With just 18 days left to submit an official comment into the Interstate Bridge Replacement Program (IBRP) Supplemental Draft Environmental Impact Statement (SDEIS), some advocates say they can’t properly assess the project because its leaders are using bad data to analyze the design proposal. Allegations are swirling that transportation department staff and project consultants have “cooked the books” by intentionally manipulating traffic data to justify investing an estimated $7.5 billion on a wider freeway and seven new interchanges across a five-mile stretch of I-5 between Portland and Vancouver.

The IBRP is successor to the Columbia River Crossing (CRC), a project that many thought died in 2014. 10 years later, the megaproject is alive and well with a new name and a new legion of consultants and transportation department staff from Oregon and Washington committed to getting it built. The project has secured $4 billion in federal and state commitments, and while it faces fewer controversies and legal headwinds (so far) than the I-5 Rose Quarter project a few miles south, the IBRP still faces serious questions.

One big problem is that critics and project leaders don’t agree on the same set of basic facts. The ability of people to “meaningfully evaluate” the impacts of a proposed project form the bedrock of the federal National Environmental Policy Act the IBRP is obligated to follow. But experts and outsiders say IBRP staff make it impossible to evaluate the project because the numbers, models, and data being used by project staff are incomplete and/or wrong.

“This is all fantasy numbers,” said Chris Smith, a co-founder of No More Freeways, one of 36 groups in the Just Crossing Alliance coalition that wants to “right size” the project. “How can we meaningfully evaluate the impacts, which is what the EIS [Environmental Impact Statement] is supposed to be about, when it’s all make believe?”

I spoke to Smith a week after Just Crossing Alliance held a press conference to share a 29-page report by an outside consultant that looked at the IBRP’s traffic modeling. Models are used to estimate the future amount of cars, trucks, bikes, and transit users on a given piece of infrastructure. A major concern of advocates tracking the IBRP is that the model that underpins all assumptions about the current proposal is outdated. They say not only is the model bad, but that IBRP officials are manipulating numbers that come from it to suit narratives required to build a more expensive — and expansive — project than needed.

“Garbage in, garbage out.”

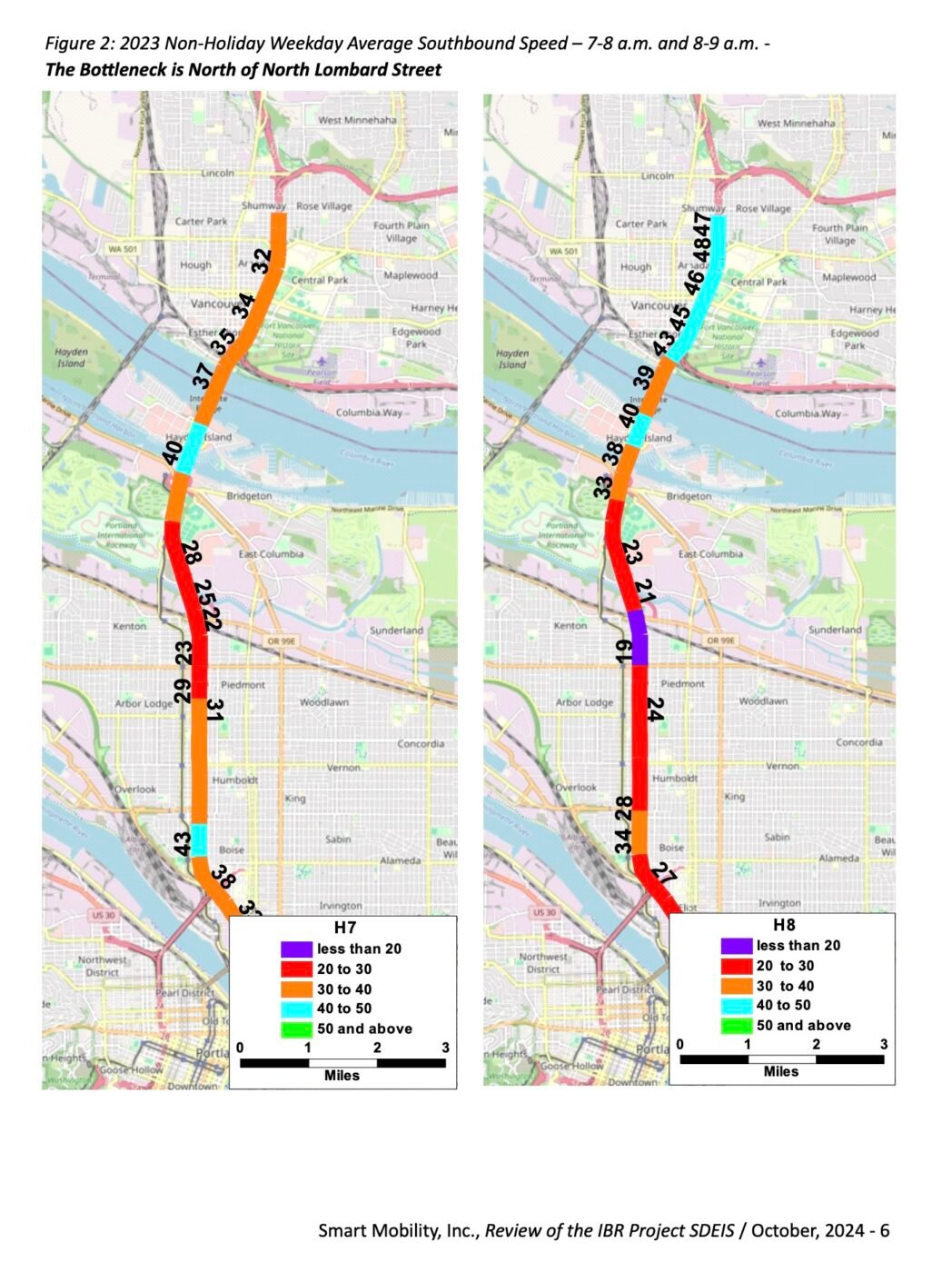

The report, Review of the IBR Project SDEIS, was published by Smart Mobility Inc. President Norman Marshall, an expert with nearly four decades experience in transportation demand modeling who’s completed projects with city governments across the country. Marshall says IBRP is solving for the wrong thing. His examination of traffic data shows the Interstate Bridge is not the bottleneck and that “widening the bridge would do nothing to improve I-5 congestion and could make it worse.”

By analyzing traffic flow and speed patterns, Marshall found congestion in the bridge area actually originates further south at N Lombard during the morning peak and at N Victory Blvd northbound in the afternoon peak. And he says new driving lanes and larger interchanges proposed in the IBRP will encourage more traffic because of induced demand — a proven phenomenon that the SDEIS “almost completely sidesteps” reports a story by The Urbanist this week.

The IBRP SDEIS says the bottleneck originates at the bridge; but Marshall proves in his report that that statement, “is simply wrong.” “The DSEIS fundamentally misrepresents existing northbound [and southbound] traffic conditions in the I-5 corridor,” he writes in the report. “And in doing so, creates an erroneous ‘need’ for the project.”

(Above: Pages from Marshall’s report.)

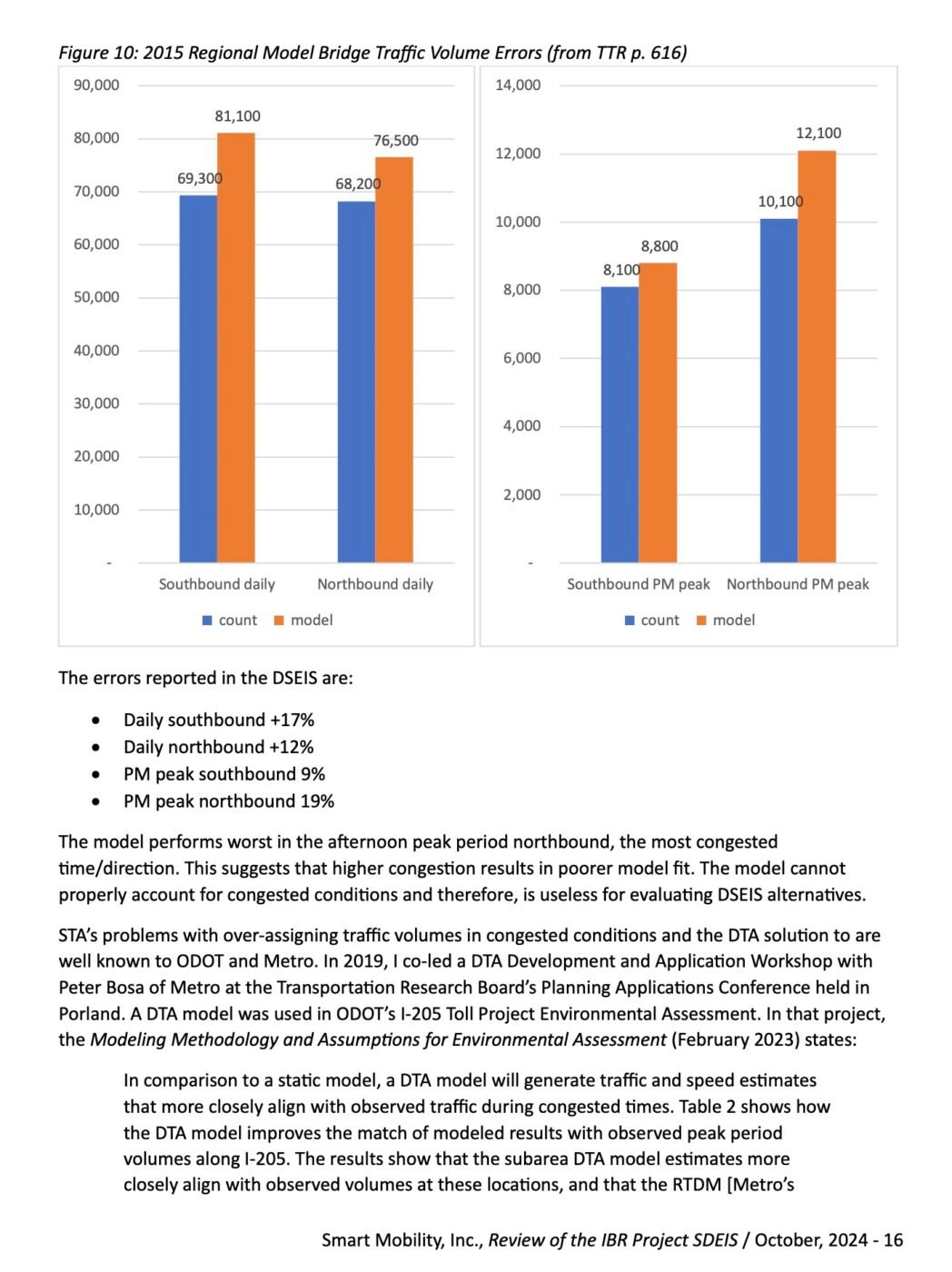

Marshall also blames Metro’s regional travel demand model (which the SDEIS is based on) for using a process that is outdated (it was created in the 1960s) and only considers traffic in a specific area (known as the “static traffic assignment” or STA process), as if traffic volumes within project boundaries are not influenced by traffic volumes outside it. That means known bottlenecks just south of the IBRP project area don’t figure into the analysis of traffic flow within the project area. That’s, “a plainly unrealistic assumption,” Marshall writes in the report.

And here’s why:

“Treating every roadway segment as independent causes the regional model to exaggerate the benefits of widening individual segments because it assumes that traffic throughput can grow on road segments even where traffic growth is prevented by upstream and downstream bottlenecks.”

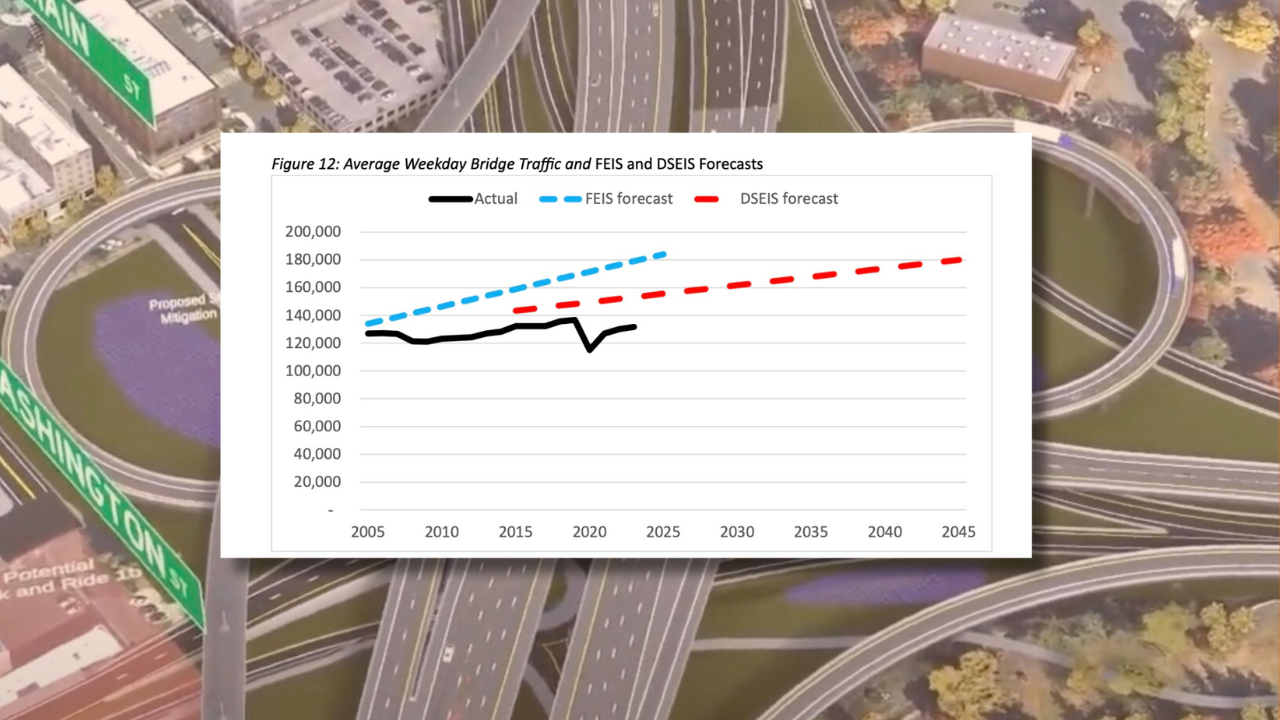

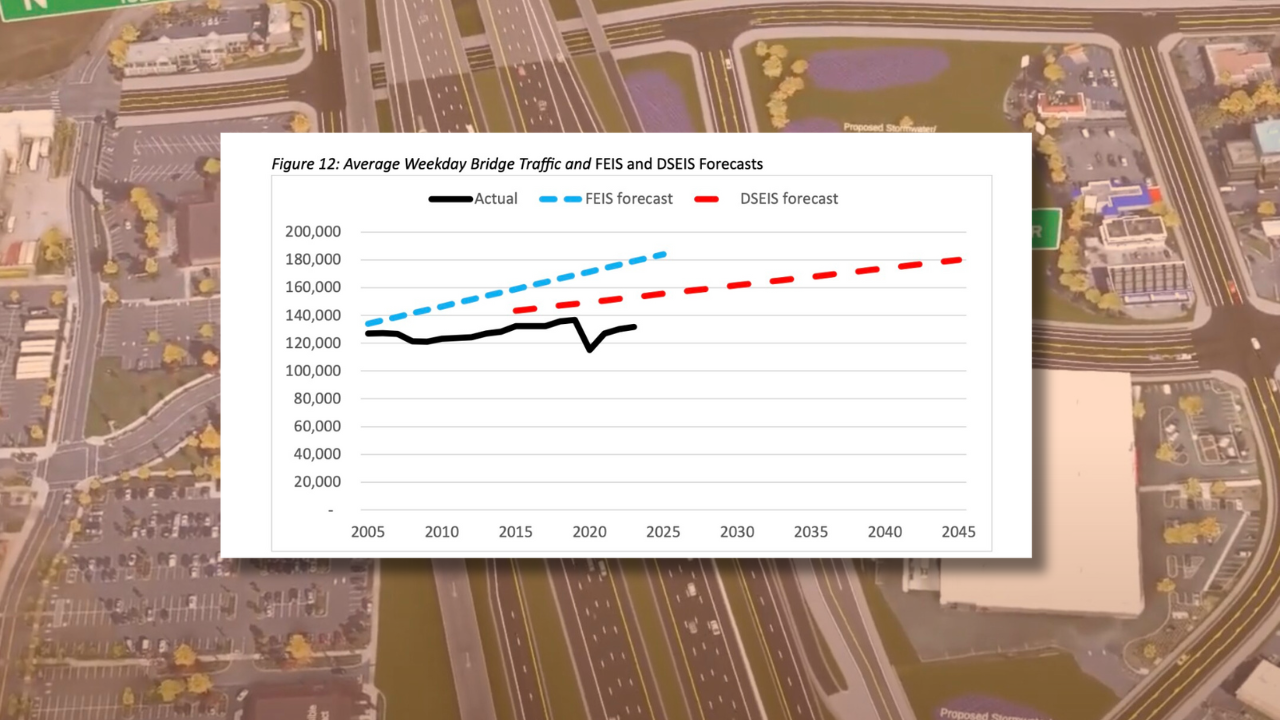

Marshall also claims that the IBRP SDEIS estimates for future traffic growth under the “no-build scenario” are “preposterous” and that there has been no growth in peak hour traffic on this section of I-5 since 2005.

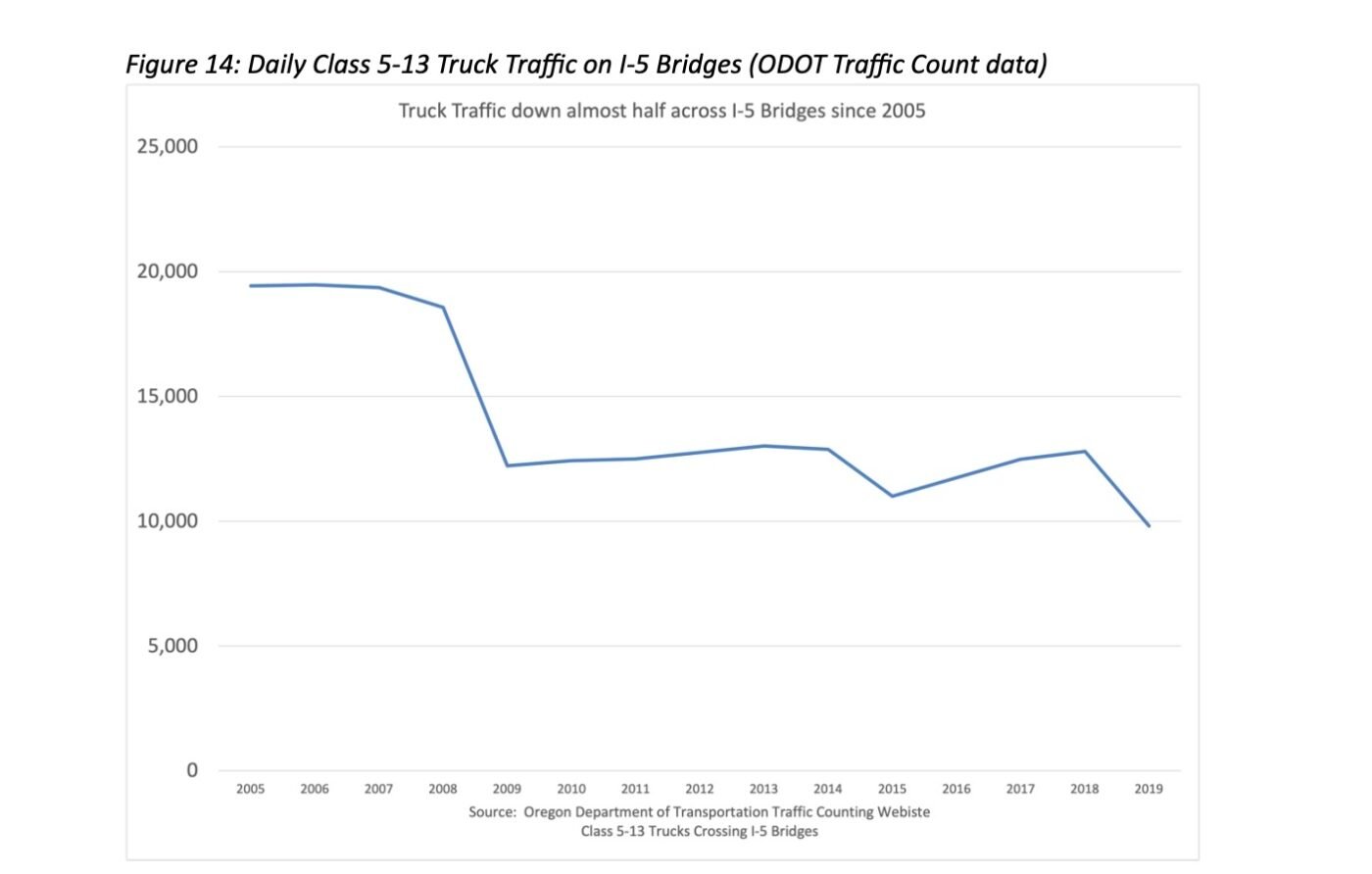

But how can governments justify a $7.5 billion investment without traffic growth numbers to back it up? Economist and freeway expansion skeptic Joe Cortright says the IBRP team “cooked the books” and simply adjusted numbers from Metro’s model to suit their needs. Here’s an excerpt from an article he published this week in City Observatory that claims project leaders (with the help of Metro’s model) “invented millions of phantom trucks to sell a wider bridge”:

“IBR and Metro inflated truck counts to exaggerate the current importance of trucks, and built traffic models that grossly overestimate the growth in truck freight. In essence, these flawed traffic models mean that IBR is widening a freeway to accommodate that truck traffic that doesn’t now exist, and based on false predictions of future truck traffic growth–when in reality truck traffic has been declining.”

Without traffic numbers they can trust, many advocates are scrambling to share impactful feedback during the SDEIS public comment period.

“The air quality and health impacts of this project are directly related to the level of traffic. We need accurate data to confidently assess these impacts,” said Neighbors for Clean Air Co-Director Nakisha Nathan.

Chris Smith echoed that frustration in our conversation earlier this week. “How is any organization like us — that’s trying to really understand the environmental impacts — how are we supposed to do that when there’s nothing in there [the DEIS] we can believe?”

“They tell a wonderful story,” Smith added. “That has no basis in any kind of rigorous analysis.”

— I’ve reached out to the IBRP and hope to share a response or follow-up on these issues soon.