Readers might remember a couple of posts BikePortland published about a year and a half ago about a hapless ADA ramp in Portland Heights which had to be built four times (and torn out three) before it was finally able to pass inspection.

Well, it turns out that a neighborhood curmudgeon reported the fiasco to the city auditor’s Fraud Hotline. The auditor investigated, and indeed found that several ADA ramp installations were “inefficient and wasteful.” The auditor’s report came out a couple of weeks ago.

I’d like to revisit that episode, not just because the city auditor backed up BikePortland reporting, and not because KOIN’s Brandon Thompson put me on TV (and gave a shoutout to BikePortland reporting in his written article). That was all nice.

No, what’s really important about the saga is what it says about how our city government is currently organized, and what the city reorganization ushered in by charter reform is hoping to fix. Namely, the City of Portland employs a lot of hard-working, conscientious people who struggle to work within a dysfunctional organizational structure.

I can think of no better example of the resulting inefficiencies than this ramp imbroglio.

This is going to be another of my wonky dives into the details of how the city is run, but I’m someone who wants to understand why things are the way they are, and I think there is some light at the end of this tunnel.

The recap

As part of the Bureau of Environmental Services (BES) Goose Hollow Sewer Repair Project, the city was required to upgrade affected streets with ADA ramps. As the auditor’s report describes, BES was responsible for the overall project, with the Portland Bureau of Transportation (PBOT) providing “design, inspection, and other services” concerning the ramps. BES hired a contractor, and sub-contractor, to do the ramp construction. What could possibly go wrong?

The auditor’s report

Here’s a bit from the auditor’s report:

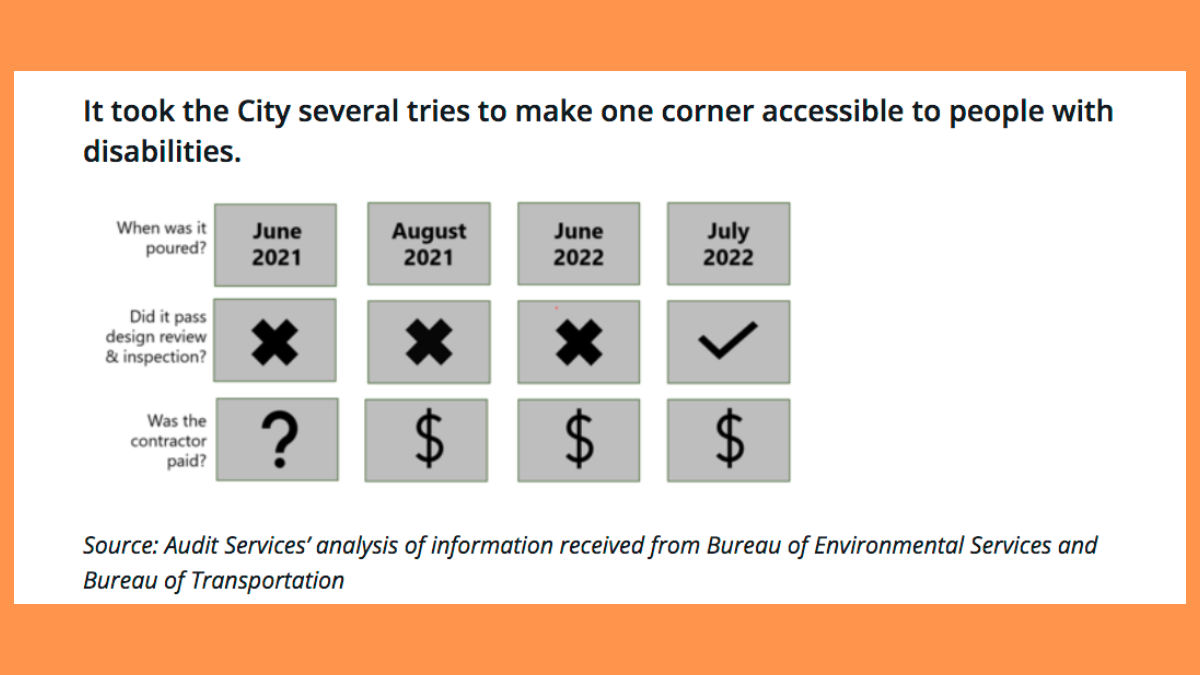

In October 2021, Transportation determined the contractor did not follow the design, but Environmental Service paid the contractor anyway because they later determined that even if the curbs had been installed as the plan directed them to do, they would not have met Americans with Disability Act requirements. Better coordination with Transportation could have prevented concrete being poured using a non-compliant plan.

According to photos from a local newsletter, an earlier concrete pour took place in June 2021, and those ramps were removed in July 2021. The Environmental Services work log did not cover that period of time because the contract manager for the project changed.

After several months of inactivity, and two more designs, Transportation determined curb ramps installed in June 2022 were also not poured per design. Environmental Services said that the contractor tried to make field adjustments and design revisions in collaboration with Transportation, but the ramps still did not pass inspection for Americans with Disability Act requirements.

The final curb installation we received records for was in July 2022, and Transportation determined those curb ramps were installed correctly in August 2022.

Basically, the report describes what we used to refer to as “spaghetti code,” a tangle of missed communications and unclear responsibilities.

The audit is a very readable five-pages long, and concludes, “when bureaus do not adhere to what they say is standard practice, they should do so with greater transparency, so that their reasons for not doing so are clear to policy makers and the public.”

The BES response to the auditor’s report is detailed and worth reading. Regarding a recommendation for “closer oversight,” BES replied,

Environmental Services agrees with this recommendation and is working on process improvements with PBOT as there are projects in process with ADA ramps. As curb ramps are a PBOT asset, PBOT staff are better equipped and trained to oversee the design, construction, inspection, and acceptance of curb ramps and determine their ADA compliance. BES is actively engaging and coordinating with PBOT to develop improved processes for design, construction, and inspection of ADA ramps on BES projects. When finalized, these improved processes will be implemented for ADA ramps on BES construction projects in the future.

Interestingly, KOIN reported that KC Jones with the auditors office told them, “during the transition, we’ve flagged this for the transition team as the sort of relationship that the city needs to kind of get better at.”

City reorganization

KC Jones’s “transition” refers to the reorganization of city government away from our current “commission” system, in which each member of the city council has a portfolio of bureaus to lead, to a more standard model in which the mayor heads the executive branch and implements city policy with the help of a city manager.

Two weeks ago, the City Council voted in favor of the new organizational chart. The nearly five-hour meeting began with a presentation by Shoshanah Oppenheim, the Strategic Projects and Opportunities Team Manager, the City Organization project manager Becky Tillson and Chief Administrative Officer Michael Jordan.

Jordan, who was for many years the head of BES, concisely summed up the pitfalls of the commissioner system. His comments were a spot-on description of what went wrong with the ADA ramps. Here is what he said:

I think we are all subject to thinking about organizational structure in a vertical way. Certain groups report to certain bureaus which report to certain executives which report to the mayor, ultimately. And we think about the organization in a very vertical way.

I think this reconstruction of the way we think about ourselves offers us an opportunity to look horizontally, across the organization. And to think about the city as a complete enterprise and how we allocate our human resources, how we think about the delivery of services, particularly within the city, to support the direct service delivery of our bureaus.

It provides us with that opportunity which we, quite frankly, lack today. It is very challenging for us to think horizontally across the organization. And I think this new structure gives us the opportunity, not only to think horizontally, but also to give clarity of accountability, and transparency about how we do business and what decisions get made, and where they get made in the organization.

The wastefulness of the ADA ramps installation is a perfect example of how challenging it is for the city “to think horizontally across the organization.” Imagine how challenging it is being the neighbor watching this unfold and trying to figure out who in the city to call.

Jordan knows the problems as someone who was running a bureau. He gets it.

I know the problems as someone involved in my neighborhood. When a neighbor can’t figure out who to call, they call their neighborhood association. This kind of between-bureaus problem happens often enough, I call it inter-bureau, interstitial purgatory—that sad space you find yourself in, caught between bureaus, acting as a human conduit for silos which don’t have one another’s phone numbers.

It’s one of the reasons I voted for charter reform, and I’m cautiously optimistic that soon our city will be running more efficiently.