Portland is thick with indie bike frame builders. But the most audacious bike-design entrepreneur in town is focused on everything except the frame.

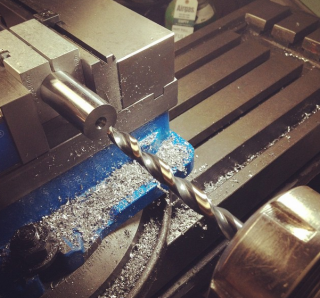

Ringed on three and a half sides by his tiny metal fabrication studio — a sort of blue-collar cubicle inside ADX, Southeast Portland’s coworking facility for people who make stuff — David Lewis described the product he’s slowly trying to design from the gears out.

“It’s an American bicycle that’s affordable and ready to ride,” Lewis said. “I don’t know what that bike looks like yet.”

The 37-year-old founder of Veteran Bicycle Co. just got his machine manufacturing certificate this fall. But he’s about to head into his second year of trying to come up with completely new and lower-cost ways to design and manufacture any and every part of the bicycle.

It’s a process whose fundamentals were, he noted, invented almost 140 years ago.

“It was the 1880s, the boneshaker, I think,” said Lewis, who named his young bikebuilding startup after his 11-year career in the U.S. Army and Army Reserve. “Essentially, what we have today is the same thing. … You still sit on a bike with two wheels and a handlebar right here and steer the same way and pedal the same way. And nobody’s tried to challenge that yet.”

Lewis, born in Binghamton, N.Y., doesn’t see why that person shouldn’t be him.

Since leaving the military, Lewis has trained at Portland’s United Bicycle Institute and worked at Chris King Components. And though he might not end up rethinking the form of bikes entirely, he says his competitive advantage in his experiments is that the money in the bike industry remains focused on high-end solutions that prioritize performance over cost.

“What works in racing doesn’t work on a bike that’s cheap,” he explains. “We’re going through the process of reinvention right now for the drive train of a bicycle. … If you wanted to do anything else with gears, you’d have to buy these special things from Germany called a Pinion gear. That’s great and all for enthusiasts but there’s no way that the normal person can afford that.”

It’s just an example. But he’s thinking about ways to use axle widths, dropout spacing or integrating hub bearings into the frame as ways to “liberate bicycle drivetrain design and construction from what I feel is the dead weight of the derailleur.”

Advertisement

And he’s also searching for procedural simplifications such as, he says, “replacing traditional silver-brazing of cable guides and bottle bosses with a less expensive alternative using silicon bronze and a TIG torch. This also eliminates the need to rinse flux out of the joint with water, saving a step and also preventing a source of rust.”

His long-term goal is to work out a manufacturing process that would let him personally build 30 bikes per month while keeping his labor costs to $100 per frame. The bikes might retail in the $500 to $600 range and include accessories.

Other low-cost manufacturers, Lewis said, are “trying to sell you a $500 bike that’s really an $800 bike in disguise.”

“What’s happening now is conventional wisdom: import the bike and then sell a bunch of crap to the people who buy it — I don’t like that,” he said. “I want to make bikes that are ready to ride as soon as the person buys it. It’s got fenders for they can ride in any whether. It’s got lights. That’s not optional. It’s got a bell. It’s got a way to carry stuff.”

Though he has no apparent ambition of great wealth, Lewis is ambitious about bringing new ideas into bikemaking.

“I’m not necessarily a homebrewer who wants to be a craft brewer,” he says, referring to Portland’s bike-building scene. “I want to be a responsible Budweiser.”

To that end, he’s been saving cash and gathering skills as part of a Mercy Corps Northwest program that will give him a micro-grant at the end of this year. He plans to use it to buy a lathe and start manufacturing his first product: dummy axles.

“For shops, they are a commodity item that there are never enough of, and for consumers it will function as a shipping plug to protect dropout spacing during shipping frames for touring,” Lewis said. “My versions will be made of hardened tool steel and should last forever.”

Lewis, a bike user since his days as a paperboy, says he’s “not a salesman.” But he’s determined to find a way to bring his unorthodox ideas about bike manufacturing to market.

“I’m in the middle of trying to figure out how to turn this into a viable business,” he said, leaning over his workbench. “But I don’t give up, that’s for damn sure.”

Correction 11/14: A previous version of this post incorrectly described Lewis’s ideas about metal joining and drive trains.