When it comes to American cities trying innovative things in the transportation realm, there’s an unfortunate tradition of mainstream media and the usual skeptics going into full, “sky is falling!” mode. Before the first major bike share system launched and before congestion pricing was implemented in New York City, the outrage machine kicked into high gear — only to fall silent when the things ended up working out as advertised (if not better).

Portland’s ‘zero emissions delivery zone’ effort was no different. When news of the transportation’s bureau’s project came to light, local media did their thing. It got so bad I had to publish a story just to try and set the record straight. And now that the six-month pilot is over, a report issued by the City of Portland last week says it was a success.

Portland experimented with zero emission delivery zones because our city has adopted climate and freight plans that specifically prioritize making trucking less toxic to the environment. Around 40% of Multnomah County’s carbon emissions come from the transportation sector and the Portland area is in the top one percent of the areas with the highest diesel emissions in the U.S. Beyond the health of our lungs and planet, the current delivery truck fleet is large and operators too often take advantage of lax enforcement. This leads to congestion and safety hazards when drivers double park, circle around to find parking, block public spaces during deliveries, and so on.

From a bike safety perspective, the use of big trucks in the downtown core has been a major concern for many years and we’ve had too many people killed in collisions with truck operators.

To address these issues, in 2023 the Portland Bureau of Transportation won a $2 million grant from the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Strengthening Mobility and Revolutionizing Transportation (SMART) program. The idea was to cut emissions from central city truck deliveries and encourage different types of vehicles to make them. PBOT chose to focus on curb zone and parking regulations to achieve their goals.

“Cities are the centerpiece of the economy and we control valuable assets, like the curb zone,” stated PBOT Director Millicent Williams in an introduction to a report on the six-month pilot project released last week.

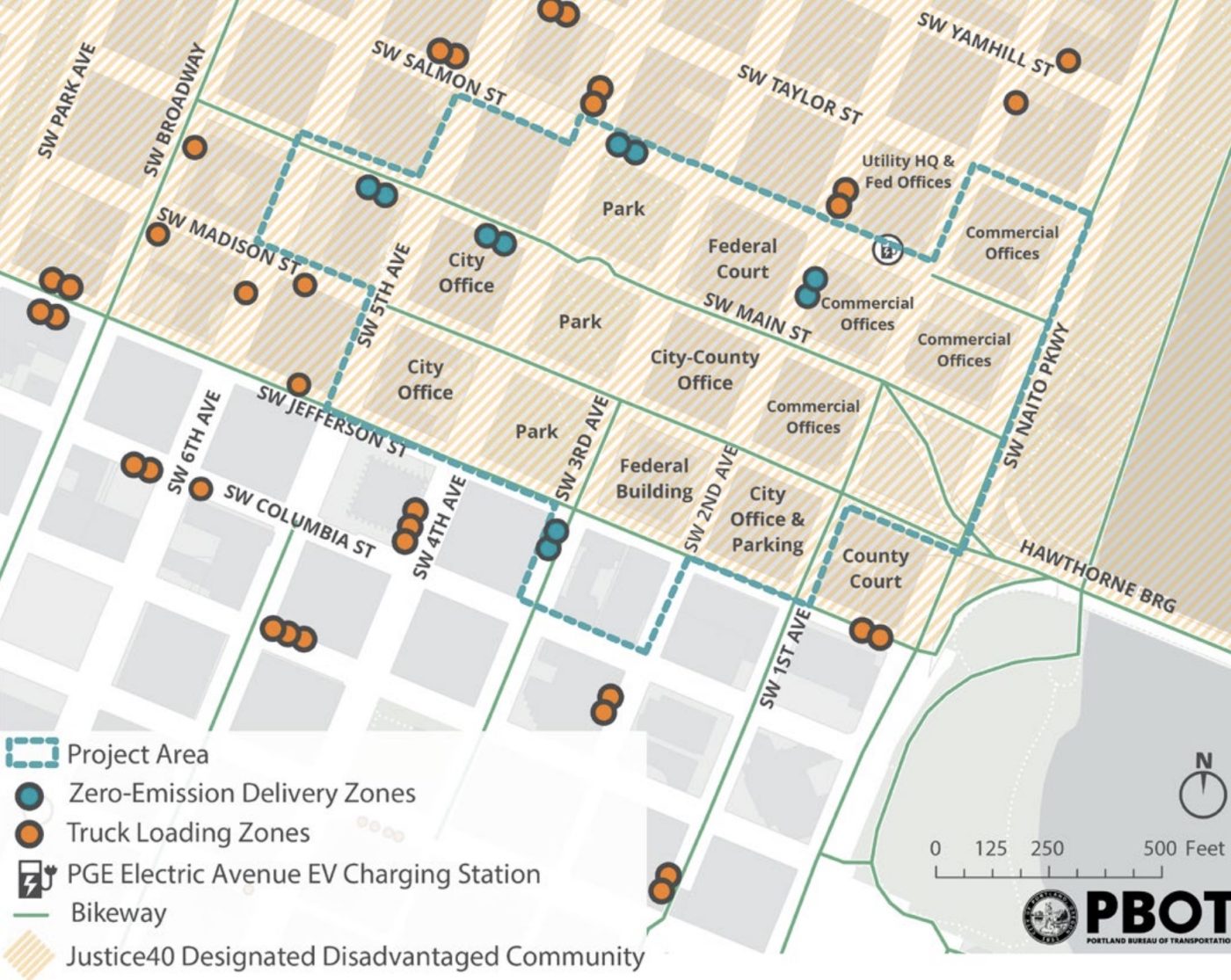

PBOT’s pilot project consisted of a 16-block area of downtown (roughly SW Naito to 6th and Salmon to Jefferson) where only zero-emission delivery vehicles were allowed to use 10 specific loading zones. Vehicles with internal combustion engines could still use metered parking spaces, internal loading bays, or they could do their loading outside the zone. To help companies comply with the new regulations and to assist their parking enforcement teams, PBOT created a free, digital parking permit.

PBOT staff also worked directly with delivery companies to help them find solutions for their businesses that would comply with the experiment. They helped companies source zero-emission vehicles, tested the use of microhubs where electric vehicles could operate efficiently, and encouraged the use of electric cargo trikes for last-mile deliveries. In the report, PBOT says they “promoted cyclelogistics,” and most of that effort focused on B-line Urban Delivery, a local company that made 45,000 deliveries to over 200 customers by pedal (and battery) powered electric cargo trikes last year.

PBOT connected B-line to new potential customers, worked with traffic data firm INRIX to map e-cargo trike routes and usage, and explored policies and programs that could increase e-cargo trike deliveries in the future. This is very promising collaboration! To give you a sense on where PBOT’s head is regarding e-cargo trike deliveries, read this excerpt from the report:

“In urban areas, cargo bikes can be an effective replacement for last-mile delivery vehicles with internal combustion engines. Among other benefits, cargo delivery bikes (including e-cargo tricycles) reduce harmful pollution, take up less curb space, can avoid congestion by using bicycle infrastructure and occupying less roadway space, enable parking closer to the delivery destination, and pose less of a danger to other road users. They also cost much less to purchase and maintain than a delivery truck, providing cost savings. While they aren’t suitable for all environments or delivery types and then may carry fewer goods, a UK study estimated 10–30% of trips by delivery and service companies could potentially be replaced with e-cargo bikes.”

One of the most promising steps PBOT could take to encourage more delivery trikes is to establish more microhubs near major destinations. “Building cyclelogistics microhubs in central locations could enable bicycle delivery companies to operate efficiently and reliably,” PBOT writes in the report. And if you think this is all talk and no action, consider the steps already taken to establish one such delivery hub at the future James Beard Public Market.

B-line CEO and Founder Franklin Jones told BikePortland this morning he was impressed with how PBOT approached this work. “The pilot showed PBOT has a serious interest in tackling real challenges associated with urban logistics,” and it, “underscored that innovation and collaboration between the public and private sector is alive and well,” he said.

So, how do we know it worked? Here are a few tangible results touted by PBOT in their report:

- Six new companies contracted with B-line for delivery services.

- Over 65 zero-emission vehicle digital permits were issued.

- Delivery company DHL bought three electric vehicles for deliveries in Portland and installed new chargers at their local facility.

- Amazon rerouted their zero-emission vehicles into the pilot area.

- The first FedEx-branded zero-emission vehicles in Portland were spotted in the project area in March 2025.

- HYPHN, a Portland-based moving company, purchased their first zero-emission vehicle as a result of the pilot.

- The City of Portland Printing & Distribution department led by example and purchased an electric van for local deliveries, a move estimated to avoid nearly 90 metric tons of GHG emissions — the equivalent to carbon sequestered by 90 acres of forests in one year — over its lifetime.

From here, PBOT wants to push further. Their next steps wish-list includes: expand the zero-emission zones, consider new enforcement strategies, develop a pilot for on-street microhubs, and update city policy to support e-cargo trikes — which they see as including quadricycles and electric-assist trailers.

Portland has a commitment to slash carbon emissions by 50% or more by 2030 and to be net zero by 2050. Despite the fears this new approach to an old problem stoked in some circles, it seems like a great success for our city and the planet on several fronts. Or, as the report states: “For the City, this pilot represents another step toward encouraging a future of decarbonized transportation.”