Some people, upon hearing cycling and transportation activists talk about new road designs or different infrastructure funding priorities, respond with statements like, “but not everyone can bike” or “some of us need our cars.” What’s lost in these debates is that even a relatively small shift in how we get around, Oregonians — and the state of Oregon itself — could see major positive impacts.

As part of their preparation to build a 2025 transportation funding package, the Oregon Legislature is hosting meetings to educate lawmakers and hear input from experts (I mentioned these workgroups in my previous post about the budget). In a November 20th meeting of one of these workgroups, Miguel Moravec from the Rocky Mountain Institute shared a presentation about how Oregon would benefit from a shift in mode choice.

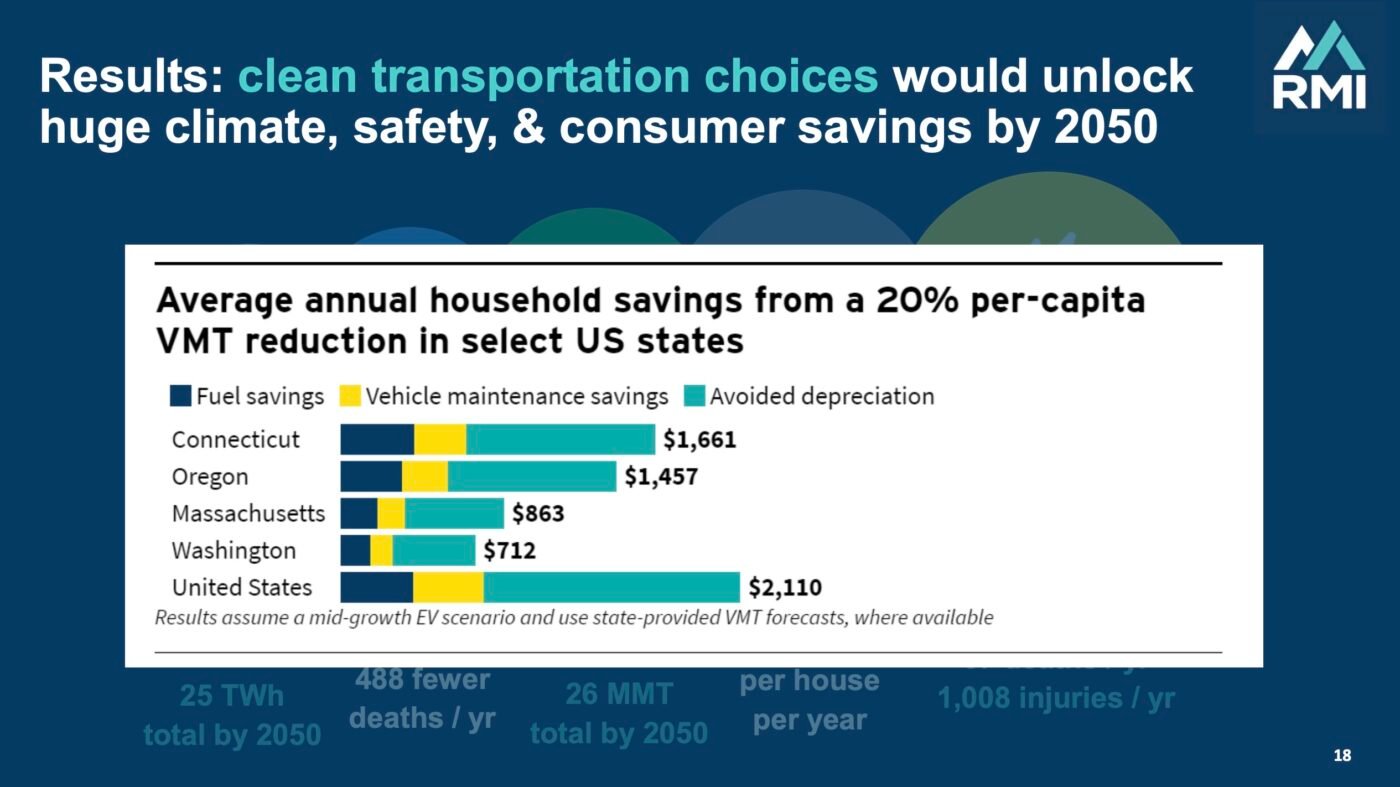

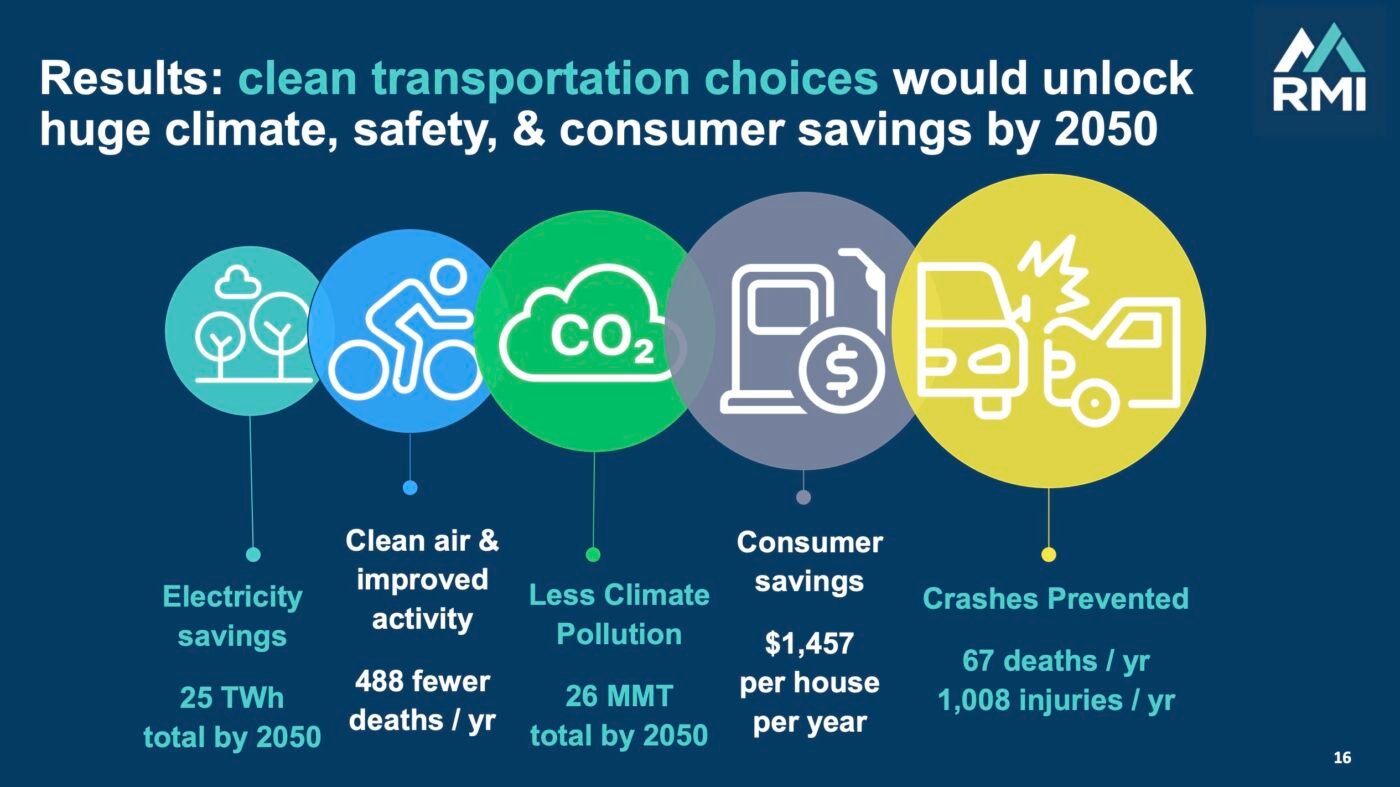

RMI is a nonprofit think tank that started during the oil crisis of the 1970s and now provides research and analysis “to advance the clean energy transition.” You might have heard about their widely-used induced demand calculator tool, which is used by The Street Trust in their candidate training program. Moravec brought a different tool to the legislative working group: something RMI calls their “smarter modes calculator.” Using that calculator across a 2024-2050 timeframe, Moravec based his presentation around what would happen if Oregon was able to shift just 20% of its current driving miles to other modes like walking, cycling, or transit.

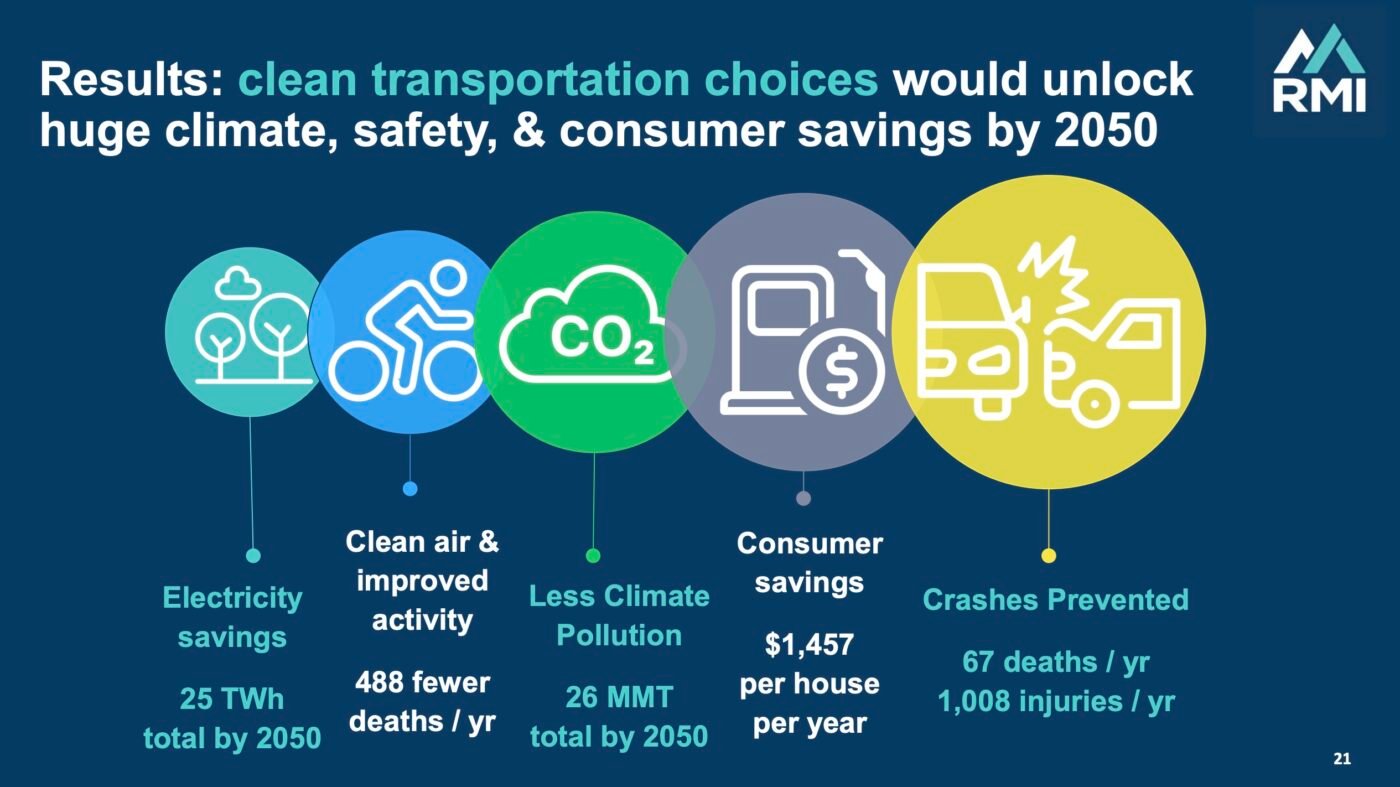

According to Moravec, if Oregon residents shifted just one out of every five auto trips to a non-driving mode, every household would save $1,457. “This is a literal stimulus check-sized boost,” Moravec said. (Or about $500 larger than the size of an average “Oregon kicker” rebate.) RMI’s household savings number is based on the fact that the average cost to own and maintain a car in the U.S. is about $12,000 per year and the average Oregon household owns two cars.

Other benefits of a 20% vehicle miles traveled (VMT) reduction would include: 488 fewer deaths per year due to improved air quality and more physical activity, and a reduction in crashes that would save 67 lives and prevent over 1,000 injuries per year. If that’s not enough to sweeten the deal, a 20% shift would prevent 25 metric tons of CO2 from being released into the atmosphere. There’s a cost to road crashes too, and RMI’s calculator reveals that Oregon would save $35 billion just by putting down their car keys and lowering road exposure time.

There would be other livability and urban planning benefits as well. Moravec used a case study of Arlington, Virginia, to show how when city planners made non-driving modes more attractive, they also boosted the local economy. “Clean transportation choices in Oregon can stimulate Main Street economic activity, and it’s a virtuous cycle because as residents’ need to drive decreased, the area became more desirable to live.” More human-centric places create a stronger tax base for local governments, Moravec shared, a benefit that is amplified when fewer car trips lead to savings on road maintenance costs.

To unlock all these benefits, Moravec said lawmakers cannot just hope people change behaviors on their own. The legislature must support and implement laws and programs that entice fewer car trips. What type of policies do this? His presentation pointed to congestion pricing in New York City, as well as a state payroll tax and casino tax. In New Jersey, lawmakers have passed a tax on corporate incomes to fund transit. Colorado and Minnesota have a fee on home deliveries from the likes of Amazon to fund transportation options, and Minnesota is expected to raise $700 million a year from a combination of regional sales taxes.

Keep in mind this presentation was being heard by a very influential and powerful group of lawmakers, advocacy leaders, and ODOT staff that included: Co-chairs of the Oregon Legislature Joint Committee on Transportation Senator Chris Gorsek and Rep. Susan McLain, Oregon Transportation Commission Chair Julie Brown, and many others.

Rep. McLain expressed interest in the home delivery fee and Rep. Kevin Mannix wanted to know more about the funding package passed in Minnesota.

This was just one of many presentations that has been shared with lawmakers in recent weeks and months. I’ve been impressed with the amount of information and feedback that’s being processed during these workgroup meetings and can’t wait to see what type of proposals end up on the table once the legislative session begins next month.