We’ve explored this issue various times over the years, but you often hear people claiming otherwise so let’s share the information in a new way.

It’s relevant as the city gets ready to vote on a 10-cent gas tax that would go toward slowing the crumbling of Portland’s streets and improving their safety.

Who pays gas taxes?

Generally speaking, people who drive more pay more gas taxes. (No, this correlation is not perfect; vehicle fuel efficiency, which is largely a function of vehicle weight, matters too.)

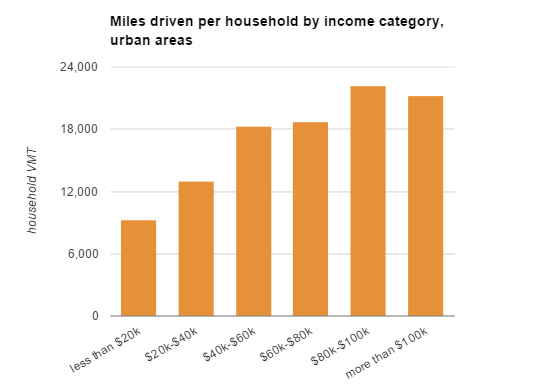

The data is very clear that higher-income households drive more.

This is less true in “dense urban” areas (which refers in this case to everything denser than “suburban areas”) than it is in suburbs, small towns and in the countryside. But it is definitely also true in cities like Portland.

Generally speaking, urban households that make $20,000 to $40,000 drive 39 percent more miles than urban households that make less than $20,000. Urban households that make $40,000 to $60,000 drive 41 percent more miles than urban households that make $20,000 to $40,000.

Advertisement

If you get more income than that, your household’s driving tends to level off. But urban households that make more than $100,000 still drive 16 percent more, on average, than urban households that make $40,000 to $60,000.

Portland’s median household income is about $55,000.

Does this mean that a gas tax is “progressive”? No, not necessarily. Progressivity means “poorer people pay less as a share of their income than richer people do.” Because the United States is heavily auto-dependent (including Portland and especially including many cheaper parts of Portland) lots of poor Portlanders are still spending money on gasoline.

Although many poor people own and use cars, poor people drive cars much less because poor people do less of everything, including getting around.

But there’s another factor here. Although many poor people own and use cars, poor people as a group drive cars much less because poor people do less of everything, including getting around. Households that make more than $100,000 a year travel 39 percent more miles than households that make $25,000 to $50,000. Households that make $25,000 to $50,000 travel 36 percent more miles than households that make less than $25,000. (These figures are from a federal analysis of the 2001 National Travel Household Survey.)

In the United States, being poor generally means not moving around much. Getting places costs money.

We’ll go out on a limb and say that immobility is not good.

So as voters think about the “progressivity” of a local gas tax, one question to ask is “Would this money be spent in a way that makes it easier and/or cheaper for poorer people to get around?”

We’ll see how well the backers of this ballot issue will be able to answer this question.

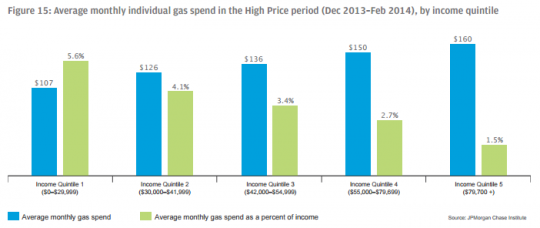

Update 1/26: In the comments, BikePortland reader Soren links to a study of 2013-2015 credit card data, showing that (a) yes, rich people drive much more than poor people, and (b) gas taxes are still a higher burden on poor people than on rich people as a share of income, because income inequality is more extreme than gas use inequality.

— Michael Andersen, (503) 333-7824 – michael@bikeportland.org

BikePortland can’t survive without paid subscribers. Please sign up today.