(Photos: M.Andersen/BikePortland)

The Eastmoreland Neighborhood Association is trying to stop Portland from widening the four-foot door-zone bike lanes along four blocks of Woodstock Boulevard.

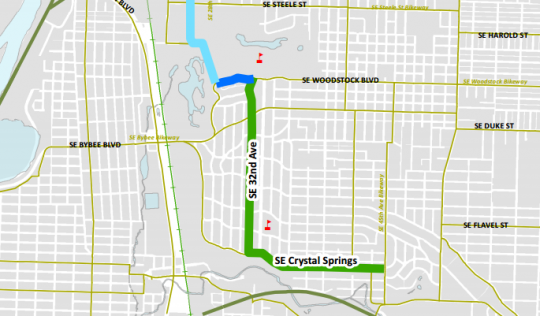

The four blocks would be a key link in the planned 20s Bikeway, the first continuous all-ages bike route to stretch all the way from Portland’s northern to southern border. But Kurt Krause, chair of the neighborhood association’s bike committee, said the benefits of a continuously comfortable route aren’t worth the costs of removing curbside parking in front of seven large houses that overlook the Reed College campus across the street.

All seven houses have private driveways and garages on their lots.

“The biggest problem, I guess, is just for deliveries, for repairmen, for things like that,” Krause said.

Tradeoffs for roadway space

The city’s current plans call for creating a five-foot curbside bike lane on each side of Woodstock with a two-foot striped buffer.

But there’d be no room for that on the current street without removing the one lane of parking.

“When they have their Thanksgiving dinner, they will not be able to have their family get to their house very easily — that was the example given by one family.”

— Robert McCullough, president of the Eastmoreland Neighborhood Association

A visit to the site last week showed that there were indeed a handful of cars, not obviously associated with the homes’ residents, parked along the south side of Woodstock Boulevard. (There is already no curbside parking along the north side, next to Reed’s campus.)

Two nearby residents described themselves as pro-bike in general but said they’d prefer to keep the street parking.

“If I clear out my garage, I’ve got two, three, four, six, eight cars here,” conceded Tyler Stevenson, who was washing a car in the driveway of one of the houses, where he lives as a tenant. Still, Stevenson said, “having the parking for the public is important.”

Stevenson said that cable or gas company drivers are sometimes forbidden from parking in private driveways. He added that campus events often lead to people using the curbside parking on Woodstock, which leads many guests of people in the homes to park on Moreland Lane, the narrow street behind the homes.

Cindy Simpson, whose home faces Moreland Lane, confirmed this.

Simpson’s driveway was one of the few on the block that was full when I stopped by on a Monday afternoon. It holds four cars:

Simpson said that’s because her daughter’s family shares the house with her and her husband. She said they never park cars in their garage.

“We have storage, you know,” she said.

“I’m all for bikes — I like sharing the road with them,” she added. “I think the bike lane is huge already. And I think it’s a waste of money when they could be paving the roads.”

(In our conversation, I told Simpson that I thought the bike lane was actually the minimum width, but I was wrong; it’s actually narrower. The current national minimum standard is four feet for a curbside bike lane and five feet for a door-zone lane. Both of Woodstock’s bike lanes are four feet wide.

According to a 2014 study, 94 percent of people bike in the door zone of a four-foot door-zone bike lane. With a five-foot door-zone bike lane, this falls to 91 percent.)

“I’m able to live with it however they do it,” Simpson said in conclusion.

Advertisement

City shouldn’t remove parking without studies to justify it, neighborhood official says

Robert McCullough, president of the Eastmoreland Neighborhood Association, called his own opposition to improved bike lanes “mainly a public involvement question.”

He said it was based on objections from nearby residents about the lost street parking.

“When they have their Thanksgiving dinner, they will not be able to have their family get to their house very easily — that was the example given by one family,” McCullough said.

In the face of conflicts like this, McCullough said, the city should be consulting “best practices” before any such changes.

“There’s a whole set of traffic rules and regulations and studies,” he said. “We don’t do much of that in Portland.”

McCullough said he isn’t familiar enough with transportation policy to offer examples of what would or wouldn’t constitute a “best practice” on parking conversion.

McCullough also serves as president of the Southeast Uplift coalition of neighborhood associations, an organization that he’s helped rally to action against unregulated Airbnb rentals and the city’s calculations for a new “street fee.”

McCullough has also been one of the more vocal critics of many aspects of the 20s Bikeway since its planning process began. Under his leadership, the Eastmoreland Neighborhood Association has persuaded the city to reroute the bikeway away from Southeast 28th Avenue south of Woodstock, where parking removal would have been required, to its current route onto Woodstock and 32nd instead. EPN also persuaded the city not to add speed bumps to 32nd Avenue south of Woodstock. That street is expected to become part of a new neighborhood greenway connection to the Springwater Corridor at the south end of the 20s bikeway.

“The reality is that this is exactly what we envisioned for neighborhood associations to do in 1975 when we set it up,” McCullough said. “The right answer always is to involve everyone.”

Street could be worse, two local bike users say

Krause, McCullough’s counterpart on the neighborhood bike committee, said people who say the city can’t increase the use of bicycles without upgrading door-zone bike lanes like Woodstocks “certainly have a point.”

“I’m a bike rider myself, and I know those substandard lanes do cause problems and it’s difficult,” Krause said. “But you can make it on the 4-foot lane. It’s not impossible. I’d like to see them not do it. But then it seems as though we’ve sent letters and spoken out at meetings and had face-to-face with [Project Manager] Rich [Newlands] and other things, and nothing seems to really move them from their stance.”

Though Krause said he “would like to see wider bike lanes,” “I just don’t see it as having enough payoff to ban parking on the one side.”

Colin Stacey, a nearby resident pedaling home from work in Woodstock’s bike lane last week, said he’s all for biking improvements, up to and including removing the parking.

“I tolerate some pretty bad conditions,” he said, smiling ruefully. “I just came from Northwest through the Pearl. It’s terrible.”