Story by Peter Welte

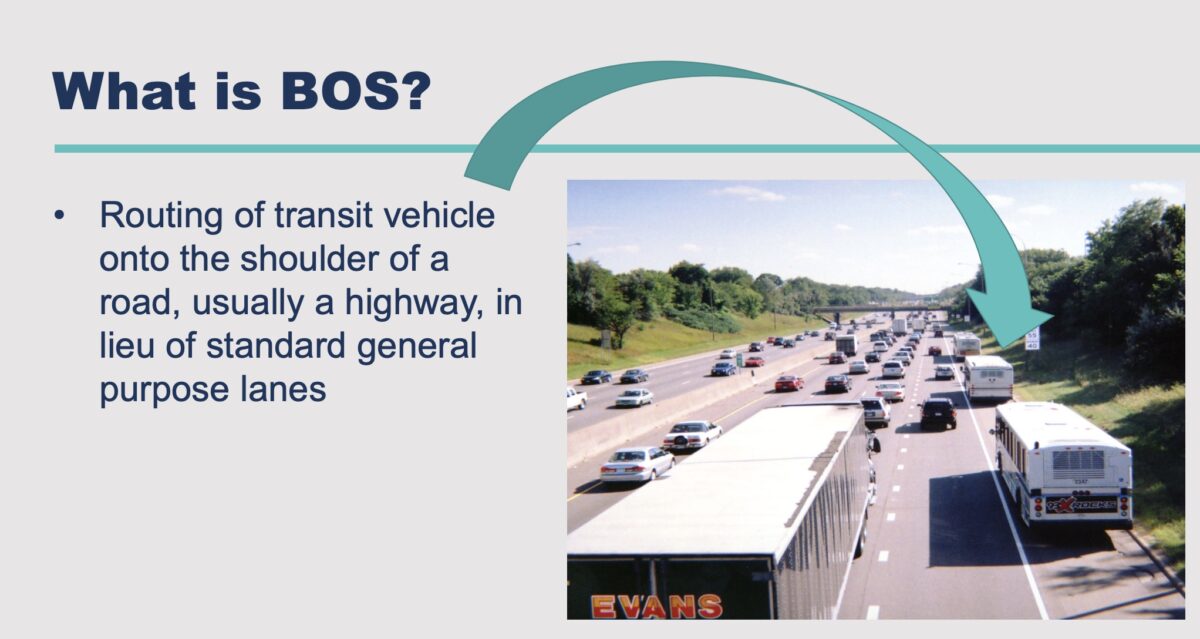

After two years of planning, Wilsonville’s South Metro Area Regional Transit (SMART) agency is finally ready to turn on their blinkers and drive their buses onto the shoulder. On Tuesday, SMART is hosting a kick-off celebration for the launch of their bus on shoulder (BOS) pilot project with the Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT).

Starting in November, SMART will be pulling buses on their 2X line off to the side of ODOT’s I-5 freeway when traffic slows — in order to zoom past backed-up traffic along freshly repaved 12-foot wide shoulders.

ODOT deserves credit for thinking outside the lanes and doing something the former highway department has rarely (if ever?) done: help mass transit move faster than single occupancy vehicles. However, whether you bike, walk or bus, there are a few details in the margins which may be worth a closer look.

What’s in it for SMART?

Despite setting a goal for itself of having 92% of trips be “on time”, SMART’s 2X line was “on time” or early only about 74% of the time in October. ODOT believes this project will help give transit users a more reliable commute, and SMART anticipates an improvement in “on-time performance” from 74% to a range of 85%-90%. When the general traffic lanes drop below 35 mph, SMART’s buses will be allowed to take the shoulder and go up to 35 mph.

Improving reliability and demonstrating better “on time performance” could be one way SMART can stand out should it choose to apply for the kind of competitive federal funding that could help the agency buy more and bigger buses to meet demand (induced, hopefully, by SMART service improvements like this).

The more congested the freeway, the better it is to be riding the bus. According to A Guide for Implementing Bus On Shoulder (BOS) Systems (PDF). “Even a very short segment of BOS shoulder in a 5-mph traffic segment can yield substantial travel time savings,” that guide says. “For example, a quarter-mile segment with 5-mph speeds could save buses more than 2 minutes of running time.” And riders actually over-estimate how much time they save: “Passengers tend to perceive travel time benefits at two to three times the actual savings. Since perception directly influences mode choice decisions, even small savings can be important.”

So, more traffic should mean more riders, and skipping traffic means better “on time performance” which could mean more ability to grow operations (or at least scale back up; COVID cut the average weekday passenger trips in half for the 2X line).

What’s in it for transit riders?

Starting in November, SMART’s 2X line will have three solid selling points: Faster commutes, more predictable travel times, and on-board Wi-Fi. Plus, if all goes well, additional transit demand could lead to more buses, more often, as well as (possibly) additional routes.

What’s in it for people walking or biking?

Let’s get the obvious out of the way: If you walk or bike to the bus and there’s heavy traffic, you’ll have a few less minutes for doom-scrolling via the free Wi-Fi while the bus zips past traffic.

Despite myriad benefits, ODOT’s freeway shoulder bus operation will be no panacea. Driving buses down I-5’s shoulder could present unpredictable hazards such as debris, disabled vehicles, people biking or walking (remember: this is allowed on Oregon freeways in most places, including where ODOT’s pilot project is). We asked ODOT if they added additional lighting, as the “bus on shoulder” guide suggests for this context. They didn’t.

Also on the safety note, keep in mind that bus drivers won’t use the shoulder when visibility is poor, the bus will never be operated at more than 35 mph in the shoulder, and it can only go 15 mph faster than traffic. Hence, BOS is not exactly BRT (bus rapid transit) or anything close: if traffic is completely stopped, the bus speed is capped at 15 mph.

BikePortland reached out to public transit planning and policy consultant Jarrett Walker to ask: Could this be a first baby step toward BRT?

He wasn’t too optimistic:

“The premise of BOS is ‘Given that we’ve built this freeway as it is, and don’t have a bus lane, can we get some use out of the shoulder to get buses past traffic?’ It’s a kludge. It’s not BRT for all the reasons you can imagine. Shoulders are also for disabled vehicles and in some cases for bikes. Merges at every interchange are tricky, because motorists don’t expect a vehicle to be running along the shoulder. All those uses introduce a lot of uncertainty into the bus operations. But is it better than nothing? Sometimes, especially in the short term, and transit agencies often take what they can get.”

Authorized Use Only

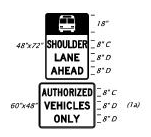

ODOT provided BikePortland an image of the shoulder signage, however no one we spoke with – other than ODOT – thought the signage chosen (“Authorized Vehicles Only”) clearly communicates that the shoulder is still a designated space where people on bikes are expected and allowed.

Scott Kocher, a Portland-based safe transportation advocate and lawyer, was surprised when he saw it. “I’d want to see more signage alerting authorized drivers that there are pedestrians and bikes on the freeway shoulder.”

When asked to clarify, an ODOT spokesperson commented via email: “The authorized and priority uses of shoulders are: emergencies (and emergency vehicles), law enforcement vehicles, disabled vehicles, maintenance vehicles, bicycles and pedestrians. Transit must yield to all these priority uses.”

The signs (which are consistent with the standards outlined in the Manual of Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD) are used to inform motorists of the authorized use per state law. However, “bus on shoulder” operations are far from universal (only about a dozen states have implemented it), and the MUTCD does not appear to provide specific advice for appropriate signage. The sign ODOT selected is documented in the 2009 (most current) edition seems to speak more to “official” vehicles than the everyday Jane or Joe on a bike may think they are.

We looked around the country to see if there’s some established best practice. We hoped to find something in NACTO or MUTCD or AASHTO or one of the other TTWFOMLAs (“transport things with five-or-more letter acronyms”) but no luck. The state that pioneered “bus on shoulder” in 1991, and has around 300 miles of it, is Minnesota, and even their signage is confusing.

Google did turn up a sign that seems to be least confusing, below. (Minnesota road. Credit: Google Maps)

Still, ODOT insists it is clear, and safe: “… the operational requirement for buses to use this space is to yield to all other legal uses of shoulder. SMART’s bus operator training includes this topic.”

Share the Road

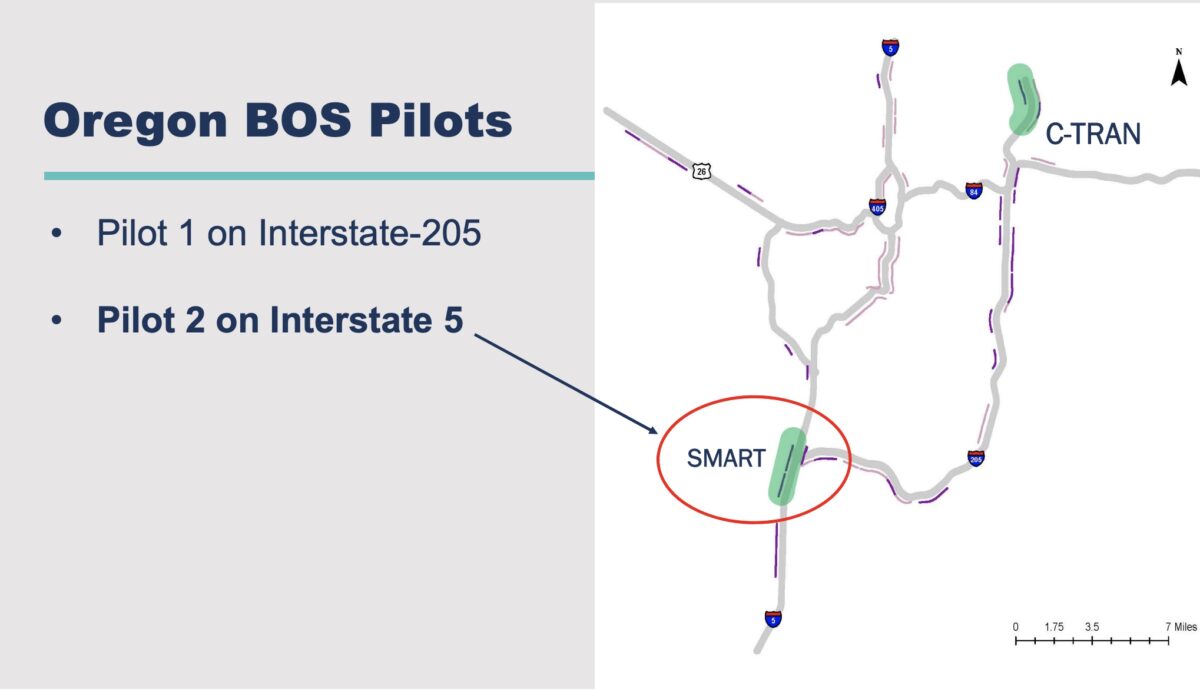

ODOT has been eying the shoulder for some time. Although SMART’s pilot is the first of its kind for an Oregon agency, C-TRAN was petitioning ODOT for access to the shoulders of Glenn Jackson (the bridge, not the man) years ago. Not long after that, in February 2019, TriMet applied for a $150,000 grant to study an express bus network which would “draw on ODOT’s existing analysis of the feasibility of Bus on Shoulder service”. Ultimately, TriMet’s report would find that a hypothetical evening-peak 12 mile trip from the I-205/I-5 interchange to Clackamas TC could save at most 3.5 minutes by using the shoulders. However, it also found that because people spend so much time waiting for buses or stopped at all the many stops they’re not disembarking at, simply adding frequent buses that stop less often would save a great deal of time too (e.g. 14 minutes on on Line 6, MLK Jr. Blvd).

Thus, those broad shoulders may look great to transit operators, but they aren’t the only way to get a better ride.

At the same time, sharing that space effectively preempts any chance of creating separated infrastructure for human powered transport. All the while technically complying with Oregon’s “Bike Bill”, which requires “accommodation” for people biking on any reconstructed facility; that’s exactly what ODOT has achieved by authorizing (through administrative rules) people to walk or bike on the shoulder.

Hau Hagedorn, chair of ODOT Oregon Bicycle and Pedestrian Advisory Committee (OBPAC), has spent much time thinking about how and when ODOT does or does not improve conditions for people biking on the freeway.

She’s concerned with projects like this or a shoulder expansion happening on I-205, ODOT is actually making conditions less safe for people cycling — and instead of acting in the spirit of the Bike Bill to properly accommodate people on bikes, ODOT could simply change their own rules to un-authorize people biking if conditions worsen. “People who bike and walk are allowed to do so on freeway shoulders unless ODOT prohibits it per the OAR. … The OAR allows ODOT to say that these sections are way too dangerous for people biking and walking.”

Get On The Bus

ODOT and SMART will host their pilot project kickoff event at Wilsonville Transit Center (9699 SW Barber St.) on Tuesday, Oct 26, from 12:00 to 1:00 pm. Speakers include ODOT Director Kris Strickler, Wilsonville Mayor Julie Fitzgerald, Tualatin Mayor Frank Bubenik and others.

The pilot project will run for one year, and just like on their C-TRAN I-205 pilot, ODOT is collecting a variety of quantitative and qualitative data related to safety, general operations, impacts to infrastructure, and transit performance. SMART, for their part, has trained their drivers in the classroom, and on the road, and says they put safety as their primary concern.

If all goes well, perhaps both SMART and ODOT will realize the full potential that’s possible when massive-occupancy public vehicles are allowed to properly compete with single-occupancy private vehicles. If so, perhaps they’ll see the merit in converting one of the slow lanes to a true bus rapid transit lane.

But if not, there’s always the trusty bike or e-bike, which can usually do more than 15 mph when traffic is at a standstill.

— Peter Welte

— Get our headlines delivered to your inbox.

— Support this independent community media outlet with a one-time contribution or monthly subscription.