Oregon is facing urgent environmental problems which are attracting the national media. Last month, The Atlantic published a gripping piece about the heroic response of Molalla residents in fighting the converging Beachie Creek and Riverside fires last fall. This week, The New Yorker ran an article on our “heat dome” event earlier this summer.

This looming climate catastrophe is the difficult backdrop against which Portland Bureau of Transportation (PBOT) project managers present their plans. Last week, the Portland Bicycle Advisory Committee (BAC) meeting heard an update on PBOT’s Streets 2035 plan from project manager Matt Berkow.

As we’ve reported, the purpose of Streets 2035 is to deliver a framework for resolving competing demands on rights-of-way, with the end goal of identifying

a right-of-way allocation framework that moves streets forward to achieve citywide objectives, minimizes the need for an exception process, and helps bureau staff achieve a predictable and transparent process for themselves and external stakeholders.

Streets 2035 is currently in its middle phase, cross-bureau technical conversations seeking to identify “opportunities for flexibility,” and hopes to finish up in 2022. Berkow has a tough job ahead of him. Engineers rely on tables and standards which are often used to justify a “no” rather than to create a path to “yes.”

Advertisement

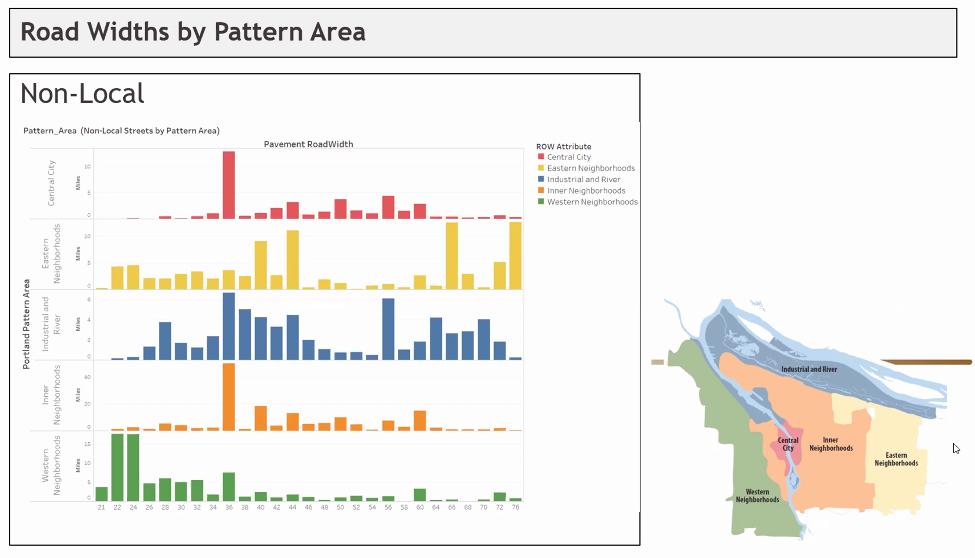

One of Berkow’s most informative slides was “Road Widths by Pattern Area” (below) which clearly shows that East Portland has the lion’s share of our city’s 76 foot wide roadways.

But BAC member (and The Street Trust executive director) Sarah Iannarone was not an easy sell. She brought up tree canopy, communication between bureaus, and amenities across wide spaces and ended by exclaiming, “Where is the innovation coming from?” Indeed, East Portland’s wide streets and lack of tree canopy are deadly problems which urgently require solutions.

Maybe Iannarone brought up innovation because she had heard the same lecture at PSU’s Transportation Research and Education Center (TREC) that I had listened to a couple of weeks earlier. Urban Planner Adam Millard-Ball gave a talk titled “Turning Streets Into Housing.” Although Millard-Ball’s talk focused on housing prices and residential streets, it is not much of a stretch to apply his arguments to mixed used and commercial areas, and to substitute housing for parklets, tree-filled promenades and taco-trucks.

In the spirit of innovation, let’s look at some of his ideas.

Millard-Ball is hot off an article titled The Width and Value of Residential Streets published in the Journal of the American Planning Association. The article is an economic analysis of the value of streets and their opportunity cost which, he argues, informs the question of how wide a street should be. He calculates the combined value of the residential streets in 20 US counties as nearly $1 trillion. And he makes the case that this wasted value ends up constraining housing supply and inflating the price of housing, especially in already expensive coastal areas.

In what reads almost like a response to Streets 2035, he writes:

The planning and design discourse, however, has largely focused on how to divide up a given quantity of land between competing uses; that is, how to allocate a fixed street right-of-way. Less attention, either normatively or empirically, has been paid to how much urban land is or should be devoted to streets. The tradeoff between land for streets and land for other urban uses—parks, housing, commerce, public facilities, and so on—is implicit or ignored altogether.

His TREC talk was simpler than the paper, and more provocative. Using a 60-foot wide suburban street in San Jose as an example, Millard-Ball calculates that the ROW in front of each house is worth almost $250,000. He makes a strong argument that a residential street doesn’t need to be more than 16 ft wide, and suggests reclaiming much of the ROW for additional, front-yard Accessory Dwelling Units. (below)

This might seem outrageous at first, and I found myself wondering how it would go over at a Portland neighborhood association meeting, but some cities are already part way there. The New York Times ran an excellent story last week about the Clairemont neighborhood in San Diego which is experiencing an ADU boom. The San Diego real estate market is terribly expensive, leaving many people who grew up in San Diego unable to buy a house as adults. The Clairemont Mesa area was developed as modest, middle-class subdivisions in the 1950s. It also happens to be centrally located. The article described the competition between residents building backyard ADUs and adding 2nd floors intended for their parents and adult children, and developers looking for a piece of that ADU action, for a profit. It sounded frenzied, and you could imagine some people snapping up any ROW real estate in front of their house they could.

The New Yorker article, titled “Under the Dome” by James Ross Gardner, featured PSU professor Vivek Shandas, who studies urban heat islands. When the heat dome hit, Shandas grabbed an infrared heat camera and a temperature sensor and drove to Lents where he measured an ambient temperature of 124 degrees. His camera registered the surface of the asphalt at 180 degrees. He then drove to the forested Willamette Heights neighborhood in NW Portland, where the temperature was 99 degrees, 25 degrees less.

96 people in Oregon died in the heat wave. Lack of tree canopy and an abundance of asphalt kills. Maybe we can get rid of some of that East Portland asphalt and plant trees.

Innovation and big-thinking are crucial. So is the meat and potatoes of effective local government. It is important that Streets 2035 succeeds. We need all the bureaus, and the groups within bureaus, to be working together toward the big goals of our city.

— Lisa Caballero, lisacaballero853@gmail.com

— Get our headlines delivered to your inbox.

— Support this independent community media outlet with a one-time contribution or monthly subscription.