Oregon has had a $15 tax on all new bike purchases for almost six years now. It passed as part of the House Bill 2017 transportation funding package and went into effect January 1st, 2018. At a meeting on Tuesday that included state lawmakers, Oregon Department of Transportation staff, and leaders from various interest groups, there was an that made it seem like a change in the tax is imminent.

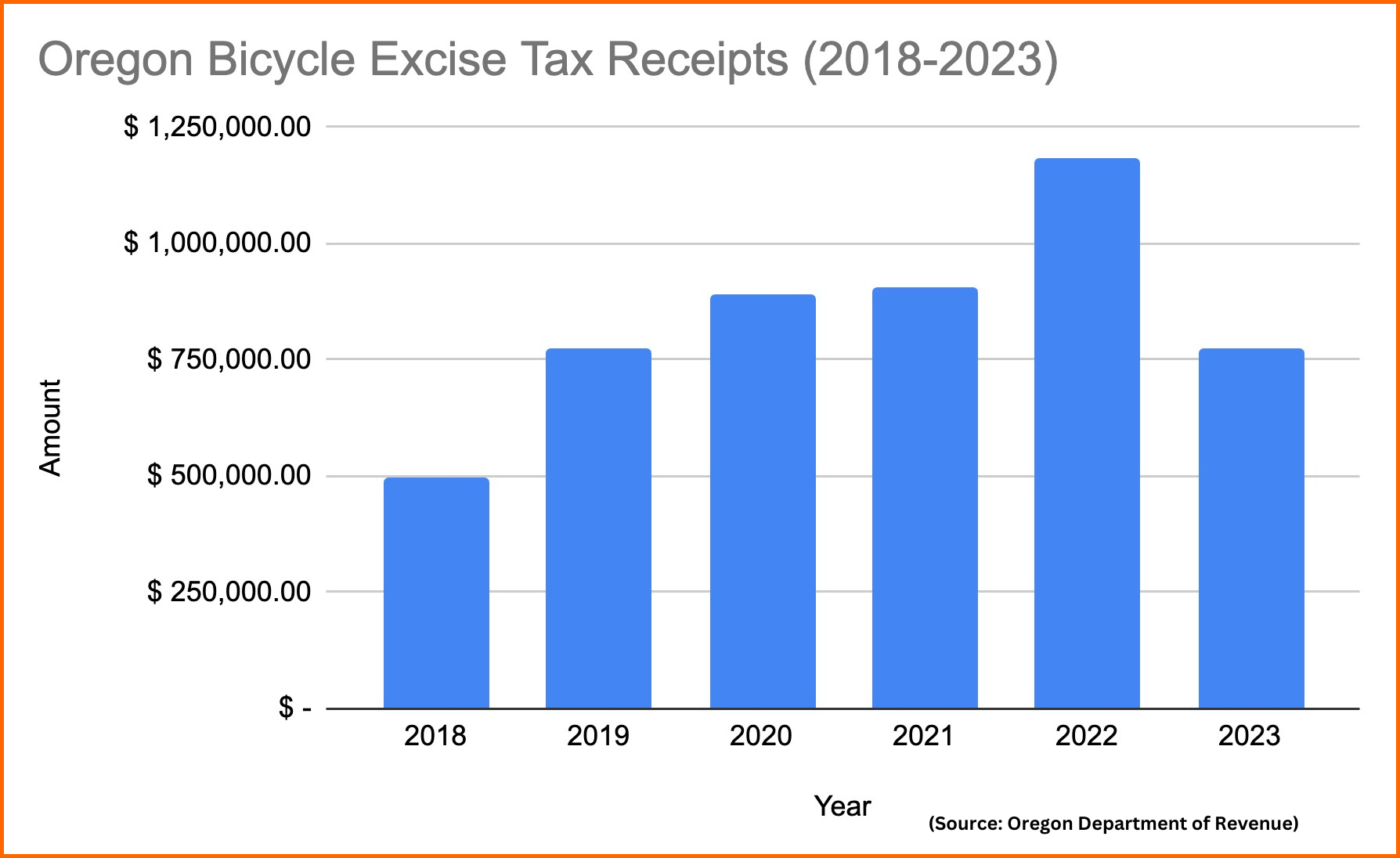

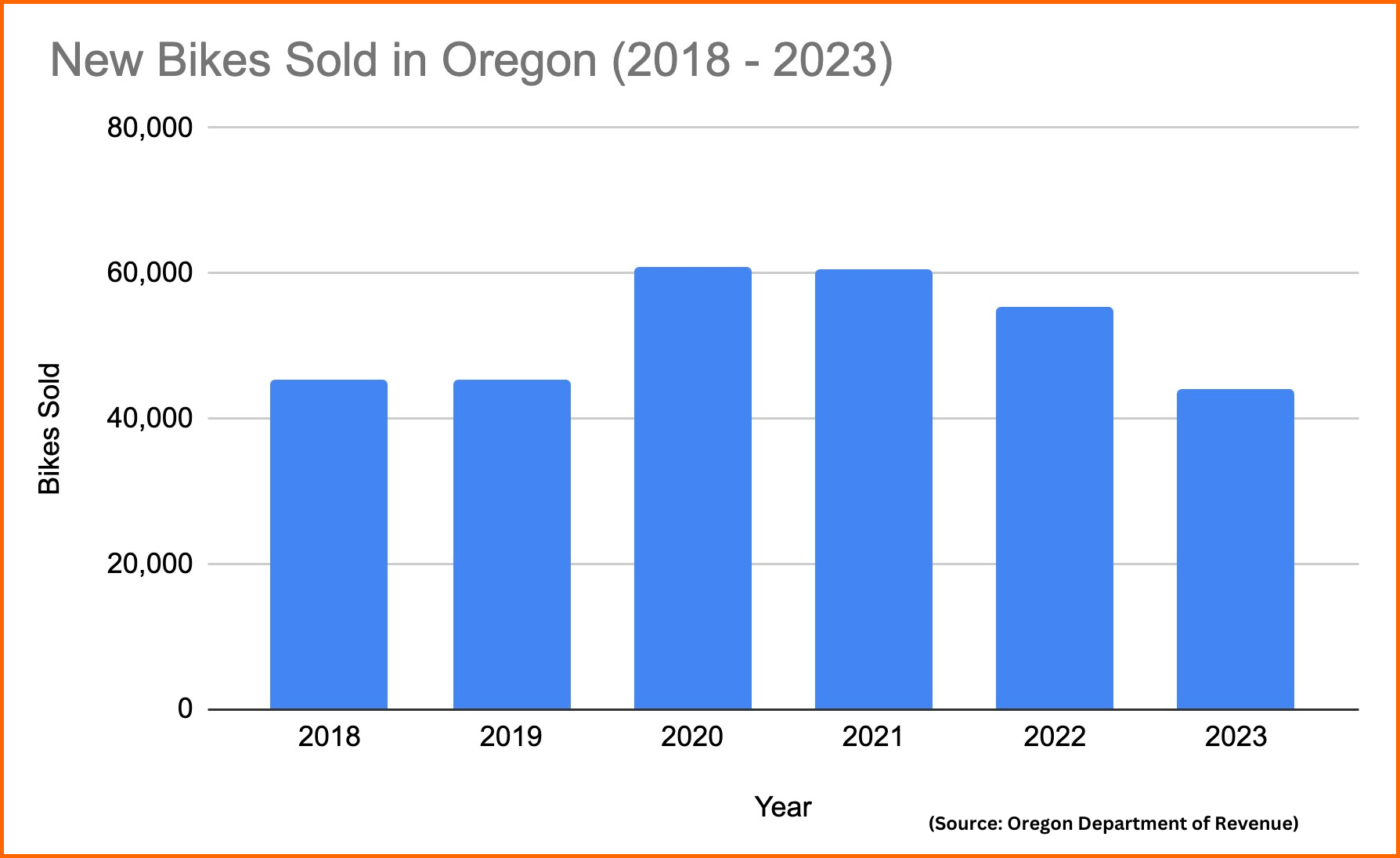

The Bicycle Excise Tax was a political compromise stuffed into HB 2017 in order to lessen the blow of other taxes targeted toward car owners, buyers, and sellers. It was not strongly opposed by advocacy group The Street Trust, who wanted to pass a bill in order to garner set-aside funding for Safe Routes to School and it hoped it would give cycling and active transportation advocates an answer to the perennial bad faith argument that, “bikes don’t pay their fare share.” The tax raises an average of about $833,000 per year on sales of about 51,000 new bikes purchased in Oregon (or by Oregonians from online sellers). The $5 million raised so far has been put into a grant program that funds off-highway paths.

The tax was discussed at the final meeting of a workgroup convened by the Oregon Legislature’s Joint Committee on Transportation that is setting the groundwork for a new transportation spending package that will be proposed in the coming session. In that meeting, Oregon Department of Revenue Policy Coordinator Xann Culver shared a presentation about the tax to inform the lawmakers and advocates in the workgroup.

In response to Culver’s presentation, Duke Shepard, a workgroup member and senior policy director for Oregon Business & Industry (a nonprofit advocacy group based in Salem) said, “It struck me as puzzling that it’s a $15 fee regardless of the price of the bike.” It’s a good point, given that the tax begins at bikes costing as little as $200. That triggered a conversation about the tax.

House Representative Susan McLain (D-Hillsboro) was one of the architects of HB 2017 and is now a co-chair of the Joint Committee on Transportation. She responded to Shepard by saying that, essentially, there wasn’t enough time to analyze the fairness of the bike tax and $15 was just the number they came up with. “We hadn’t had a bike tax before,” McLain said. “And so the idea of even having a bike tax was a big lift.” McLain added that they wanted a number high enough to make the tax worth it, but not high enough so that it discourages bike use.

But what we’ve been left with is a regressive tax that is much higher than a similar tax on new cars that was also passed in HB 2017.

State of Oregon Senior Economic Mazen Malik was also in the meeting. He called the $15 the “least acceptable compromise at the time” and that a 7.5% tax on the retail price of new bikes was also considered. “The idea was primarily to start this process [of a bike tax] and see if it sticks, and then if the progressivity element needs to be injected into this subsequent legislatures would look into that.”

For Oregonians who purchase a $200 bicycle, which is about the cheapest you’ll find even at a big box retailer, the $15 bike tax equates to 7.5% of the total purchase price. By comparison, Oregon’s “vehicle privilege tax” (also passed in 2017) that’s charged to car dealerships, is just .05% of the retail price of a new car. For a $20,000 entry-level car, sellers pay tax of just $100. If they paid at a rate similar to the bike tax they’d pay $1,500.

Put another way, in the current system, the tax rate on an entry-level bicycle is 15 times higher than that of an entry-level new car.

That point was made by Oregon Trails Coalition Executive Director Steph Noll at Tuesday’s meeting. “That $15 tax is such a higher percentage that what our vehicle privilege tax is,” she said. “So if we’re looking at making it more progressive, even if we were to double the current bike tax, it really doesn’t do much towards filling the revenue gaps that we are looking at.”

House Rep (and now Senator-elect) Khan Pham, who was facilitating the meeting, echoed Noll’s sentiment. She said that even if a bike tax raised $1 million per year it would be an almost unrecognizable amount amid the multiple billions Oregon needs to raise. Changing the bike tax is, “Something that we definitely do need to address in the coming up, the upcoming session,” Rep. Pham said. “Because you’re right; those are very different price points, and we want to make sure we’re being equitable.”