The five-year progress report for the Portland Bicycle Plan for 2030 is five years overdue. That seems like a fitting allegory for the general lack of urgency and institutional respect for cycling in Portland city government right now.

At last night’s meeting of the PBOT Bicycle Advisory Committee, city bicycle coordinator Roger Geller unveiled a draft of that five-year status update. The report details steady progress, but it also reveals our incremental steps forward aren’t nearly enough to reach our goals.

“It’s extremely discouraging to see this lack of progress over a decade,” BAC member Catie Gould said during a discussion that followed Geller’s presentation. “This report should be an alarm bell. We’re never going to hit our goals at the rate we’re going.”

“This report should be an alarm bell. We’re never going to hit our goals at the rate we’re going.”

— Catie Gould, Portland Bicycle Advisory Committee member

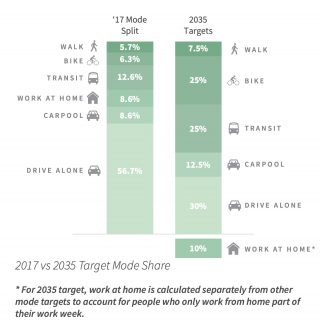

The plan’s top line goal is to have 25% of all trips made by bicycle by 2030 and it included 223 action items to get us there. The report says PBOT has completed just 59 action items (26%) and is currently working on 88 (39%) of them.

When it comes to progress toward our bicycle use goal, the results half-way toward 2030 do not look good.

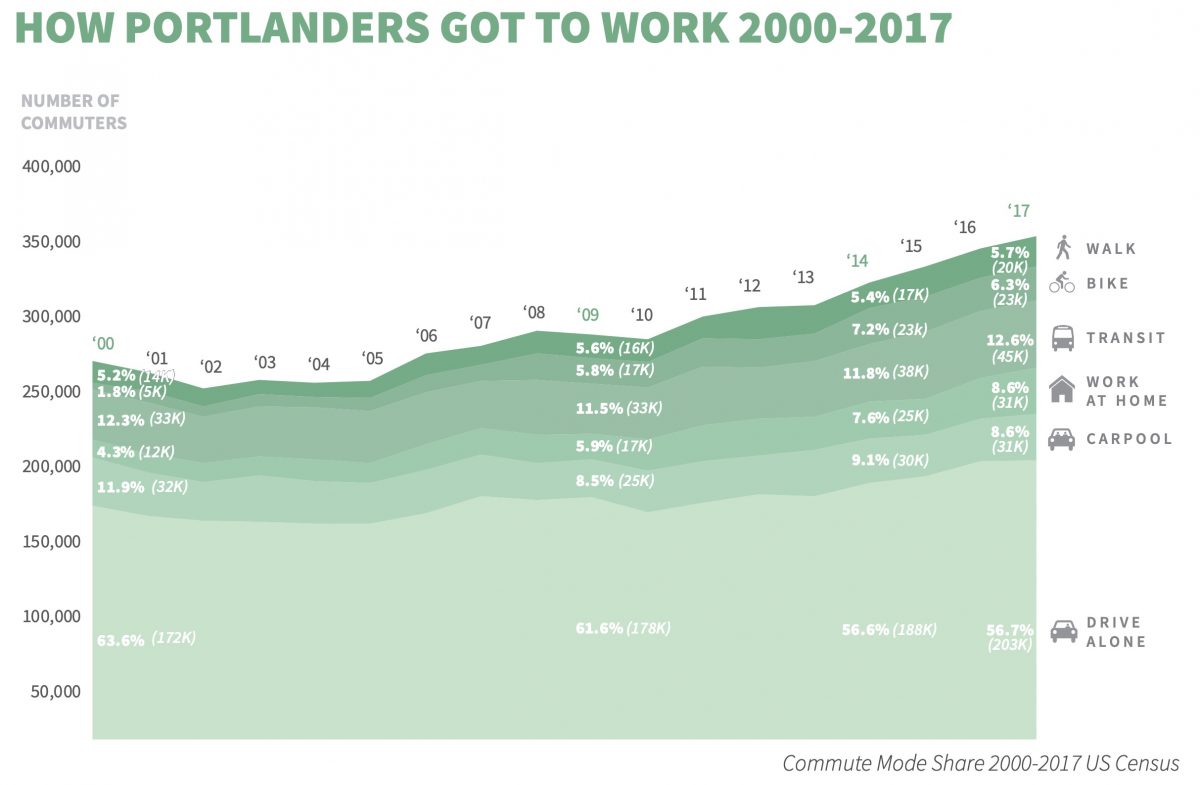

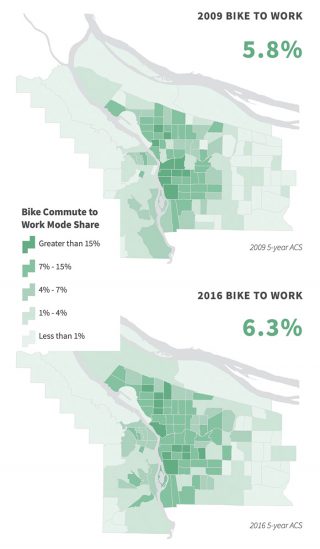

According to the US Census, the percentage of Portlanders who biked to work in 2009 (the year before Bike Plan adoption) was 5.8%. In 2017 that number had barely budged to 6.3% after hitting a peak of 7.2% in 2014. That’s the “extremely discouraging lack of progress” Gould referred to in her comments above.

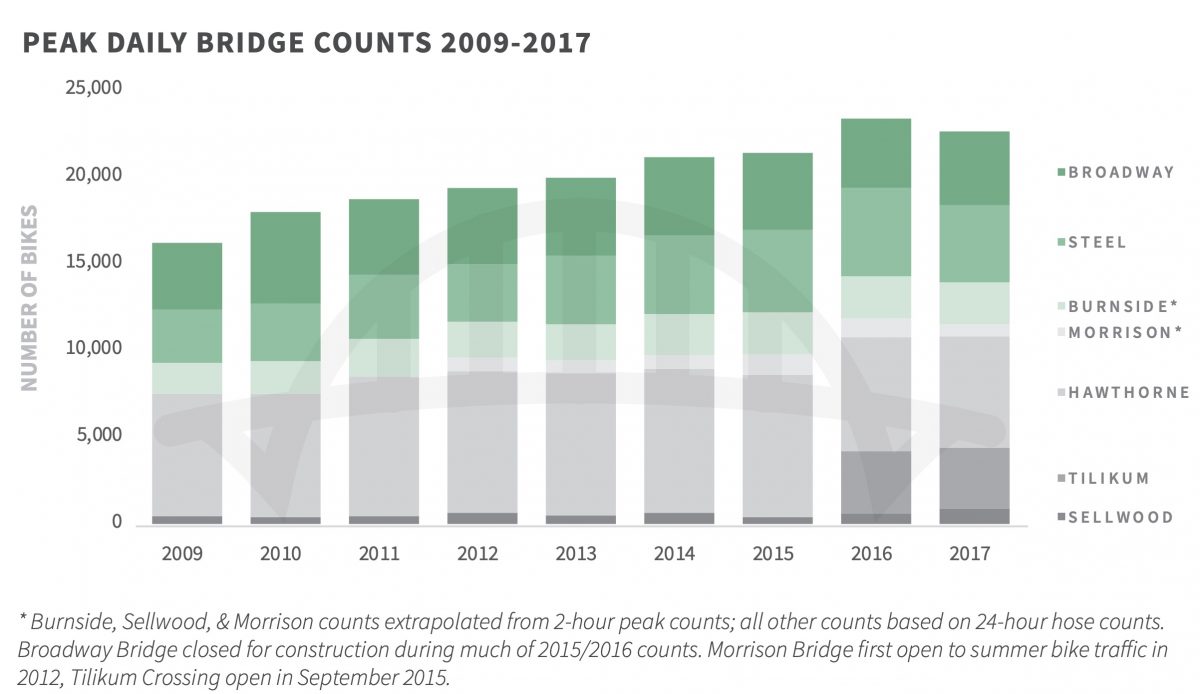

Another area of concern in the report came via a chart that tracks the number of bicycle riders who cross Portland’s main downtown bridges. This is one of PBOT’s most cherished stats and something they’ve used to tell the story of our success for many years. As you can see below, the total number of bicycle trips across the bridges ticked down in 2017 for the first time since records have been kept.

The Bike Plan was supposed to catapult Portland to the cycling promiseland. It outlined three main approaches to get us there: strong planning policies, ample infrastructure investments, and persuasive encouragement programs. We’re doing an OK job at all three. The problem is we’re not doing enough of it and much of our cycling infrastructure is so watered-down by the time it gets built that it fails to inspire the masses — or even the portion of the masses who remain “interested but concerned.”

(Photo: J. Maus/BikePortland)

While the Bike Plan is an important tool, we can only ask so much of it. That’s because much has changed in the past 10 years. When it passed in 2010, the discussion about how race and economic status impact bicycle planning — a.k.a. equity — was in its infancy. Since then, equity has become PBOT’s most important organizing principle. At a recent event, PBOT Director Chris Warner remarked that equity was his agency’s “north star”.

From an infrastructure standpoint, protected bike lanes were still rare in the United States when the Bike Plan was adopted whereas today they’re considered (by advocates at least) a bare minimum. “Build it and they will come,” was the prevailing mantra in 2010. Now we know it’s not that simple. There are myriad reasons why some people don’t ride — from fears of verbal or physical harassment and not having anywhere safe to ride or park their bikes, to fears of unfair treatment from police. That being said, a basic network of safe and connected cycling routes is a pre-requisite for reaching our goals (Commissioner Amanda Fritz referred to cycling as a “basic service” prior to voting for the plan back in 2010). And on that front, even Geller acknowledged at the meeting last night that, “We can do more.”

Advertisement

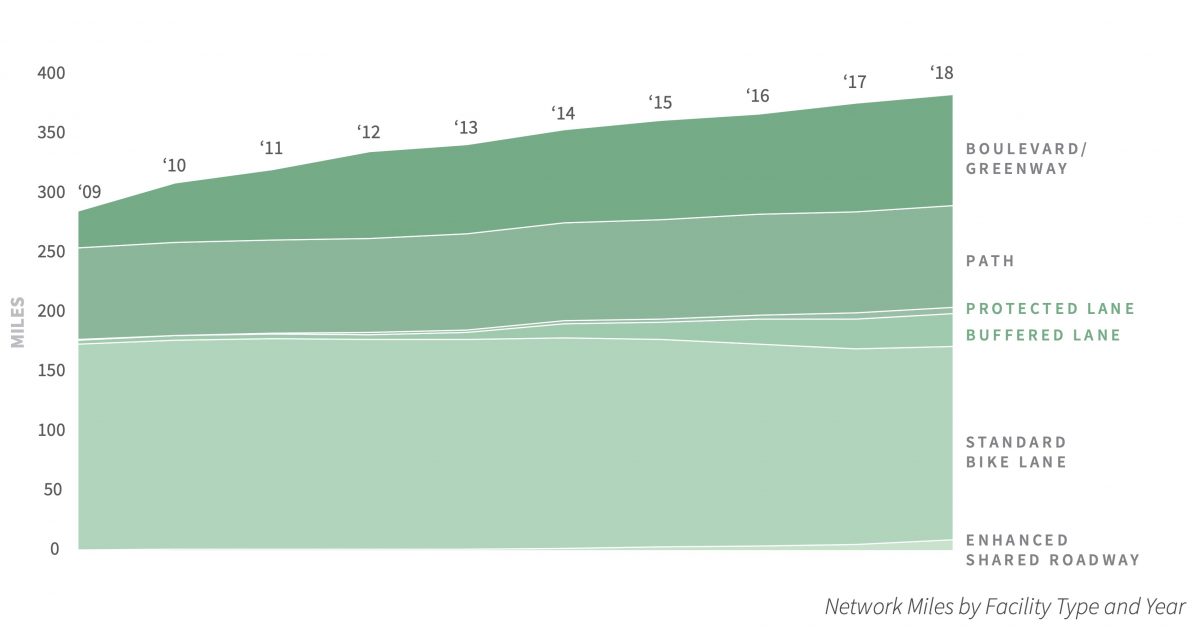

The 2030 plan identified 681 new miles of bikeways we needed to build in order to have a “cohesive, dense network”. In the last 10 years we’ve built just 99 miles of them (with 90 more miles funded for the next five years). The plan split the bikeway implementation strategy into three categories: “Immediate”, “80%” (where 80% of Portlanders would be within a quarter-mile of a “low-stress” bikeway), and “World Class”.

Geller says we’ve built and/or funded 58% of the Immediate and 80% network, but just 28% of the World Class network.

Beyond infrastructure, Portland’s increase in housing prices has had a major impact on cycling in the last decade. As many people have left the more bike-friendly core neighborhoods, they aren’t likely to bike as much when faced with longer commute trips and more stressful conditions. Maps shared in the progress report (at right) show a “decentralization of bike commuters” from the inner core to neighborhoods further out.

A bright spot in the progress report is how PBOT has stitched together our existing network and built more bikeways outside the central city. “In 2009, Portland’s bike network was sparse and highly concentrated in the inner neighborhoods of the East side,” the report reads. “Today, Portland’s bike network includes a much more dense array of neighborhood greenways and buffered or protected facilities there are numerous projects funded

for construction to bring this same connectivity to the neighborhoods east of I-205.”

Below is a look at 10 years of Portland bike network progress in the central city and citywide:

BAC member Iain Mackenzie told Geller Portland should look to Seattle for inspiration on how to guarantee more bikeways get built. Last week Seattle City Council approved a new policy that says if the Seattle Department of Transportation begins a major road project and chooses to not build a bike lane identified in the city’s bike lane, the DOT must bring the project to council and explain why.

“If Portland continues to grow as expected and new residents continue to drive at current rates, the transportation system will fail.”— from the report

Geller was receptive to the Seattle’s policy and he acknowledges PBOT must do more. “There remains a long way to go to reach Portland’s goals,” the report states. “If Portland continues to grow as expected and new residents continue to drive at current rates, the transportation system will fail. There is simply not room to add travel lanes without having a devastating impact on the form and character of existing and upcoming development.”

To get there, the reports recommends three approaches: develop stronger design guidelines for all new bike facilities that will attract riders of all ages and abilities, build more of the bike network as quickly as possible, and increase educational and marketing efforts to spread the awareness of cycling.

Given how cost-effective, popular, and beneficial to city life cycling infrastructure is, you’d think Portland could easily quicken the pace to our 25% goal. That might seem like the case from the outside, but within PBOT, staffers would be quick to point out what they see as major structural challenges. In the deflating conclusion to the draft report, PBOT details what they consider as three major challenges facing the future of cycling in Portland.

1) PBOT assumes the dedication of cycling space in existing right-of-way will always lead to a fight:

“Reallocating space in the right-of-way to implement all ages and abilities bikeways represents a change that requires political and public support The future of Portland’s bicycling culture depends on having strong political leadership, an active community of advocates, and an educated public that understands the importance of a multi-modal city and the tradeoffs associated with building out the network of a world-class bicycling city.”

2) PBOT says faster implementation of projects is expensive, takes more staff than they currently have, and is difficult given what they see as a lack of political and public support for bike projects:

“More expensive materials like concrete traffic separators, and sidewalk-level bikeways can be beyond the reach of typical bikeway capital improvement budgets.”

“PBOT is facing a shortage of staff availability to deliver these projects… This has created an immense backlog, making it extremely difficult to deliver projects on time and on budget.”

“There have been numerous cases of bikeway projects getting delayed for years or ending up with substandard facilities because the community and political support to make important tradeoffs was not strong enough.”

3) Changing existing behaviors is difficult, costly, and complicated:

“Convincing the public that bicycling is the safest, most convenient, and fastest option will take time, individualized marketing, and a dramatic change in Portland’s driving culture… it can also be very difficult to reach the public via traditional outreach strategies.”

Perhaps in the final version of this report that we see in front of City Council this fall, PBOT will include a rosier section on opportunities. Our city has the social, civic, and physical foundation to build a world-class cycling network already in place. What PBOT needs is the confidence to go forth and conquer. Hopefully this report helps give it to them.

Download the report on the City’s website (PDF).

— Jonathan Maus: (503) 706-8804, @jonathan_maus on Twitter and jonathan@bikeportland.org

Never miss a story. Sign-up for the daily BP Headlines email.

BikePortland needs your support.