N Rosa Parks at Michigan.

(Photo by J. Maus/BikePortland)

A new traffic diverter at North Michigan Avenue and Rosa Parks Way seems to be successfully preventing north-south car traffic from spilling onto Michigan from Interstate 5, recent city bike counts show.

That was the city’s intent when it agreed last year to install the diverter in order to hold down traffic on the neighborhood greenway there.

“From I guess Holman to Rosa Parks it has gotten a lot better,” said Noah Brimhall, a Piedmont neighborhood resident and an advocate for the diverter, in an interview Tuesday.

(Photo by J. Maus/BikePortland)

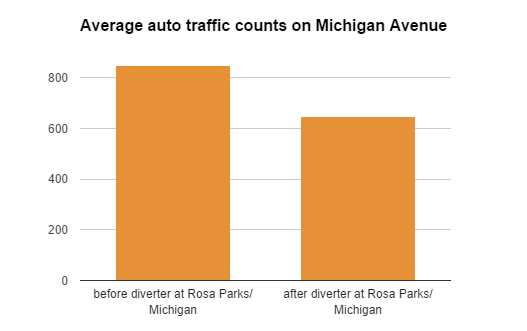

Since the diverter went in last fall, the city’s counts for auto traffic on Michigan south of Rosa Parks have fallen by an average of 25 percent from prior observations:

All eight traffic counts on Michigan showed a decline after the diverter went in. In the block immediately south of Rosa Parks, auto traffic dropped 45 percent.

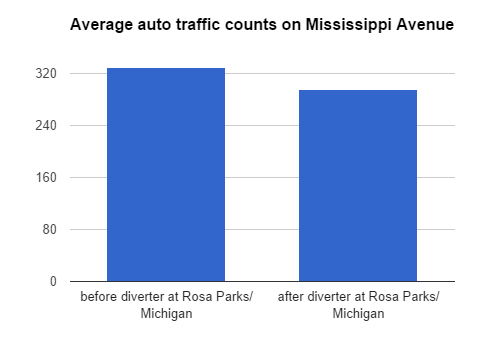

Traffic even seemed to fall on nearby Mississippi Avenue — by 10 percent on average, suggesting that through traffic remained on the freeway or other routes rather than simply shifting one block further east.

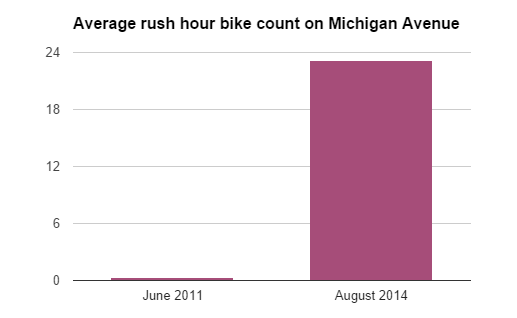

The drop in auto traffic, however, hasn’t yet led to a major surge in bike traffic on this neighborhood greenway, at least in absolute terms. The city’s north/south bike counts on Michigan increased from almost zero in 2011 to an average of 23 bikes in both directions during rush hour in 2014.

By contrast, the relatively comfortable east/west freeway crossings on Rosa Parks and Ainsworth drew bidirectional rush-hour bike counts in the 80s, an apparent sign of heavy demand for comfortable bikeways on major arterial streets.

Paul Anthony, chair of the Humboldt Neighborhood Association south of Rosa Parks, said his organization strongly supports biking improvements such as the Michigan Greenway “for obvious reasons” including reduced car traffic to Portland Community College and the economic benefits to retailers along Killingsworth and Mississippi.

“Frankly,” he said in an interview Tuesday, the rush-hour bike counts on Michigan were “disappointing.”

Advertisement

Brimhall, the Piedmont neighborhood advocate, said most people heading north and south by bike simply take the nearby wide bike lanes on Vancouver and Williams.

“A lot of people in this neighborhood and North Portland in general just tend to gravitate toward that street,” he said. “The reason I go over on Michigan is to get to my son’s school.”

He thinks the crossing at Killingsworth has poor lines of sight, and that poor pavement on Michigan south of Killingsworth makes the neighborhood greenway “less welcoming.”

Anthony agreed.

“Michigan’s surface is very, very poor,” he said. “I have ridden on the bikeway once and I’m not going to do it again until it’s resurfaced. it was actively painful.”

Greg Raisman, traffic safety specialist for the Portland Bureau of Transportation, wrote in an email that Michigan functions “more as a feeder route” in the bike network than as a collector, and that bike traffic is likely to grow on Michigan over time as it has on other neighborhood greenways.

“When Ankeny and Lincoln/Harrison were first implemented, it took some time for people to learn about the improvements and adjust their routes to take advantage of them,” he wrote. “Today, these routes carry more than 200 bicycle trips an hour in peak. … Also, if we are successful with securing additional transportation revenue, there are some things we could do to further improve Michigan that would likely attract riders.”

Update 2:52 pm: The charts in an earlier version of this post expressed average traffic counts for one direction only. The new charts express average counts in both directions for each location, which we feel is more intuitive. The trends are unchanged.