(Photo: Jonathan Maus/BikePortland)

“Now that the SW Corridor is not funded by the bond measure, are we just going to wait for it to be safe for kids to cross Barbur?”

— Eric Wilhelm, neighborhood transportation activist

For the past several years, much-needed changes to Southwest Barbur Boulevard have been linked to building the Southwest Corridor light rail line. When voters rejected Metro’s transportation funding measure in November, they also voted down financing for that project. TriMet now says the SW Corridor “is on hold.” Even if funding for the SW Corridor project happens as part of an infrastructure package under the Biden administration, it would take years to build.

So the question remains: How much longer will people who walk and roll on Barbur Boulevard have to wait for safety updates that have been badly needed for decades?

This article reviews Barbur’s safety problems with a focus on key intersections and projects in the southern half of the corridor from SW Bertha to Capitol Hwy. A second article will look at the corridor’s northern half.

Advertisement

Background

In 2013, as the Oregon Department of Transportation faced significant pressure to put Barbur on a road diet, BikePortland reported on the tension between advocates pushing for short-term changes while planners and bureaucrats wanted to wait for the longer-term light rail gravy train. “The SW Corridor plan is a visioning process that isn’t expected to result in concrete projects for 10-20 years (if ever),” we wrote. In that same article, veteran Southwest Portland advocate Keith Liden shared that because of its moderate grade and direct route, Barbur, “has enormous potential to be a primary bicycle route between downtown and southwest Portland.”

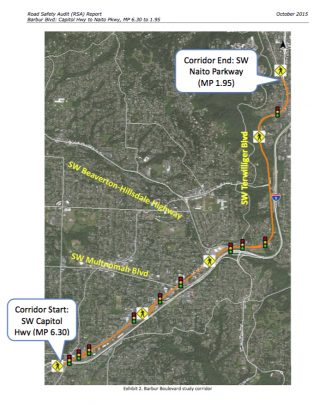

Barbur is one of Portland’s “orphan” highways under the ownership and jurisdiction of ODOT. In 2015, after much community pressure, and with political leadership from then state Rep. Ann Lininger, ODOT solicited an independent Road Safety Audit (RSA), which studied the 4.5 mile Barbur corridor from Naito Parkway to its intersection with SW Capitol Highway. The RSA noted that four other comprehensive studies had been completed in the five years previous to it, including Portland’s 2013 Barbur Concept Plan (2013), the PBOT Barbur High Crash Corridor Safety Plan (2012) ODOT’s Barbur/OR-99W Corridor Safety and Access to Transit project, and Metro’s Southwest Corridor Plan. Some recommendations from these plans have been implemented, including ADA ramps, a few pedestrian medians, improved bike facilities, and reconfigured crosswalks — but the need for larger capital investments remains.

Advertisement

30th Avenue and “The Diagonal”

If this intersection looks familiar it’s because a man in a wheelchair was struck and killed here last month while rolling in the crosswalk.

I spent a bit of time on the corner of Barbur and 30th poking the crosswalk button, but I couldn’t bring myself to actually cross the street, 110 ft without a median felt too exposed to me.

Between the Fred Meyer at Bertha Blvd and the “Crossings” intersection at I-5 and Capitol Hwy, Barbur cuts diagonally through the area’s incomplete grid at a 40-degree angle. This diagonal creates a two-mile long series of irregular intersections, with the north-south streets intersecting Barbur at an acute angle, the east-west streets intersecting at an obtuse angle, and a couple streets making a jog to meet Barbur just right. Although each of these intersections is unsafe in its own way, the intersection with 30th Avenue will serve as a good example of problems common to all of them.

Any skewed street creates a crosswalk which is longer than the width of the street it crosses because the walk lies on the hypotenuse, rather than along the right angle, of a triangle. At 30th Ave., Barbur is about 80 ft wide, but its crosswalk is approximately 110 ft long—the street angle adds about 30 ft to the crosswalk length. In addition to the hazard of a long crosswalk, the turn angles exacerbate sloppy driving habits. Notice that the car turning left onto eastbound Barbur (in graphic above) is about to cut through the left turn lane. Similarly, a car turning right onto north 30th tends to make an early slice through the bike lane.

Advertisement

Good traffic control can improve safety at irregular intersections and the 2011 Barbur High Crash Corridor Safety Plan recommended that pedestrian countdown signal heads be installed at all Barbur signals. However, not only does the 30th Ave signal lack the recommended countdown, but the timing of the pedestrian crossing light surprised me. The crosswalk user gets 30 seconds total to cross Barbur: the “walk” signal lasts about four seconds, followed by a flashing red hand for about 24 seconds, and finally the flashing red turns to solid red for two seconds before Barbur cars get their green light. Nearly half a minute of a flashing “don’t walk” signal strikes me as inviting poor decisions. If the recommended countdown signal head had been in place at 30th Avenue, it might have prevented Clayton Chamberlin’s death.

“I really almost never venture to the 30th and Barbur intersection, this is a very dangerous intersection and I am not at all surprised that many accidents occur there.”

— Katherine Christiansen, Southwest Neighborhoods coalition

I spent a bit of time on the corner of Barbur and 30th poking the crosswalk button, but I couldn’t bring myself to actually cross the street, 110 ft without a median felt too exposed to me. It turns out I’m not alone. Katherine Christiansen, the chair of the Transportation Committee for the Southwest Neighborhoods coalition (SWNI), told me that she also avoids the intersection, “I really almost never venture to the 30th and Barbur intersection, this is a very dangerous intersection and I am not at all surprised that many accidents occur there.” She continued, “I see lots of pedestrians crossing Barbur to get to the bus stop just on the east side, it’s a popular stop and there are many public transportation users in the apartments nearby.” Katherine and I can choose not to cross the street, but it’s a choice some nearby residents don’t have.

A final hazard along the whole diagonal, one which is particularly bad near the intersection with 30th, is the density of driveways which punctuate the streetscape. 30th has over three times as many driveway related crashes as other locations, but the problem is bad all the way from 30th to the Crossings.

The Southwest Corridor Light Rail design would have cleaned up many of these problems and brought consistency to this disordered street segment. The plan was to purchase abutting private property and widen the Barbur cross section to include the train and platform in the middle, while maintaining two travel lanes as well as bike lanes, sidewalks and tree medians in each direction. At 30th, the width of the road, train and platform would have been about 100 ft.

But as southwest bike advocate Eric Wilhelm noted to me recently, “The SW Corridor at $300 million a mile makes the $20-plus million a mile Capitol Hwy project looks like quite a deal.”

The Barbur Crossroads Safety Project a.k.a. “The Jughandle”

The Oregon Department of Transportation is planning one large project on Barbur, the $3 million Barbur Crossroads Safety Project, at the intersection of Barbur, Capitol Hwy and I-5. They plan to begin construction this year. The project would include “many safety elements including a new sidewalk, ADA ramps, pedestrian countdown signals, new illumination, new bicycle markings.”

At its heart, the project is a re-routing of northbound Capitol Highway drivers into a “jughandle” configuration for entry onto the southbound I-5 on-ramp. The jughandle would encircle one of the area’s most popular businesses, Barbur World Foods.

The re-routing is controversial. Many neighbors and transportation advocates prefer a protected left-turn lane and signal on the bridge, which would involve taking a northbound traffic lane. ODOT studied and rejected the protected left-turn option because, “the traffic analysis for this scenario showed a substantial increase in congestion on streets surrounding this intersection.”

Funding for the project comes from the All Road Transportation Safety program. ODOT notes there have been at least 161 crashes in the intersection since 2008 (all the three fatalities that occurred on Barbur in 2020 happened at other intersections).

Eric Wilhelm pointed out that the ODOT’s unwillingness to implement a lane diet will soon leave this segment as, “one of the last few blocks without a decent bikeway between PCC/Lake Oswego and Multnomah Village.”

According to PBOT, Portland had 17 deaths to people walking in 2020. Three of them, or one out of every 5.6, occurred on Barbur Blvd. With no train coming down the tracks any time soon, we must keep a focus on the need for safety updates on Barbur Blvd.

— Lisa Caballero, lisacaballero853@gmail.com

— Get our headlines delivered to your inbox.

— Support this independent community media outlet with a one-time contribution or monthly subscription.