(Photo: J.Maus/BikePortland)

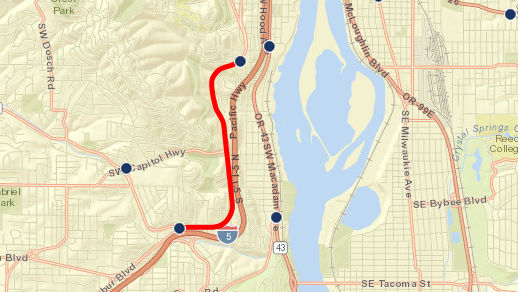

Converting one northbound traffic lane on 1.9 miles of SW Barbur Boulevard to two protected bike lanes with sidewalks would apparently prevent unsafe weaving during off-peak hours without massive impacts to morning traffic.

That’s one conclusion from data released Friday that analyzed changes to people’s driving habits during construction work on Barbur this summer. A repaving project had temporarily closed one traffic lane in each direction.

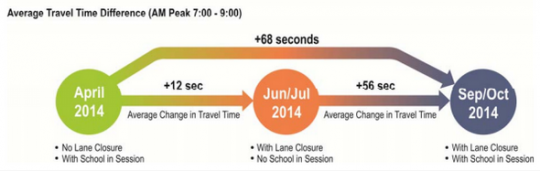

The study, led by the Oregon Department of Transportation because Barbur is a state highway, found that temporarily narrowing Barbur to two lanes at this point had added 68 seconds to the average northbound rush-hour trip.

However, that delay — a slowdown of about 23 percent for the length of this 1.9-mile stretch of road, from about 30 mph on average to about 24 mph — apparently bothered almost no drivers enough for them to switch routes.

(Image: Portland State University PORTAL system)

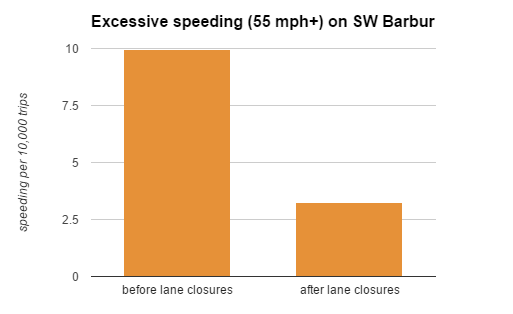

Moreover, the proportion of northbound drivers who had been speeding at 55 mph or faster through this stretch during non-rush hours — often by weaving rapidly through midday or early evening traffic — plummeted 68 percent during the lane reduction, according to the same data set used in the study.

(Data via ODOT study. Chart by BikePortland.)

Southwest Neighborhoods Inc., Lewis and Clark College, the City Club of Portland, Oregon Walks and the Bicycle Transportation Alliance have all urged for study of a redesign of this frequently deadly stretch of road, which last year accounted for three of the city’s 35 traffic fatalities.

Barbur also happens to be the only relatively flat connection between most of Southwest Portland and the rest of the city. It currently forces people biking and driving to merge into the same 45 mph travel lane as they cross two narrow bridges, or else to ride up a ramp onto a 3.1-foot-wide “maintenance walkway” that also functions as the closest thing to a sidewalk.

But ODOT last year rebuffed calls to redesign Barbur, citing “strong objections from stakeholders.” (As far as ODOT’s records showed, this was apparently a reference to one key stakeholder: the Portland Business Alliance, which is the region’s chamber of commerce. Seventy-nine percent of input the agency received on the issue was actually in favor of a road diet study.) The state agency publicly predicted “unacceptable impacts” on future travel times and neighborhood traffic if one of Barbur’s northbound lanes were closed to cars and trucks.

After much debate, ODOT agreed to this summer’s study not of an actual road diet but of changes to traffic patterns during the road work.

The results offered some ammunition for people on each side of the argument.

Weekday morning traffic delay: 68 seconds over 1.9 miles

On one hand, the study found that the road work did indeed slow traffic: by an average of 68 seconds (30 percent) for northbound traffic on Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday mornings. Closures added as much as 108 seconds (48 percent) during the busiest half-hour of those mornings, which was 8:15 to 8:45.

This was somewhat heavier than expected. Last year, estimates from two different software programs had predicted traffic delay of only 11 to 34 seconds (5 to 15 percent) in the event of a road diet.

Traffic is typically lighter on Mondays and Fridays, so rush-hour travel didn’t slow as much on those days. ODOT chose to omit these days from their study; it’s not clear why. ODOT also omitted data from the fastest 15 percent and slowest 15 percent of road users, considering them outliers.

Both of these choices had the effect of increasing the average travel delay reported in ODOT’s study. Had the agency merely averaged rush-hour speeds across all weekdays, it would have found that road work led to a 20-second (9 percent) average delay for northbound traffic.

Advertisement

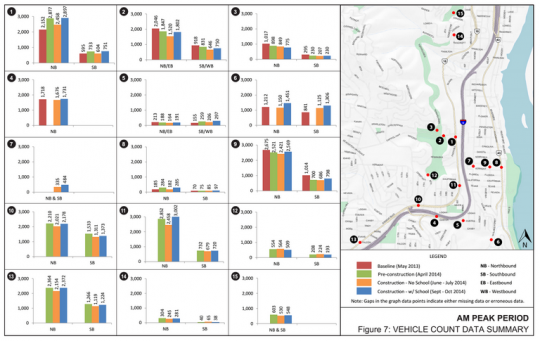

Little sign of traffic diversion

(Image: ODOT)

On the other hand, ODOT’s study found that very few people seemed to bother with using other routes to avoid the construction zone.

This had been a major concern for some neighborhood advocates. ODOT had predicted that 5 to 20 percent of Barbur traffic would switch onto other streets. No such shift was observed, however; traffic counts on Barbur were virtually unchanged during comparable periods, as were those at 12 nearby locations that might have been alternative routes.

Another significant discovery wasn’t mentioned in ODOT’s initial report but was visible in an analysis of the same data: speed data suggested that the biggest safety benefit of a road diet — preventing extreme speeding by making it impossible for the most reckless road users to weave their cars back and forth between lanes — worked well during the June-July lane closure. The percentage of cars observed moving faster than 55 mph fell from 10 per 10,000 to 3 per 10,000.

What’s more, all of the cars moving faster than 55 mph during the lane closures were doing so between midnight and 7 a.m., presumably because there were few other cars on the road. In April, when all four lanes of Barbur were open, more than half of extreme speeders were doing so between 8 a.m. and 9 p.m.

The speed tests were conducted using devices that detect Bluetooth signals, so they represent only a subset of Barbur traffic: for the pre-construction period, the data came from 13,032 Bluetooth signals captured over 30 days; during construction, from 15,457 Bluetooth signals captured over 31 days. (You can explore the data for yourself here.)

Five reasons traffic slowed; only one would apply to permanent redesign during rush hour

(Image: Google Street View.)

Why did rush-hour traffic move more slowly during construction? It’s hard to know from the data, but it’s presumably from some combination of these five factors:

1) Congestion during rush hour. Some of the change was probably due to two relatively crowded lanes merging into a single one.

2) Auto drivers getting stuck behind bicycle riders. For part of construction, people in cars and on bikes merged into a single lane, so drivers may have had to queue up behind bicycle riders. This wouldn’t happen if bike lanes were added.

3) Less weaving. With only one lane in each direction, people wishing to speed couldn’t weave between lanes to do so. This probably had little effect during rush hours, when Barbur is already crowded enough to prevent speeding, but a larger effect for the rest of the day.

4) Lower speed limit. During construction, the posted speed limit was cut from 45 mph to 35 mph, with warnings of increased enforcement and higher penalties. This might or might not apply in the case of a permanent redesign.

5) People in the work zone. The presence of road workers probably helped slow traffic, ODOT spokesman Don Hamilton wrote in an email Monday. This wouldn’t apply in the case of a permanent redesign.

One argument the Portland Business Alliance had mounted against a road diet was that the extra lane of Barbur is needed as an escape valve in case of a major blockage on Interstate 5. However, no such blockages happened during any of the periods studied.

“Therefore, we did not have an opportunity to measure the impact from such an event,” Hamilton wrote Monday.

BTA calls for separated lanes and sidewalks

(Rendering: Owen Walz)

In a blog post Friday, the Bicycle Transportation Alliance said Friday’s study “validates” the community’s “call for safety.”

“Their preliminary numbers on delays suggest that there’s no reason not to do the road diet,” BTA Advocate Carl Larson said in an interview Monday. “There was predicted lots of diversion, which is not what we’re seeing.”

Larson noted that this study looked only at the impacts of a work zone, not of a permanent road redesign.

“This is really preliminary information that we’ve been given, and it suggests, from what we understand, a road diet would go even more smoothly than the construction zone did,” Larson said.

He also questioned whether it even makes sense to be worrying about traffic delay on a street that has seen so many fatalities and injuries of people in cars and on bikes.

“We’re just focusing on trying to make the road safer,” Larson said. “From our perspective, you can’t pit safety against convenience.”

The BTA’s annual New Year’s Day ride will focus on their call to fix Barbur. The organization has also circulated a petition calling for “immediate construction of new physically separated bike lanes and sidewalks on SW Barbur.”