(Photo: Jonathan Maus/BikePortland)

“[The project] needs to demonstrate how it won’t contribute to elevated rates of asthma and hospitalization for Black and brown Portlander…”

— Jo Ann Hardesty, Portland city commissioner and Executive Steering Group member

After months of discussion about process and “vision and values”, the project team behind the second attempt to expand I-5 between Washington and Oregon finally presented a set of design options for the five mile highway project to elected leaders from around the region last week.

These were described by project administrator Greg Johnson as the “universe” of options that fit the purpose and need of the project, unchanged since the failed Columbia River Crossing project was given Federal approval in 2011. After all of the signs in the past year have been pointing toward just a recycled version of the CRC, it will surprise few readers here to learn that there are now just three options for the highway itself left in the “universe”, and they all have ten traffic lanes.

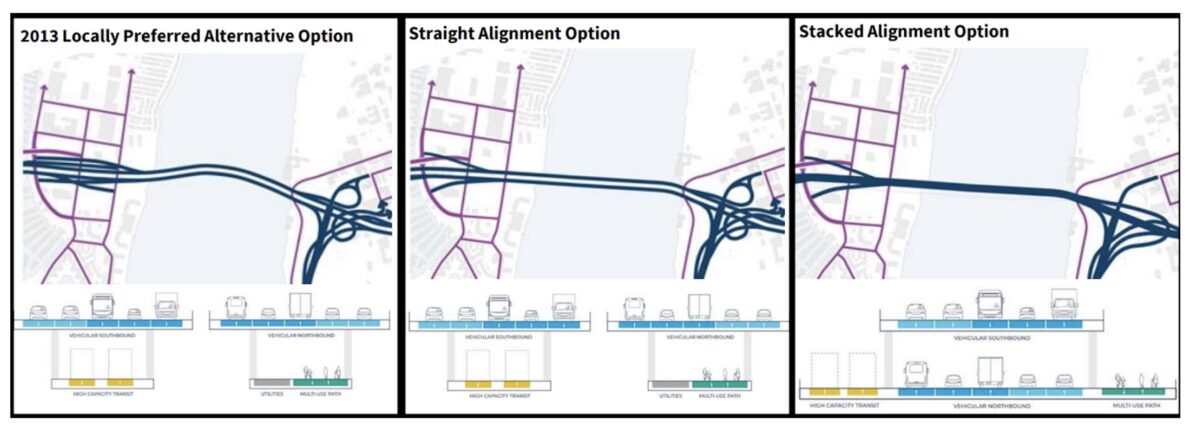

Two of the designs are identical in cross-section: the selected design from the CRC, with two bridges carrying five lanes each with space for transit on the lower level of one and a multi-use path on the lower level of the other. Another tweaked design straightens out the alignment, which would be “less complex” to construct, per project documents. And a third option stacks five highway lanes on top of the other five, with transit on one side and the multi-use path on the other. This design would “minimiz[e] impacts to the natural environment and surrounding areas”, according to the memo on the proposed designs.

Advertisement

Of course, the number of lanes shown is one thing. Project specs that leave room for additional lanes down the road are another, as City Observatory has repeatedly shown with both the Columbia River Crossing and ODOT’s related project in the Rose Quarter.

Ten options for public transit across the river were also outlined but given essentially zero scrutiny among the leaders. Those options include three Bus Rapid Transit (BRT), four light rail (LRT) options, and a bus on the shoulder of I-5. All those transit options as well as the multi-use path are being treated as the extent of the climate considerations between the highway design options. No matter the design of the highway, space for transit, walking, and rolling will “create appealing and effective transit and active transportation opportunities” leading to decreases in emissions, per project documents.

Advertisement

It’s not at all surprising that the narrow set of outcomes proposed now are nearly identical to what was developed ten years ago, given the fact that adding a climate lens directly to the project’s purpose and need, or using a broader definition of equity when it comes to project outcomes was discarded to keep the project on an accelerated timeline. The question is what happens next.

“What would it look like if there was a more robust transit, a more robust congestion pricing program, what does that do to demand?”

— Lynn Peterson, Metro president and Executive Steering Group member

During the meeting, there was some pushback on what the project team brought forward. Commissioner Jo Ann Hardesty, as she has at past Executive Steering Group meetings, signaled that what was being presented fell short, but not in a way that suggested that the very fast timeline to get the project designed should in any way be hindered. “My concern is that the design options for the bridge alignment and interchanges have been developed in a way that suggests that we already know what the solution is.” she told the group after signing off on the list of project outcomes that includes faster travel times on I-5.

Commissioner Hardesty was clearly not comfortable saying that the three options for the proposed highway were the entire “universe”. “[The final design] needs to demonstrate how it won’t contribute to more 124 degree days like we experienced just this last summer in the Lents neighborhood in Portland. It needs to demonstrate how it won’t contribute to elevated rates of asthma and hospitalization for Black and brown Portlanders, which normally are the recipients of the negative outcomes of freeway activity,” she told the group. “Are we really moving the project forward in a way where we can be confident that, in the design options we will explore, that we are addressing these very core issues?”

Metro President Lynn Peterson was the other voice in the room pushing back, explicitly asking for an additional highway design option to act as a “bookend”. She suggested that option should look at “what would it look like if there was a more robust transit, a more robust congestion pricing program, what does that do to demand, so that we can actually see how that works and what elements are playing with what?” Peterson said the assumptions on how pricing may impact demand for the highway seem “too muted” at this point. But Peterson referred to this as an “outer limit” design, suggesting that it would primarily be useful to the group as a comparison to the other proposed designs.

Peterson is having to navigate the fact that she’ll have to sell any outcome of consensus at the Executive committee back to the full Metro Council, which includes members who are skeptical of where the project is headed. (We’ll have more coverage on that side of the project soon.)

Last week’s meeting was also a test of the degree to which the community groups that the project team has created, the Community Advisory Group and the Equity Advisory Group, will be truly listened to in the process. Lynn Valenter, a co-chair of the Community Advisory Group, abstained from giving a yes or a no on the proposed design “universe” because the CAG or the EAG hadn’t even had the material presented to them yet. Those groups are a big part of the strategy in avoiding the outcome of ten years ago, but will their input meaningfully change the outcome?

This week, we’ll learn what Oregon and Washington legislators think about the “universe” of options as the project steams toward a final “IBR solution” by the end of March. By the end of the year, it will be pretty clear if this project will meaningfully change to reflect the reality of those 124 degree days that Commission Hardesty brought up, or if we’re still trapped in the CRC reality.

— Ryan Packer, @typewriteralley, ryan@theurbanist.org

— Get our headlines delivered to your inbox.

— Support this independent community media outlet with a one-time contribution or monthly subscription.