The bad news about the latest city bike counts is that the number of people cycling in Portland didn’t make a big jump in 2024. The good news is that it didn’t go down. Not only that, but we are in a phase the City of Portland has officially dubbed “a new beginning” as ridership numbers continue to rebound after pandemic doldrums.

According the annual bike count report from the Portland Bureau of Transportation, cycling “remained steady” in 2024. Portland has done annual, manual bike counts for over 30 years, longer than any other American city. Between June and September of last year, 170 volunteers equipped with clipboards and pens fanned out to 318 locations across the city. They tallied every person who came by that was on a bicycle or some sort of micromobility vehicle (like a scooter, one-wheel, and so on).

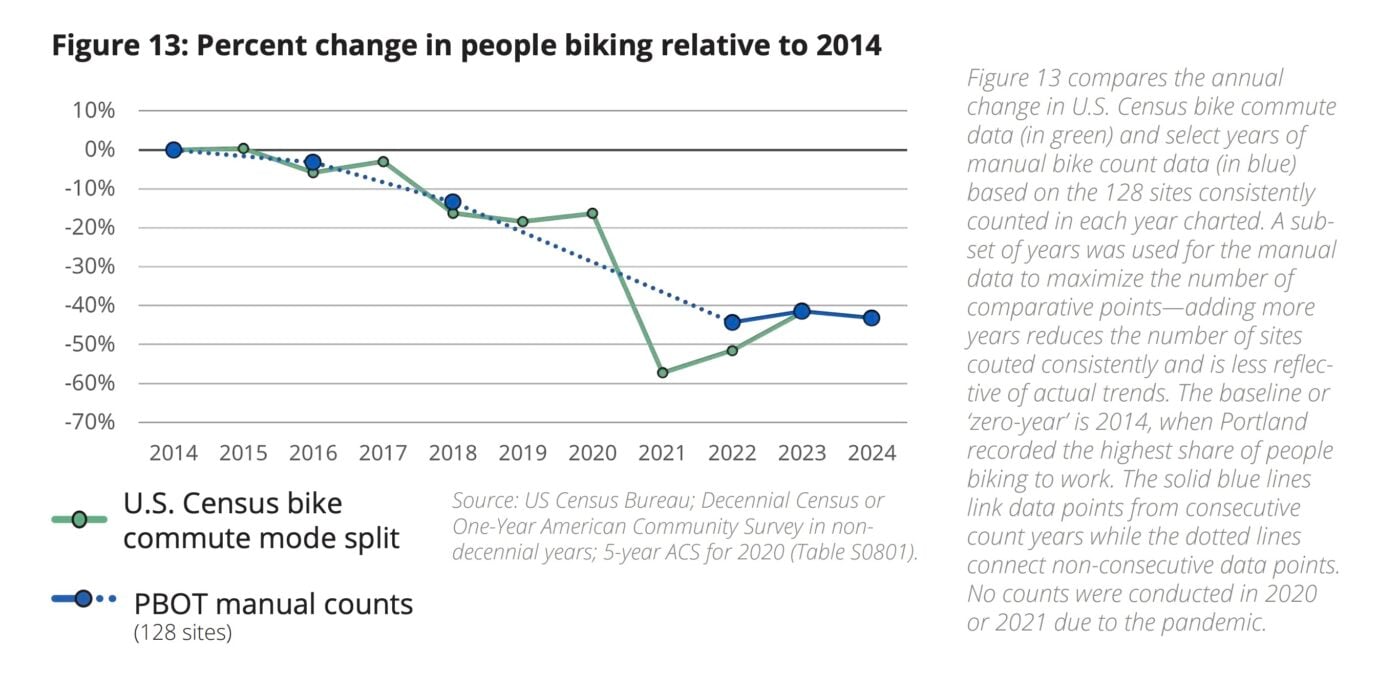

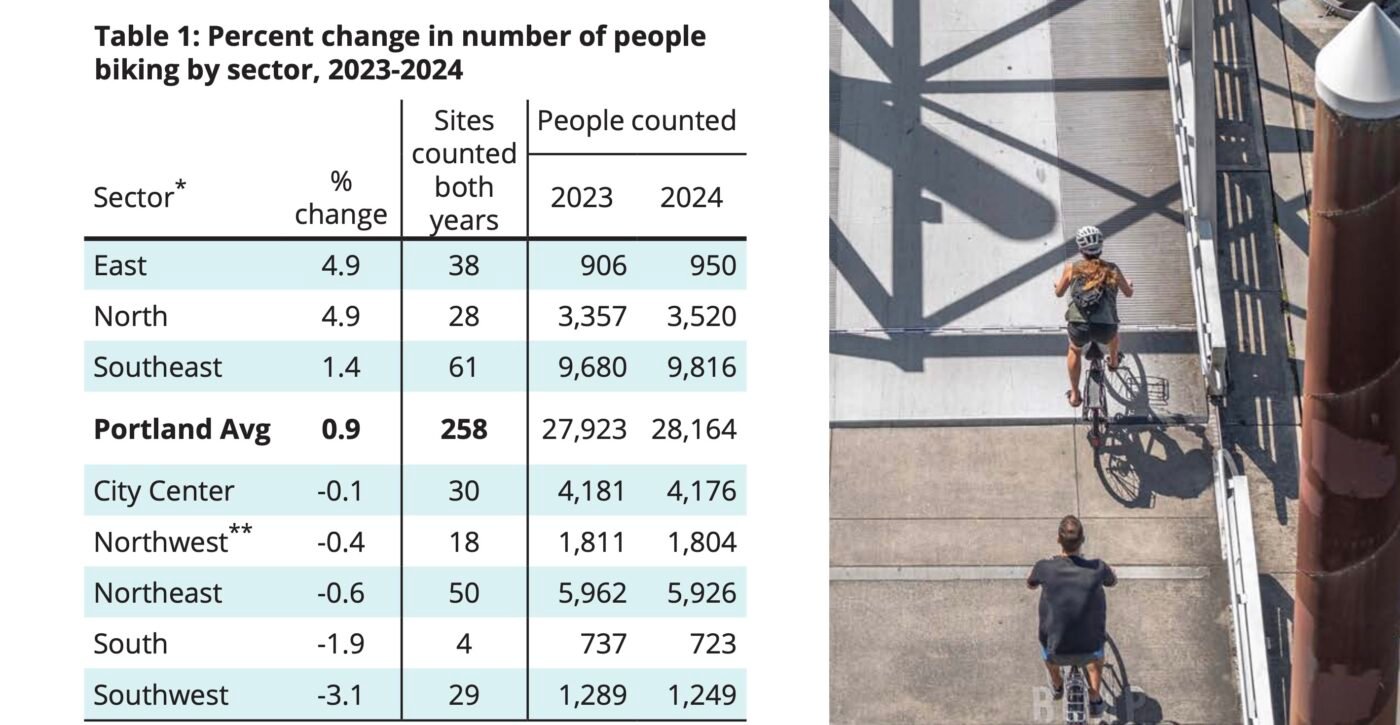

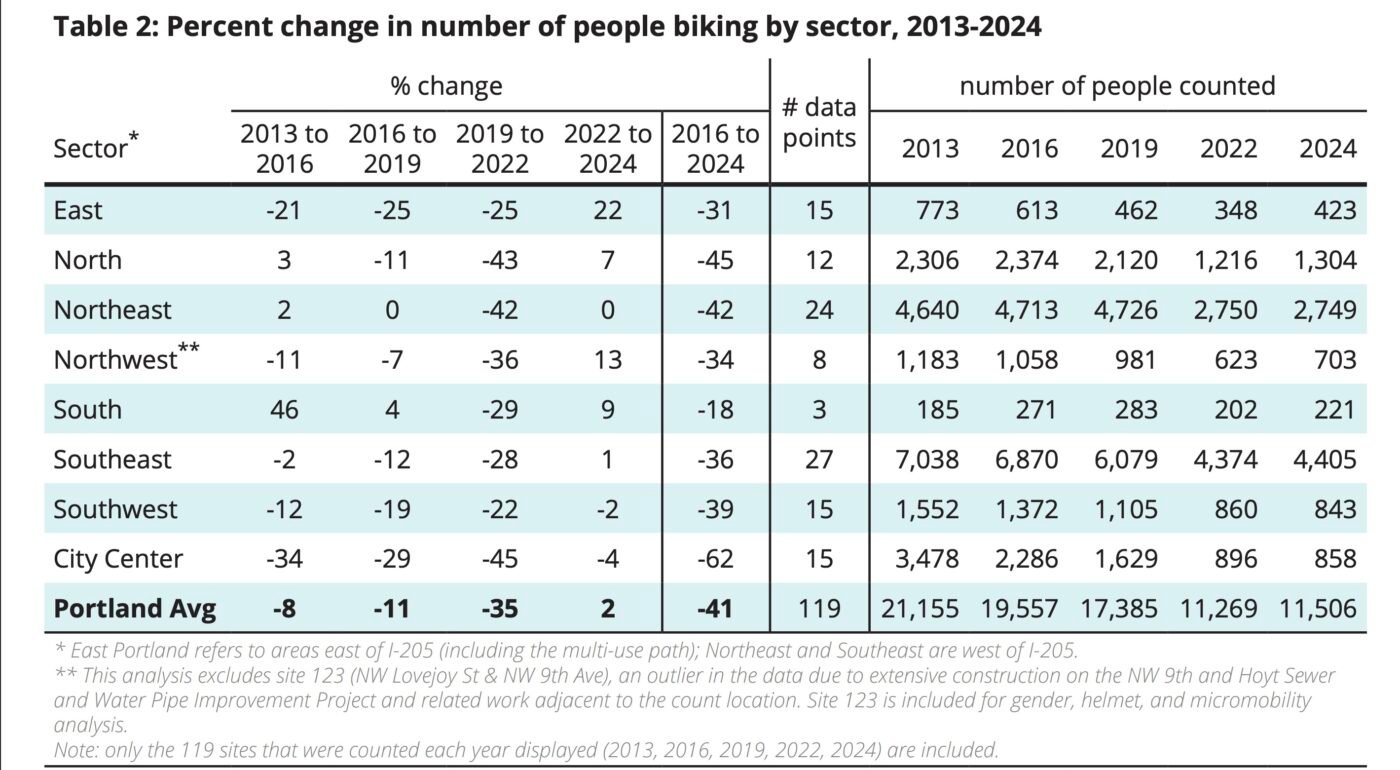

Across 258 locations counted in both 2023 and 2024, there was an average, citywide increase in riders of just 0.9% over last year — 27,923 cyclists and 28,164 cyclists respectively. For perspective, across 119 sites that were counted in both 2016 and 2024, the number of people biking is down by about 40%.

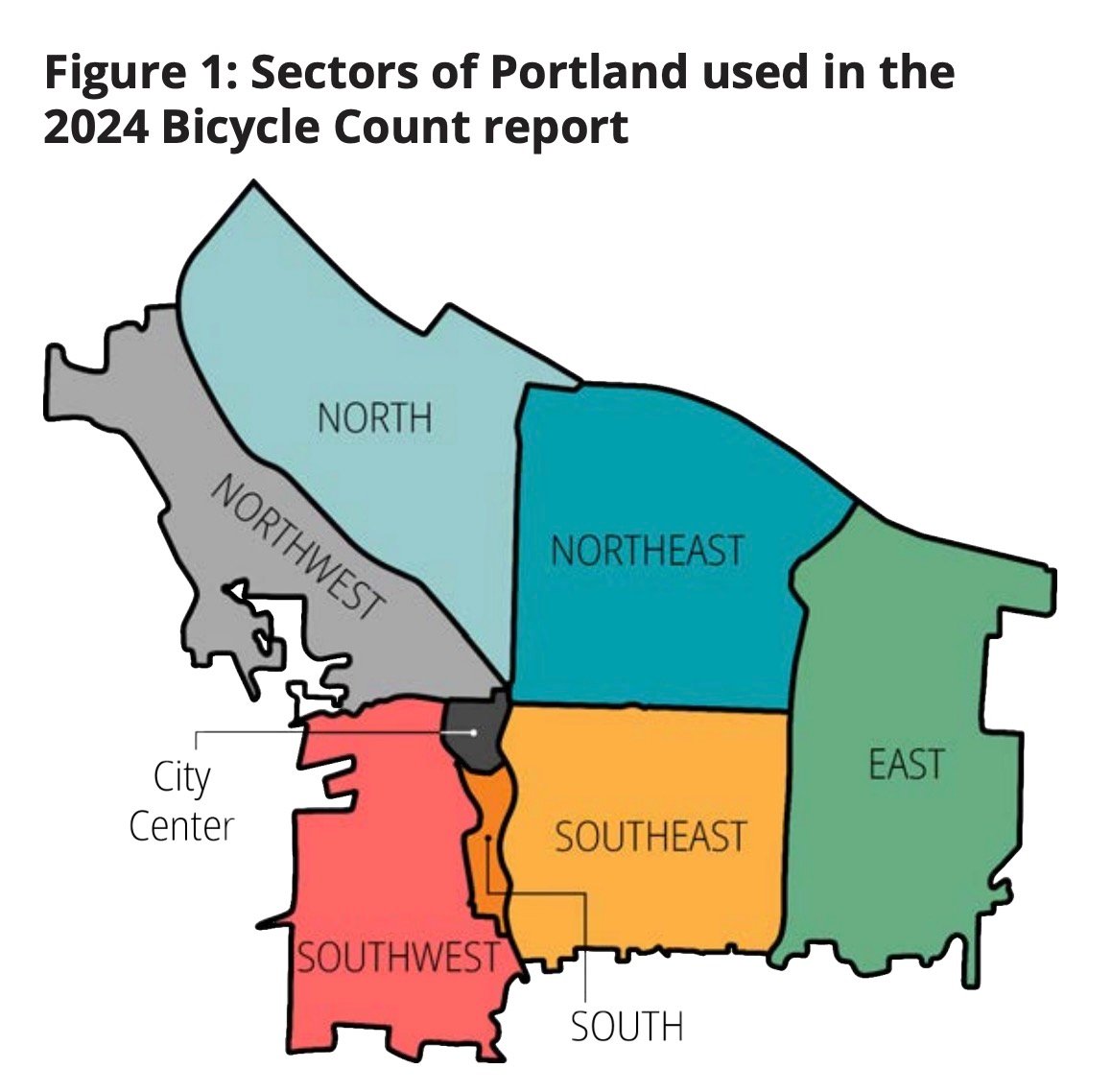

The city split the count locations into eight distinct sectors (see map below). Of those districts, three tallied an increase and five had a decrease. East and North saw the biggest jump in ridership (relative to 2023) at 4.9%. Southwest meanwhile, saw 3.1% fewer riders than last year.

After nearly two decades of steady and strong growth in cycling between the early 1990s and 2015, Portland’s bike use has stymied in the past decade. To help describe what’s going on, PBOT has released a new narrative explanation. Here’s an excerpt from the count report:

Through our analysis of the data, the story of bicycling in Portland over the past 20 years can be told in four parts.

- The surge (pre-2016): Bicycle use steadily increased from the early 1990s. Portland set a national record for bicycle modeshare in a large city (population greater than 300,000) with 7.2% of people biking to work in 2014. The number of people bicycle commuting peaked in 2015 at 23,432 even though the mode split slipped slightly to 7% due to population growth.

- The ebb (2016–2019): Commuting by bike began a slow decline in both percent of trips and number of commuters after 2015 even as the city’s population grew.

- The pandemic (2020–2022): Biking, like all forms of transportation, decreased dramatically during the pandemic.

- A new beginning (2023–2024): Similar to other cities, the number of people biking has ticked up from pandemic-era lows and is holding steady as Portland continues its post-pandemic recovery.

The methodology of this count is open to critique, but PBOT would say the value is in its consistency over time. Similar to the quibbles cycling advocates have had with the U.S. Census bike commute mode share number, those concerns are balanced against the fact that the data offers a consistent view over a long time period.

On that note, PBOT gleans their numbers by counting each of the 318 different locations once between June 4th and September 26th (prime cycling season in Portland). The counts are done mid-week and volunteers count for a two-hour period during what PBOT says is the peak cycling hours of 4:00 to 6:00 pm or 7:00 to 9:00 am. (Given the vast increase in people working-from-home since the pandemic in 2020, you can see how this type of count would be impacted.)

PBOT then takes those two-hour counts and (“using a standard traffic engineering rubric”) makes an assumption that they account for about 20% of all daily bicycle trips at each location. That estimate is then considered to represent a full weekday count for each site.

In 2023, the first time PBOT volunteers made a separate tally for electric bikes, they counted 17% of people using bikes with motors. In 2024 that number dwindled to 9%. However, PBOT says the e-bike number is likely a significant undercount, “because newer e-bikes are increasingly designed with features that make them look similar to non-electric models.”

When you add e-bikes to other types of micromobility vehicles like e-scooters, one-wheels, and electric skateboards, that category made up 14% of all trips counted in 2024.

PBOT’s count report also includes insights on the shared bike and scooter programs known as Biketown, which currently consists of 2,350 e-bikes and 3,500 e-scooters citywide. Ridership on both modes has rebounded well since the pandemic in 2020, but PBOT reports a trouble decline in Biketown ridership, which saw a 15% decrease in 2023.

PBOT says the decline in Biketown e-bike ridership is likely due to a number of factors (riders have complained about poorly maintained bikes, and the system service area has expanded without a commensurate increase in bikes), but that the bulk of the decrease is due to changes in their Biketown for All program for low-income riders. As I reported in May, PBOT scaled back the program to cut costs. The city adjusted the program’s eligibility requirements and switched from providing unlimited, free 60-minute trips to providing a $10 credit per month with rides billed at five cents per minute. “The change was made in response to rising costs that threatened the financial stability of the program, which had grown from 169 users in 2020 to 4,270 when the change was implemented,” PBOT writes in the report. Likely as a result of those changes, PBOT has seen Biketown for All use decrease by 21% in 2024.

Despite the relatively flat ridership numbers, PBOT says their are reasons for optimism going forward. In the conclusion of the report, they say the city’s bike network is “more robust and far reaching than it was a decade ago when Portland was setting national records for biking” (but is that enough to counterbalance the rise in drivers and associated erosion of street safety?). PBOT also points to more automated enforcement, major new bike lane maintenance investments, and a new form of city leadership that, “promises fresh ideas and more collaborative city operations,” as reasons for a brighter bicycling future.

The report ends with a bit of editorializing and a call to action:

“Portland can be a world-class bicycle city, but only if we’re committed to making it that way. Prevailing U.S. policy, funding mechanisms, and culture favors less travel choice, more car dependence, rising vehicle traffic, and more traffic fatalities. These outcomes are not flukes; they’re consequences. But Portland is making different choices. We can change for the better. And change is necessary for a brighter, more bikeable future.”

Read the full report here.