What if you and your fellow Portlanders had a direct impact on what city funds were spent on? I’m not talking about lobbying politicians and then hoping they do what you want; I’m talking about true direct democracy where you come up with a project idea, work with your peers to flesh it out, get support for it from a vote of the people, then get it funded and implemented.

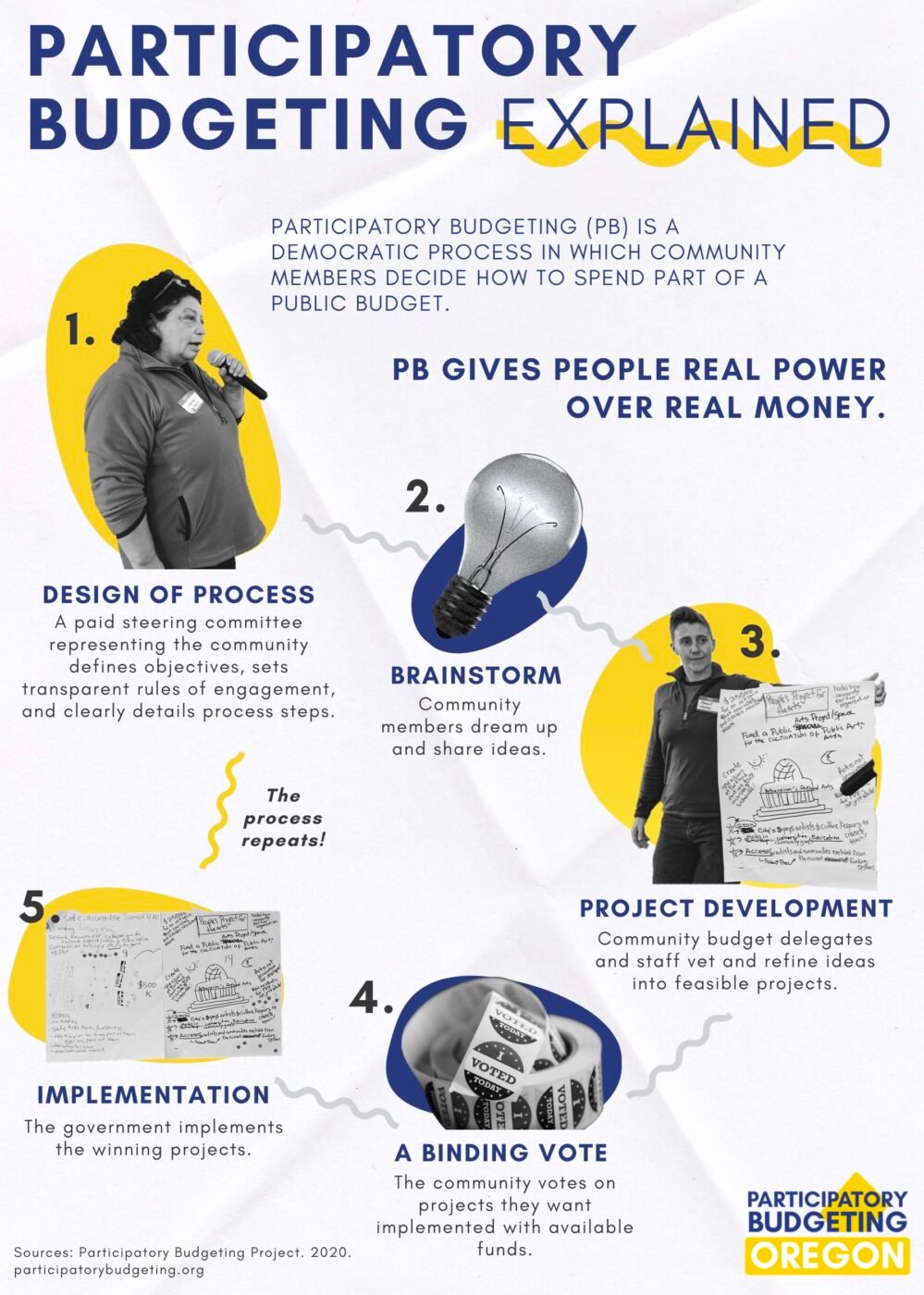

That’s the promise of participatory budgeting (PB), and a local effort to have it become an official part of the city of Portland’s budget process launched on Thursday.

The Community Budgeting for All campaign is gathering signatures to get PB on the ballot in November. The effort is being led by nonprofits Next Up, East County Rising, and Participatory Budgeting Oregon and their campaign wants to put at least 2% of the city’s General Fund budget — an estimated $15.6 million — into the hands of the people. Yesterday I interviewed one of PB Oregon’s staffers, Maria Sipin, to learn more about the initiative and how PB is different than the way we currently do things. (Watch our conversation below.)

As a former transportation planner with the Oregon Department of Transportation, Sipin saw first-hand that what gets funded often doesn’t reflect what people on the ground actually want and need. “What I personally like about it is in a PB process, you don’t end up with highway projects… people put forward projects in this process that have never been funded in the past, but should have. It addresses community safety, basic needs and all kinds of things that might have been overlooked.”

Don’t people already influence budgets by voting for elected officials and taking part in the budget process?

“Electing people is a form of democracy, but it’s not direct democracy. We can ask our elected officials to take action, but it doesn’t really require them to do something within a given amount of time,” Sipin answered. “It’s the legally binding aspect of PB that really can demonstrate people’s power and government’s ability to implement something that the people want.”

Asked for a specific example of a project like that, Sipin described school streets.

“[A type of project] that comes up a whole lot in spaces I’m in is keeping cars from approaching the school at a close distance and being able to save local streets for walking and biking safely and not dealing with the commotion of drop-offs and pick-ups of SUVs confronting their children at forehead height,” Sipin said. “If there was an appetite to create that type of street environment and PBOT said it could be feasible, you would work with PBOT, community orgs, parents, schools — to design a proposal.”

One thing I learned from talking with Sipin is that a big element of PB is community empowerment — not just in the form of controlling funds, but giving people the knowledge and experience about what things cost and how to develop high-quality funding proposals. I’ve found through doing BikePortland all these years that once you inform and empower people, amazing things can happen. And it’s a two-way street: regular folks like you and I would be engaged at a deeper level and city staff would learn what we want in an unfiltered way. But unlike a typical budget process where city staff and elected officials hold all the power, in PB, the scale of power tilts toward the people.

Below is a description of the process taken from the campaign website at CommunityBudgetingforAll.com, followed by the initiative language filed with the city auditor’s office:

Instead of typical backroom deals and ignored public testimony, residents would collaborate in the community and with City staff to develop and fund solutions. Portlanders would have a recurring avenue to bring forward problems, build skills, and relationships, and craft shared goals and solutions in partnership with City staff.

If it sounds like there’d be too many cooks in the kitchen, Sipin said a key part of a good PB process is one where the structure of decision-making is clearly laid out at the start. Professional facilitators are brought in to make sure things run smoothly, and a committee of delegates and city staff vet projects to make sure they’re feasible.

Another interesting wrinkle is that all Portlanders would be eligible to vote on projects — not just eligible voters. That means about 200,000 Portlanders — who aren’t currently on voting rolls — could have a say in how funds are spent.

Sipin says once people learn and participate in the process, PB becomes a tool that builds real community power. “PB is meant to be consistent and not a one time thing. Being able to witness this and be part of it, it’s really powerful,” she said. “And this is why some cities, once they put PB into place, it just becomes part of their democracy from here on out.”

Portland would become one of the last major west coast cities to institute a PB process, as the idea has caught on in many other cities around the U.S. and the globe (a portion of the European Union budget is allocated using PB principles). If this campaign can gather about 41,000 signatures by July and if voters support the ballot measure in November, the program would begin in the 2026-2027 fiscal year and the process would begin no later than July 2027.

— Learn more at CommunityBudgetingForAll.com.

View a short highlight reel of my conversation with Sipin below: