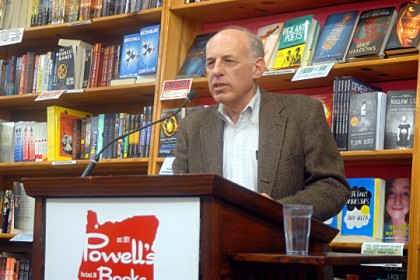

(Photo: Mark McClure)

Why does Portland require every new house to have a driveway big enough to fit two cars?

Why do we forbid most lots from having two separate dwelling structures unless one is 25 percent smaller than the other and has a roof with an identical slope?

Why do we ban second kitchens within a single home unless the owner essentially pinky-swears that only one household will be living in the building?

In a city where a chronic shortage of housing in walkable and bikeable areas has driven prices up and up, driving major changes in the culture, these aren’t trivial questions.

The most familiar answer to all of them is one of the most-used words in urban zoning: “compatibility.” But what exactly does that mean?

In his book Dead End, a political history of the suburbs, transit and biking advocate Ben Ross takes a close look at a vague word that shapes our cities one neighborhood association meeting at a time. From page 152:

Developers and nimbys, although everyday antagonists, share a common interest in the prestige of the neighborhood, and both use words as tools to that end. One party directs its linguistic creativity into salesmanship. Row houses turn into townhomes; garden apartments grow parked cars in the gardens; dead ends are translated into French as cul-de-sacs. The other side, hiding its aims from the world at large and often from itself, has a weakness for phrases whose meaning slips away when carefully examined. …

A tour of this vocabulary must begin with compatibility. The concept is at the heart of land-use regulation. In the narrow sense, incompatible uses are those that cannot coexist, like a smokehouse and a rest home for asthmatics. But the word has taken on a far broader meaning. …

The key to deciphering this word lies in a crucial difference between compatibility and similarity. If two things are similar, they are both similar to each other, but with compatibility it is otherwise. A house on a half-acre lot is compatible with surrounding apartment buildings, but the inverse does not follow. An apartment building is incompatible with houses that sit on half-acre lots.

Advertisement

Compatibility, in this sense, is euphemism. A compatible land use upholds the status of the neighborhood. An incompatible one lowers it. Rental apartments can be incompatible with a neighborhood that would accept the same building sold as condos. An apartment house and a ten-room mansion are both incompatible with an older subdivision of small expensive homes: the one because apartments are inferior to houses; the other because its yard, overshadowed by the structure, fails to manifest the conspicuous waste of land that gives such areas their special cachet.

The euphemism is so well established that the narrow meaning has begun to fall into disuse. Neighbors who object to loud noises or unpleasant odors just lay out the specifics; incompatible has come to mean “I don’t like it and I’m not explaining why.”

That’s from Ross’s chapter “The Language of Land Use.”

It’s a provocative take, though no harsher than the language we’ve heard in the last few years from some Portlanders discovering that their compatibility concerns won’t prevent new buildings in their neighborhood. And Ross, who lives and advocates in suburban Washington, D.C., is responding to slightly different dynamics than the ones we have in Portland, where everything is now shaped by the torrent of demand for homes in the parts of town best suited to low-car-life.

Still, it seems worth asking, every time we use the word “compatible” or allow someone else to do so, whether the values it implies are actually ours.

At least when it comes to driveways.

— The Real Estate Beat is a regular column. You can sign up to get an email of Real Estate Beat posts (and nothing else) here, or read past installments here. This sponsorship has opened up and we’re looking for our next partner. If interested, please call Jonathan at (503) 706-8804.