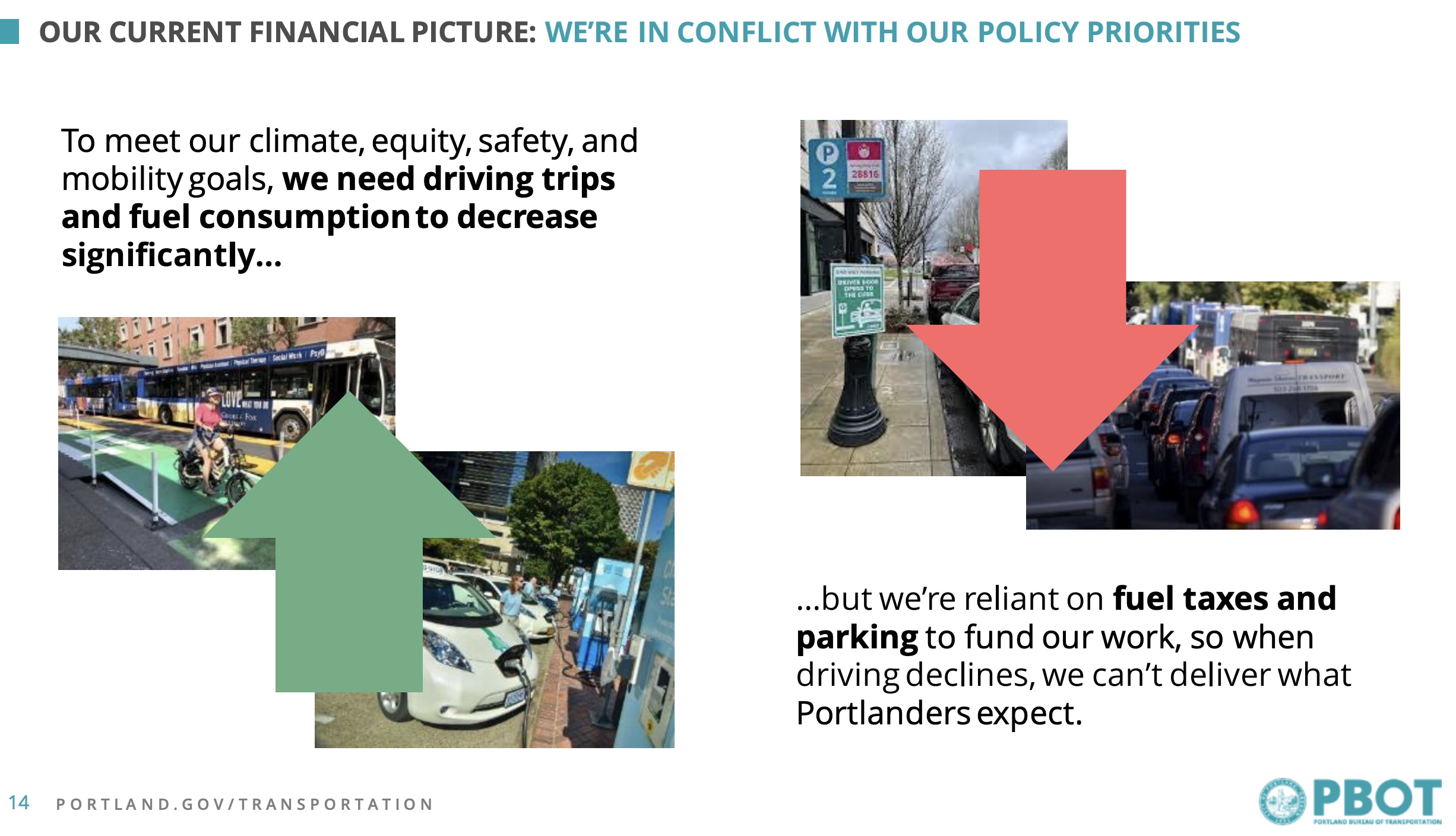

As we’ve explored in the past, PBOT’s reliance on parking fees for revenue has been financially and environmentally destructive. It has created a catch-22: If PBOT wants to reduce Portlanders’ vehicle miles traveled (VMT) and curb carbon emissions, they’ll need to fund programs and projects that encourage options to driving cars and trucks. But in order to pay for them, they need parking revenue.

“This is an unsustainable situation,” said Portland Commissioner Jo Ann Hardesty, who heads PBOT, at the February 23 City Council meeting where she and her colleagues voted to pass a new revenue strategy to address it.

The near-term solution, according to PBOT, is its “Bridge to the Future” proposal. Here are the core policy measures, followed by key slides from their council presentation:

A parking “Climate and Equitable Mobility” transaction fee of $0.20 added to metered parking transactions starting this summer to “send price signal to drivers about the costs of driving and support investments in transportation affordability and access.” Staggered parking permit increases beginning this year to achieve cost recovery. Performance-based parking and inflationary rate increases starting in 2023, which will bring base meter rates up $0.40 per hour to adjust for inflation, and adjust rates in the future to account for demand and inflation.

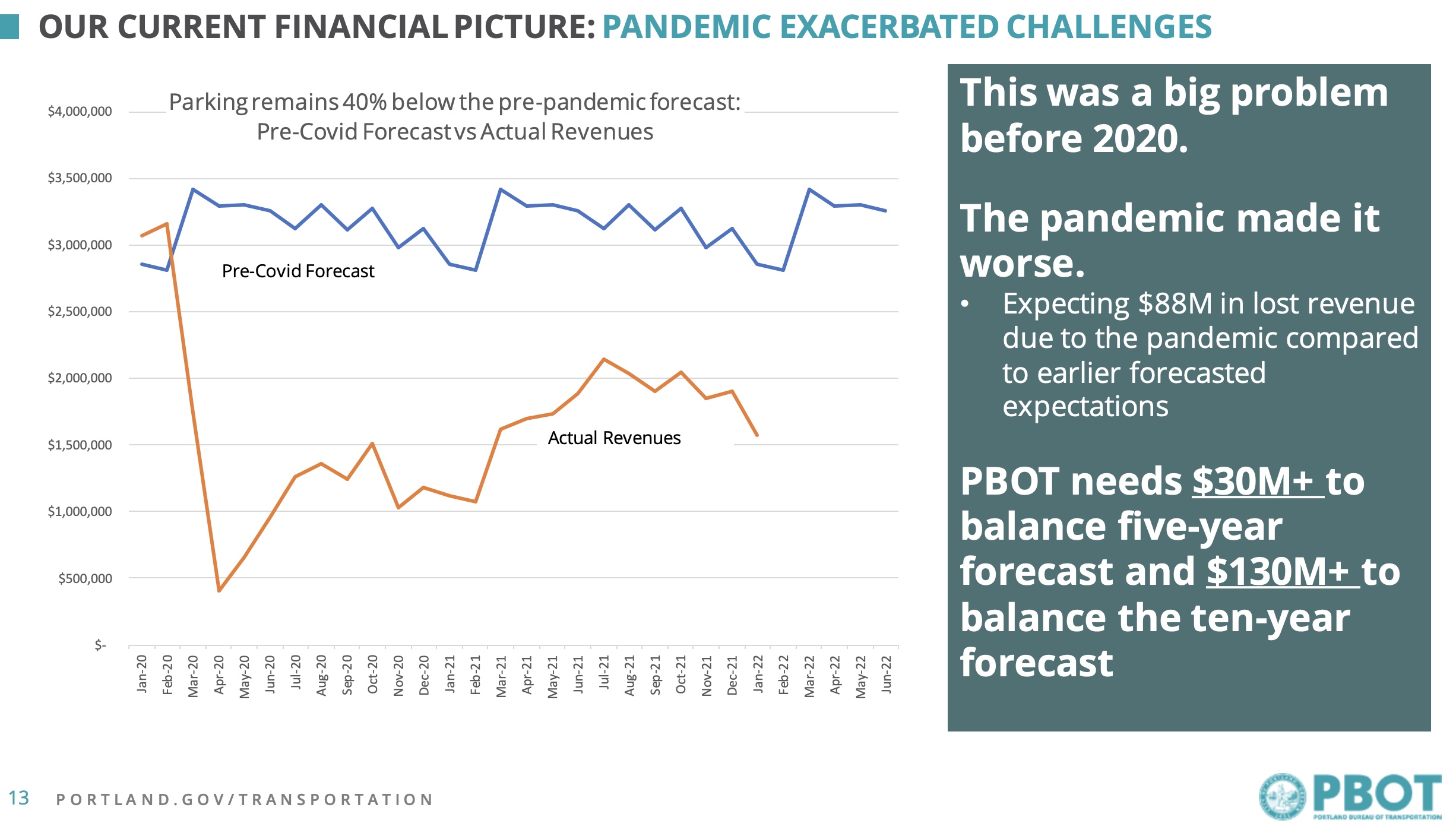

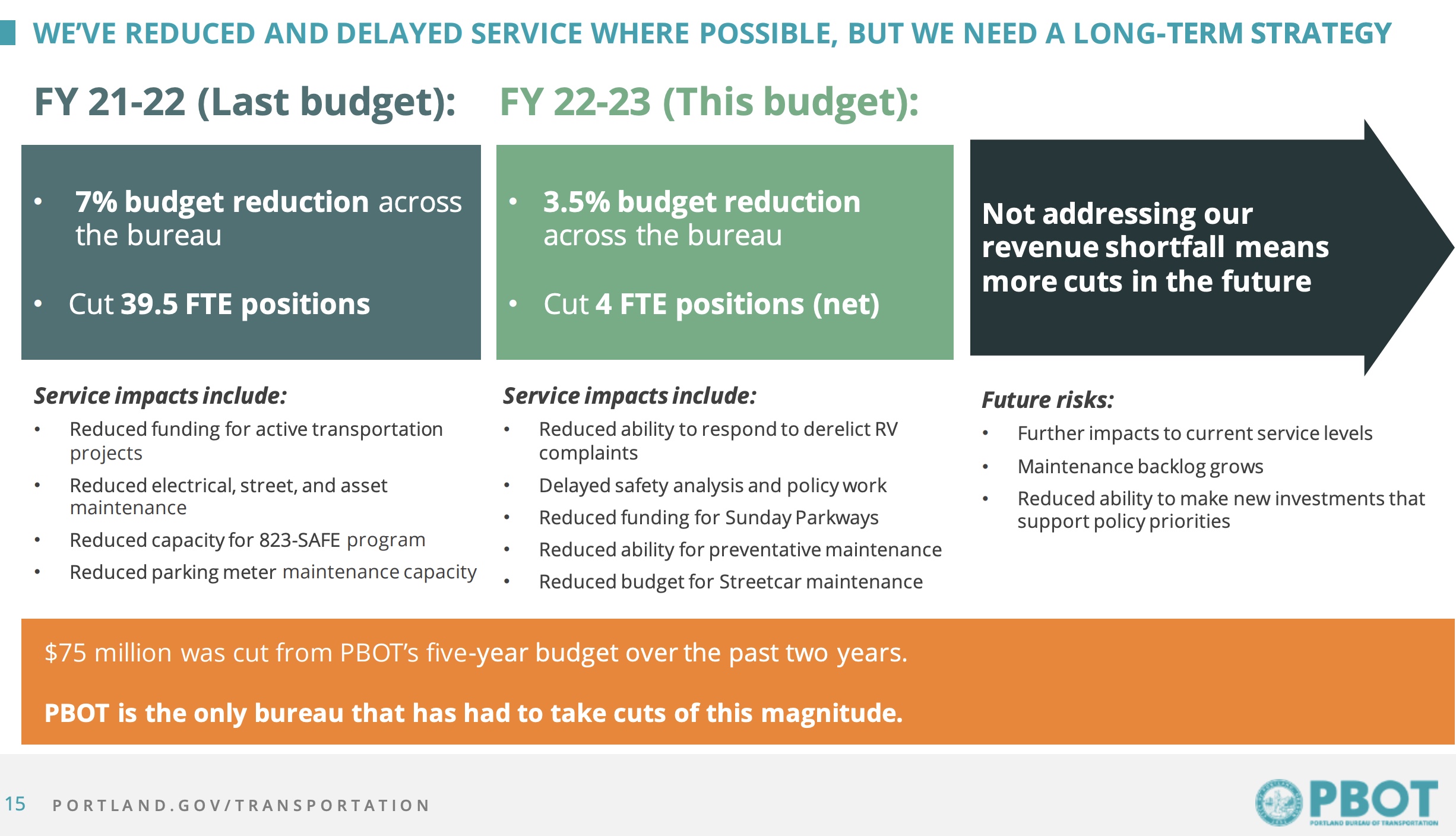

Parking revenue currently accounts for 35% of PBOT’s annual discretionary revenue and rates have not been increased since 2016. And unlike the Water or Environmental Services bureaus, PBOT does not increase meter rates with inflation. The agency had cut their budget to the bone even before Covid ravaged it with an estimated $88 million in lost revenue.

The Budget Office estimates the new on-street parking fee will generate about $2 million per year and it will go directly toward programs that encourage people to walk, bike and take transit (like PBOT’s Transportation Wallet program). The rate increases that will start in 2023 are expected to generate $24 million in gross revenues.

Advertisement

But there’s a bigger picture to see here beyond new revenue. As urban transportation reformers will tell you, parking has long been subsidized in order to hide some of the external costs of driving a single-occupancy vehicle. With this parking fee, PBOT wants to capture those externalized costs and explicitly remind drivers about them.

A Portland Mercury article from last week summed up the approach and asked Tony Jordan from Parking Reform Network what he thinks about it:

For people whose primary form of transportation is driving, these fee hikes may seem sudden and pricey. For parking reform advocates, the price increases are a baby step in the right direction.

Tony Jordan, director of the Parking Reform Network, sees parking pricing as a key tool to combat car dependency. To Jordan, an adequate parking price is one that equalizes supply and demand. Ideally, according to Jordan, there should always be one parking spot available on a block or a given parking area. That way, there is always a spot available for the driver who needs it, but not so many spots open that the wide availability encourages people to drive because it’s so easy to find parking in the area.

In populous shopping areas like NW 23rd Avenue, achieving that equilibrium might mean $3, $4, or $5 per hour—whatever it takes to leave space available for people who have to park in the area while encouraging others who have the option to walk, bike, or ride public transit to do so. According to Jordan, if parking spots were priced at their market-rate value, it would illuminate the true cost of driving and foster a larger shift towards public transportation, triggering greater investments in public transportation due to the increased demand.

“We use market pricing for a lot of things,” Jordan said. “It’s weird that parking is where people draw the line.”

After these near-term programs are implemented and PBOT achieves some budget stability, it will start looking to mid-to-longer term plans for being able to stay on its feet without the help of parking fees. This may include things like property or payroll taxes going to transportation projects instead of revenue coming solely from transportation or right-of-way use fees.

It’s amazing PBOT was able to get a parking rate increase through council without attracting opposition, especially amid record high gas prices. If it’s to have the desired impact, and continue to avoid controversy, we’ll have to make sure alternatives to driving are as competitive as possible.