(Photos: M.Andersen/BikePortland)

While Portland prepares to block increased development along parts of TriMet’s newest MAX line, a group of residents further down the Orange Line say they’re welcoming more density with open arms.

Their dream, they say, would be to use three-to-five-story apartment buildings and clusters of new small houses to turn their corner of unincorporated Clackamas County — the last stop on the new MAX line — into a bustling but more nature-rich alternative to Southeast Division Street.

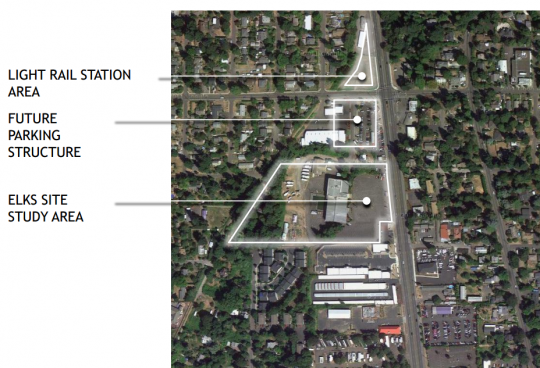

Though they hope to spur changes up and down McLoughlin Boulvard, the key to the plan is a 5.7-acre Elks Club site that sits between McLoughlin and the six-mile Trolley Trail multi-use path that serves as a bike route in the area.

Their proposal: cutting the area’s minimum residential auto parking requirement (it’s currently 1.25 spaces per unit) and allowing up to 60 housing units per acre within a quarter-mile of the SE Park Avenue station. In order to build at that density (or maybe a bit higher), a developer would guarantee to set aside some of the private land for natural areas.

“It seems like it would be a lightning rod that could catch some of the housing Portland is failing to build,” said Joseph Edge, 35, one of the organizers of the effort.

Bringing back commerce

Three members of Oak Grove’s unofficial neighborhood association — members of the McLoughlin Area Plan Implementation Team that’s working to rezone and rethink the area — were hanging out on the Trolley Trail just behind the MAX station as I pedaled up.

Chips Janger stuck out a hand.

“Welcome to our turf,” he said.

Janger, his colleagues say, was the mastermind of a deal that made natural areas part of the design of what will be TriMet’s southernmost MAX stop when it opens in September. Years later, he’s proud to be finally looking over the results: about half an acre of trees, scrubs and grasses in a restored gully between the trail and the new TriMet parking garage.

“This was all used car lots, parking lots, all this stuff,” says Janger, 58. “Our whole purpose is to restore an area that’s been degraded over the last 50 years.”

Advertisement

His colleague Eleanore Hunter, 56, explains that back when the Trolley Trail was an actual electric trolley line — the urban area’s first, she says — Oak Grove was a major destination.

“This was a hoppin’ place to come,” she said. “The jukebox joints, the nightclubs.”

No more. McLoughlin has grown into a busy suburban thoroughfare, but its auto-oriented storefronts are so utilitarian that when this group of neighborhood organizers held their first meeting, they couldn’t think of a single place to gather, sit and talk.

“We ended up at the McMenamins in Oregon City,” Hunter said.

Three reasons developers might choose Oak Grove

Why would a mixed-use developer make a big bet on the Park Avenue station area? Oak Grove advocates make a few arguments.

First: unlike some Portland neighborhoods, they say it’s eager for change. Zoning laws in the area allow any sort of use.

“With the exception of the density cap on residential zoning, it’s very flexible,” said Edge. “If you didn’t want to get a fight, then you might come here.”

Second: the combination of the Orange Line and Trolley Trail, along with a possible future bike-walking bridge to Lake Oswego, will make it easy to get around without a car in the area.

“We predict that there’s going to be this dramatic shift,” Hunter said. “There are these wonderful small starter homes in these close-knit communities that are within walking distance of the station.”

“We’ve worked real hard to make this a transportation complex,” said Janger. “The Trolley Trail part, the bike part, is as important as the light rail station. We think this is such an important arterial.”

A few of Oak Grove’s oldest homes, in fact, face their front doors directly onto the Trolley Trail. It’s a relic of the time when the area’s most important transportation was the streetcar that once whistled past these front doors and into the city.

And that’s the third reason Janger, Hunter and Edge think it makes sense for their neighborhood to become a suburban hub for low-car life: that’s the sort of lifestyle that built their neighborhood in the first place.

“Oak Grove and the Elks Club were created the last time there was light rail here,” Janger said. “And now we’re back, baby.”

— The Real Estate Beat is a regular column. You can sign up to get an email of Real Estate Beat posts (and nothing else) here, or read past installments here. This sponsorship has opened up and we’re looking for our next partner. If interested, please call Jonathan at (503) 706-8804.