This is the third in a three-part series about the biking potential of the Lloyd District. Read the first two here.

This is the third in a three-part series about the biking potential of the Lloyd District. Read the first two here.

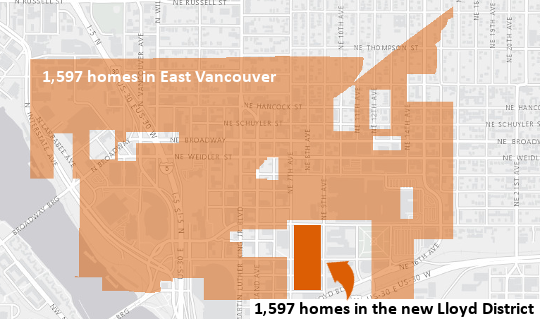

If 1,597 new homes were about to land in the space where, seven years ago, new homes in the Portland metro area would have been most likely to land, they would be the biggest news story in the area.

In the rural outskirts of east Vancouver (yes, that counts as Portland metro), beloved farms would be shutting down. Work crews would be widening intersections and stripping away street parking to make room for more turn lanes. For miles around, residents and businesses would be bracing themselves for traffic paralysis.

But in the next few years, 1,597 homes are lined up to land somewhere else instead: right in the middle of Portland.

The fact that this is happening with relatively little fanfare or controversy, at least not yet, speaks to the virtues of cities. The new apartments planned by American Assets Trust in the heart of the Lloyd District, both in the new Hassalo on Eighth project and its even bigger second phase, immediately to the south, represent 100 acres of exurban farmland that won’t be paved, miles of sewer mains that won’t be laid, thousands of police patrols that taxpayers won’t need to cover because all those households will be living on just eight city blocks.

When people move into Portland’s inner east side, about 20 percent of their trips around town are going to happen not in cars, as they would have in the outer suburbs, but on bicycles.

But the general lack of controversy over the Lloyd District’s building boom is built on something shakier, too.

It’s the assumption that when people move into Portland’s inner east side, about 20 percent of their trips around town are going to happen not in cars, as they would have in the outer suburbs, but on bicycles.

The assumption is reasonable. Portland’s history proves beyond a doubt that when the city builds bikeways, Portlanders use them. As we reported last week, Portland was so successful at building bikeways in the late 1990s that in the decade that followed, the city created 24,000 jobs for its residents without adding a single new car commute to its roads.

There’s every reason to believe that as it fills in, the Lloyd District could do something similar. But there’s a catch: the Lloyd District needs to stop being one of the hardest central east-side neighborhoods to bike in and out of, especially north and south.

Today, the local business group Go Lloyd estimates that 7.4 percent of commutes to the district happen on bicycle — not bad, but less than nearby neighborhoods and far below what’s needed.

To improve that ratio, the district needs to make its bikeways comfortable, intuitive and direct enough that thousands of the area’s workers and residents will choose to use them at least some of the time.

Local transportation experts agree that to make biking mainstream, the district needs, at the least:

1) A comfortable crossing of Interstate 84 to inner Burnside and Southeast

2) A comfortable bike connection north to Fremont, Alberta and beyond, with the gentlest slope possible

3) A direct and comfortable bike route west into downtown

4) A well-connected link to the east, where many of its workers live

Here’s the good news: the city has a detailed plan for the fourth item and is moving rapidly to plan the first three. The question for the future success of the Lloyd District is when and whether anyone will actually build them.

City eyes a major outside grant

(Photos: M.Andersen/BikePortland unless noted)

In 2009, inner north and northeast Portland, including the Lloyd District, had a chance to build a complete modern biking network all at once.

Metro applied for what was then a new federal program called TIGER grants. Its proposal would have brought in $38 million to build 40 miles of neighborhood greenways, plus raised bike lanes on Vancouver and Williams and a handful of buffered bike lanes.

The city said it would be enough to bring the quadrant’s biking rate from 15 percent to 35 percent.

Metro didn’t get that grant. One of the standout applications that did win in that first TIGER round: the Indianapolis Cultural Trail, now recognized as the country’s only connected downtown network of protected bike lanes and the force behind an economic renaissance for downtown Indianapolis.

Six years later, a city official said this week, Portland seems to be getting ready for a second try. Mark Lear, a funding expert with the Portland Bureau of Transportation, said Tuesday that the city is evaluating “a number of projects in the Lloyd District that could eventually be a future grant request, including a TIGER request.”

It’d be a bundle of biking and walking improvements that follows the path blazed by the city’s East Portland in Motion and Southwest in Motion plans. Lear said other money sources, including local ones like development fees, could be better fits than the federal grants — assuming the the projects can find support from the Lloyd District and its neighbors.

“PBOT over the next few months is going to be working aggressively with the district to help prioritize the most important transportation projects,” Lear said.

This is the city’s first public mention of this effort, and it’s great news.

Let’s help write the project list.

The Lloyd’s biggest leap

The keystone of a bikeable Lloyd District would also be the project that solves inner-east Portland’s biggest biking challenge: crossing Interstate 84.

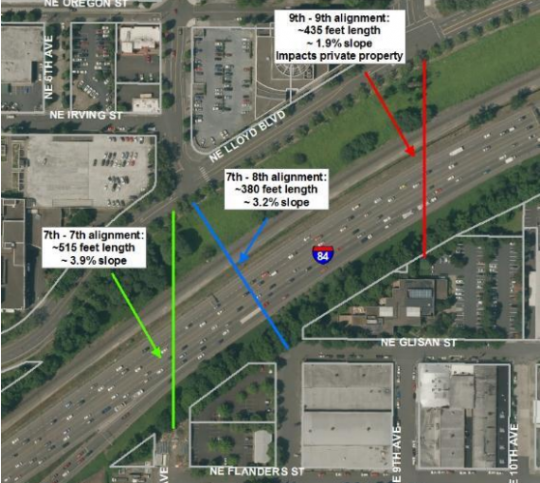

The obstacle: 380 to 515 feet of air across Sullivan’s Gulch, including a set of railroad tracks and seven lanes of freeway.

If a bridge were built without carrying cars or trucks, it would be tens of millions of dollars cheaper and the connection would instantly become the best north-south crossing of the freeway within city limits.

“It’d be a game changer,” said Carl Larson, engagement manager for the Bicycle Transportation Alliance. “I describe it as MLK for people walking and biking.”

“It’s not something that will build itself,” said Rick Williams, the former longtime director of Go Lloyd. “It’s going to be $15 to $20 million. But there’s high support for it.”

Where would the money come from? A price tag that big would require outside grants for sure. But as long as the bridge didn’t include cars, 100 percent of the local match could come not from the city’s precious general revenue but from system development charges — the fees the city charges developers to cover the cost of the new trips their projects create.

Portland doesn’t require SDCs to actually be spent near the developments that pay them. But since Hassalo on Eighth has already spent half a million dollars on transportation SDCs, and with other new Lloyd projects lining up to add to that total, there’s a strong case to be made that this would be the perfect way to spend them.

For Andrew Neerman, a resident of the nearby King neighborhood who serves as vice chair of his neighborhood association, the current options for crossing 84 on a bike in the area — Grand, MLK, 12th — stopped being options the day his son was born.

“It’s easy for me to ride alone, but in terms of taking a family ride down there, there’s just no way. I would never do that,” Neerman said. “I want to be able to ride from northeast to southeast with my baby safely. It’s just as simple as that. … If we’re ever going to achieve the mode share in the bike plan, we have to do projects like this.”

A neighborhood greenway north: Could diverters make 7th pleasant?

If a biking-walking bridge crosses I-84 at 7th or 9th avenue, the Lloyd District would never again be the district bikes avoid. It’d be the district that every bike trip between inner Northeast and Southeast Portland would want to go straight through.

There’s just one problem: which streets would all those bike trips use to get to the bridge?

Today, the stretch of Northeast Portland between Rodney and 28th is one of the biggest expanses of the city where there aren’t even any immediate plans for a single marked north-south bikeway.

Immediately north of the Lloyd, some people take 7th, despite busy rush hours and traffic islands that squeeze cars and bikes together. Some take 11th despite an awkward jog at Fremont.

The city’s official plan is to someday convert either the passing or parking lanes on 9th Avenue to bike lanes immediately west of Lloyd Center Mall. (Removing the extra passing lanes would also make 9th much more walking-friendly.)

North of Broadway, 9th would become a new neighborhood greenway running right into the middle of Irving Park, curving beneath this row of neglected lampposts, and continuing all the way to Dekum:

It’s an appealing vision. But there are problems.

Here’s one: stoplights. They cost a quarter-million dollars each, and a 9th Avenue greenway might need them at Fremont, Prescott and Alberta.

Here’s another: 9th Avenue through the Lloyd, though underused today, will get much busier if it shoulders most of the new auto traffic in and out of the Lloyd.

“There’s over 5,000 parking stalls that can be accessed off 9th Avenue,” said Owen Ronchelli, executive director of Go Lloyd. “We’ve got six or seven loading docks that come out of there with big trucks. We’ve got two bus lines on there. Garbage trucks and all of our major freight deliveries right now occur on 9th.”

Ronchelli was one of several people who said the Lloyd District’s landowners are firmly opposed to bike lanes on 9th Avenue.

Here’s a final problem with 9th: north of the district, it can’t make up its mind whether it’s going uphill or down.

Given that set of problems, Larson and the Bicycle Transportation Alliance have proposed an interesting alternative to 9th: 7th Avenue.

Unlike 9th, 7th Avenue already has full signals at each major street, plus a small commercial node at Knott. And here’s what 7th looks like from the side:

A final advantage of 7th, Williams noted: a bridge between NE 8th and NE 7th would not only be the shortest of the available options, it would run perpendicular to the freeway, creating an iconic advertisement for Portland’s bike-friendliness just as people round the bend into downtown.

There is exactly one problem with a bikeway on 7th. North of Broadway, it’s become a rush-hour alternative to Martin Luther King Boulevard for people in cars. North of the Lloyd, 7th Avenue carries 5,500 cars per day.

The city’s new target for a comfotable neighborhood greenway is 1,000.

Larson says the solution is simple: add traffic diverters to 7th that force rush-hour car traffic to use MLK, just like the city once forced traffic onto Division when it created a diverter at Clinton and Chavez.

“Its parallels to Clinton are a lot, actually,” Larson said. “It has the same treatments too, the circles. It has about the same traffic volume that Clinton did before there were efforts to put in some diversion. And it’s got a big road right next to it.”

Lloyd District landowners feel strongly that 7th Avenue should be the focus of future bike and foot traffic.

“There’s been lots of plans over the years,” said Williams. “7th Avenue has already been established through the Lloyd District as that north-south connector.”

The problem with diverters, of course, is the 4,000 car trips they would remove from 7th. Where would those cars go? What would nearby residents say?

For the city, the path of least resistance would be to leave 9th Avenue as it is south of the district, ask people biking to jog from 7th to 9th on Tillamook, and use cheaper rapid-flash beacons instead of actual stoplights at the bikeway crossings further north.

But Neerman, the King Neighborhood Association board member, said he thinks diverters on 7th wouldn’t be a hard sell.

“Most of the neighbors will buy in in Irvington and King for the simple reason that right now there’s a ton of cut-through traffic just trying to avoid MLK,” he said. “We have a full-on rush hour on 7th these days and there are a lot of Washington plates.”

Broadway: A business district waiting for a boom

Lined with parking lots, auto dealers and fast-food joints, inner Broadway rivals Sandy as Northeast Portland’s least Portland-y street.

But though the width that gave Broadway its name is currently devoted to three lanes of speeding traffic, it’s also home to the sort of businesses that will make life in the Lloyd District practical.

“What I think a lot of people on bikes don’t realize is that there’s so much good stuff on Broadway,” said Larson. “I live off Alberta and it doesn’t have anything useful. Broadway has real places to go to where you can buy useful stuff. There’s banks on Broadway. There’s a bookstore on Broadway. It’s really sad that it’s a business district with so few people, I think.”

Last year, Larson and BTA volunteer Chris Delaney spent months trying to gather support among Broadway businesses for changes to the street. In part, they hoped to advance a longtime dream for many Portlanders: a continuous protected bike lane from the Hollywood area to Portland State University.

(Image by Owen Walz)

“We heard their concerns loud and clear: they are concerned about people driving too fast on Broadway and about people not being able to walk across the street,” Larson said. “They get that that’s bad for their business, and they’re interested in solutions to those problems.”

What they didn’t embrace, Larson said, was a protected bike lane. He said many Broadway businesses hope the extra street space will be used for a streetcar line instead.

A Broadway streetcar line is currently on the city’s long-term vision, but that’s about it.

“I think people need to realize that Broadway doesn’t know what they want to do yet,” said Williams, the former Go Lloyd director. “Broadway is kind of where we were 10 years ago: in the planning phase. And I think the reason things worked so well in the Lloyd District was we all had consensus on specific things.”

Williams and Larson both agreed that if protected bike lanes are going to be built on Broadway and/or Weidler, the suggestion will need to come from businesses and landowners, not the city.

Both of them also agreed on one of the best things the city could do to build consensus about a protected bike lane on Broadway: finish upgrading the nearby one on Multnomah. That’d probably mean adding permanent planters or curbs and curving the bike lanes behind bus stops rather than forcing bike and bus traffic to mix.

“I talk to people on Broadway, some of them really get it and say they really like Multnomah, but some of them are sort of confused by it and say it looks really temporary,” Larson said. “Which it does.”

The crown jewel: a Sullivan’s Gulch path

(Photo: Ted Buehler)

The granddaddy of all missing links on Portland’s east side is the Lloyd District project that’s furthest from being built.

Just about everyone involved in the Lloyd District’s current rebirth seems to dream of an off-road bike path through Sullivan’s Gulch running west to the river and east to Gateway.

Lloyd EcoDistrict director Sarah Heinicke said it’d give thousands of East Portlanders a cheap and healthy way to reach jobs in the Lloyd.

One of them: American Assets Trust executive Wade Lange, a Portland native who regularly bike-commutes to the Lloyd from his home on NE 135th and said he’s been awaiting that path for many years.

“I think it would really make a big difference in terms of the viability of serious bike commuting happening in the outer reaches of the city,” Heinicke said.

But three years after Portland approved a detailed plan for the project, it’s essentially in deep freeze. Its project manager, Paul Smith, left Portland for a job in San Jose in 2013. (I ran into Smith at a conference last fall. He said he’d enjoyed Portland but prefers working in a city that actually has money to spend.)

The full path would cost an estimated $40 million, not counting about 600,000 square feet of property acquisition.

That’s expensive — it’s the same as the city’s grant application that would supposedly have brought all of inner north and northeast Portland up to a 35 percent bicycling mode share.

Even so, the trail would already be being built in small pieces, except for one thing: the biggest landowner by far is Union Pacific Railroad.

UPRR seems more open to the idea of working with the city to create a bike path south of Swan Island. But that’s in part because people already bike illegally on the so-called Cement Road through UPRR property; creating a legal route would actually reduce the railroad’s liabilities.

That’s not the case in Sullivan’s Gulch, currently used only by graffiti artists and a handful of urban campers.

Bringing the railroad to the table would require either huge wads of cash or something the railroad wants more, like removing some of the curves in its snaking route through the city.

Until the city or its allies in the state and federal government find one of those things, Multnomah Street will remain the Lloyd’s main biking link to the east, and the Lloyd will keep waiting for something more spectacular.

“I find myself staring out the window of the MAX whenever I take it, thinking, Oh, the trail could go there, you’d have to cut into that hillside, that’d be a little tight but you could make it,” Larson said. “Every time.”

The future of the District

(Image: GBD Architects via NextPortland.com)

Our first article in this series wrote about the Lloyd District’s potential to become the most bike-oriented high-rise neighborhood in the country. Our second wrote about its long, sad history of attempts to build itself around the automobile.

As we wrote at the end of the last piece, the plans now afoot in the Lloyd could fall apart. That might happen even if the area succeeds in making itself bikeable and walkable enough to prevent its streets from clogging with cars.

But if that happens, the list of people who’ll be surprised is getting longer every day.

Twenty years after its landowners made the baffling announcement that their plan to revitalize a struggling business district was to start charging for parking and investing in everything except the automobile, one entrepreneur after another is making bets on the future of the Lloyd.

The most recent announcement came yesterday, when the upscale fresh-food market Green Zebra Grocery announced that it’d become the long-awaited grocery tenant at Hassalo on Eighth.

For years, Hassalo’s developers have been planning to set aside hundreds of parking spaces for a larger grocery store in their underground garage, assuming that no grocer would ever sign a lease without guaranteeing plenty of free car parking.

It didn’t work. Every traditional grocer in town passed on the space anyway.

But Green Zebra CEO Lisa Sedlar, whose business model is built on short-distance trips, said Thursday that she’s asked only for “16 or 20 spots.”

“I would have gone forward with this store without any parking allotted to us,” Sedlar said.

She expects more than half her customers to arrive by transit, bike or foot — more than that if a bridge is built across I-84, NE Multnomah Street’s protected bike lanes are improved and half the bikes in Portland are streaming past her store.

“People think Lloyd District, ugh!” Sedlar said. “And we said, ‘No way, Lloyd District is coming on strong.’ It gets a 99 Bike Score for the neighborhood and the Walk Score is really high as well. … We just think the Lloyd is going to be it.”

— This in-depth series was brought to you by the bike-loving folks at Hassalo on Eighth, the Lloyd District development that is now leasing. We agreed on the subject of the series but they had no control or right to review the content before publication. Learn more about our sponsored content here and read all the articles in the series here.

Correction 3:30 p.m.: An earlier version of this post misspelled Andrew Neerman’s name.