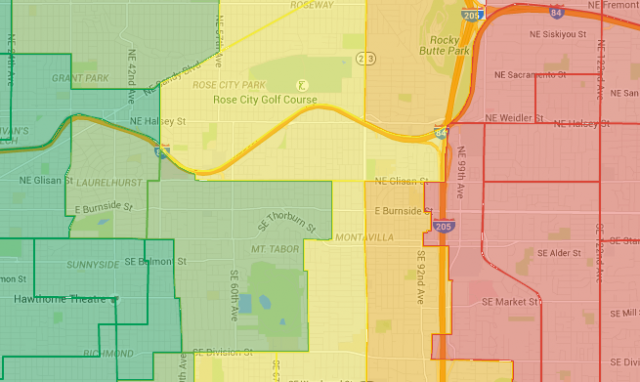

The paving and safety projects scheduled to be built with Portland’s proposed gas tax will be spread quite evenly across the city.

But votes on the gas tax definitely weren’t.

Of the 81 Multnomah County precincts in the City of Portland, only 19 tallied “yes” votes between 45 percent and 55 percent. In more than half of precincts, the vote on the 10-cent local gas tax, one of the country’s largest local fuel taxes ever approved by popular vote, was a blowout victory or loss by 20-point margins or even more.

The southeast Portland precinct that includes the Sunnyside neighborhood gave the “Fix our Streets” proposal its strongest margin in the city.

Disregarding two tiny precincts that had fewer than 100 voters (one of those voted yes, the other no) the “Fix our Streets” campaign was most popular in Precinct 4207, the Sunnyside district along Belmont Street and Hawthorne Boulevard on either side of Cesar Chavez Way. More than 69 percent of voters there supported it.

But the tax went down hard in every precinct east of Interstate 205. The further east, the more “no” votes it saw. In Precinct 5009 along the Gresham border (which also happens to be the eastern endpoint of the 4M Neighborhood Greenway that will be funded by the tax) only 20 percent of voters voted “yes.”

In all, 43 precincts voted “no” on the tax and 38 voted “yes.” But (unlike in national presidential elections, for example) every vote cast in the city has equal power, and precincts that voted “yes” generally had more residents. The tax slid into a 4-point victory (52.1 percent to 47.9 percent) on May 17.

Did votes split along income lines? By the amount of driving people do? By the perceived viability of alternatives to driving? By environmentalist or social justice sentiment? By trust in local government? Those are all possibilities but without exit polls, it’s hard to say.

Here are three two details worth noticing in the map above, though:

Advertisement

1) Southwest Portland said “yes” even though east Portland didn’t.

(Photos: J.Maus/BikePortland)

Two parts of Portland, outer east and outer southwest, were built mostly on Multnomah County roads, without sidewalks, in the era after 1959 when the city had banned multifamily housing from most areas, required on-site parking for commercial lots and avoided street grids. Decades later, all those decisions shape transportation habits, development patterns, housing prices and culture.

People who live in east and southwest Portland alike will tell you that their streets need a lot of work.

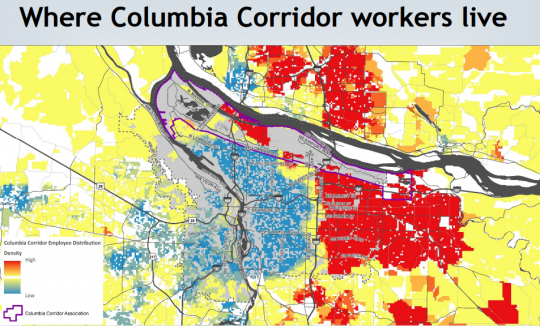

But last month, one of those two areas — the richer one — voted something like 55/45 “yes” on the gas tax and the other voted more like 70/30 against. What happened? One possibility is that it’s related to this map from a recent city study:

Southwest Portland is far from homogenously rich and east Portland is far from homogenously poor. But east Portlanders’ job market is hugely dependent on the city’s most important jobs center that’s virtually inaccessible except by car: the industrial and port land along the Columbia River. East of Interstate 205, transit lines and bikeways to central Portland and Gresham are scarce and mediocre, but they do exist. Transit and bike routes to the Columbia Corridor, though, basically don’t exist at all.

Southwest Portland, by contrast, can also be unpleasant to navigate on foot or bike, but it’s likely that more people there work in areas such as downtown that are relatively well-served by transit — or if they car-commute to Washington or Clackamas County, will be easily able to avoid the tax. Maybe that’s part of the reason the proposal did better in southwest.

2) Central Portland said “hell yes.”

If we assume that in the long run the gas tax will be a smart, money-saving and justice-advancing policy (as, presumably, most people in Portland government do), then we can’t ignore the single most important thing about this ballot measure: It passed.

Why did it pass? In part because of the 20 to 30 percent of east Portland voters who backed it despite their neighbors’ disagreement. In part because it broke 50 percent support in the southwest. But more than anything, it was because the proposal, which was very explicitly organized around the narrative that walking and biking should be safe and pleasant, racked up massive support in central Portland.

This support wasn’t limited to people who don’t buy much gasoline. Far more than half of people in central Portland drive to work, and almost every precinct in and around the central city saw more than 60 percent “yes.” Whatever the reason — some of it probably in self-interest, some of it probably cultural, some of it probably ideological — a gas tax that was once assumed to be politically impossible was successfully sold to overwhelming majorities in these neighborhoods.

Political action requires coalitions. Against odds, the gas tax built one.

Correction 3 pm: Due to a transcription error, an earlier version of the map and post reported an incorrect figure for inner northwest Portland, conflating it with the results from outer northwest. Since the revised figure is less surprising — inner northwest Portland voted overwhelmingly for the tax, like other central neighborhoods — we’ve deleted a section discussing this.

— Michael Andersen, (503) 333-7824 – michael@bikeportland.org

Our work is supported by subscribers. Please become one today.