A state lawmaker who represents Bend says her proposed electric bike legislation will be called “Trenton’s Law” to memorialize the tragic death of 15-year-old Trenton Burger. Burger was killed in a collision with a van after its driver made a right turn as Burger biked on a sidewalk along Highway 20 back in June.

Representative Emerson Levy presented her ideas at a meeting of the Senate Interim Committee on Judiciary in Salem last week. Since we reported on Levy’s efforts back in August, she has dropped the provision that would have made helmets mandatory for all e-bike riders (regardless of age).

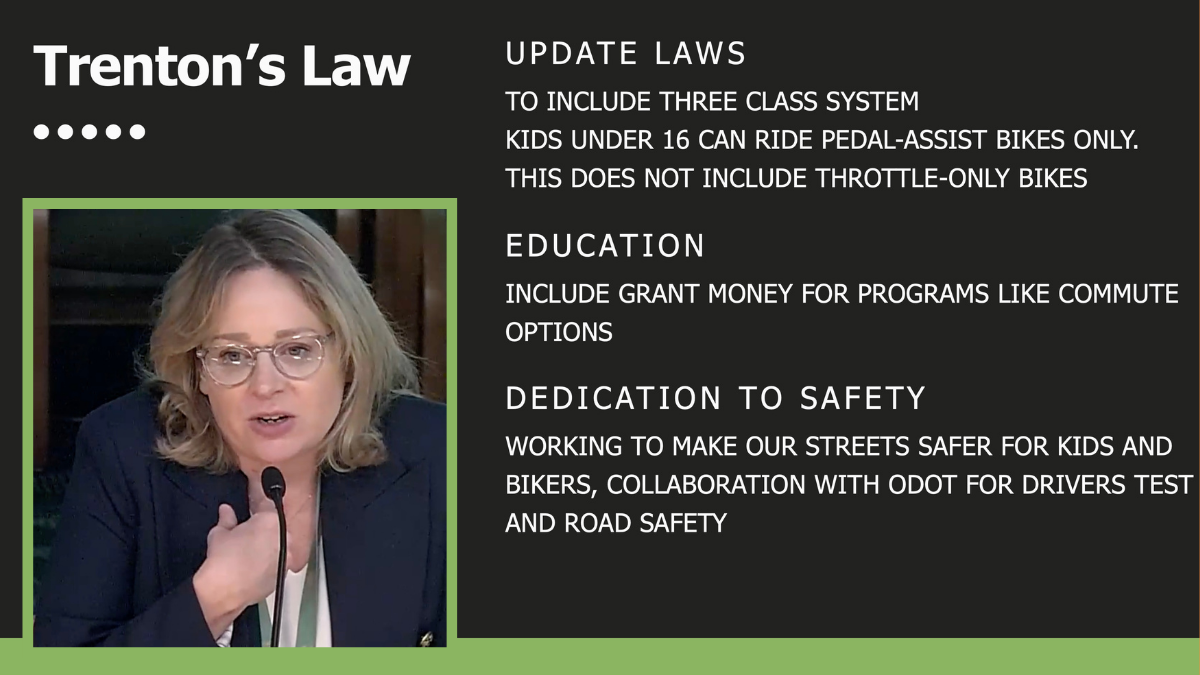

As presented on Wednesday (11/8) Levy’s proposal would:

- update Oregon to the three-class definition system that was recently adopted by the Biden Administration as part of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA). Oregon is one of 13 states that don’t use the Class 1 (20 mph with no throttle), Class 2 (20 mph with throttle), and Class 3 (28 mph max without throttle) system to regulate e-bikes;

- make e-bikes with throttles illegal for ages 15 and under;

- include grant money for bike safety education programs.

During her presentation to members of the Judiciary Committee, Rep. Levy implored them to not dismiss this as a niche issue that only impacts affluent people. “It’s an incredible safety problem,” she said. And right now it impacts four cities in particular — Hood River, Bend, West Linn, and Lake Oswego — but Levy believes they could be canaries in a coal mine as the market for the bikes matures elsewhere.

And if safety issues don’t persuade lawmakers to prioritize the issue in this short, interim legislative session (Oregon only has full sessions on odd years), the political saliency should. “I get more emails about e-bikes than homelessness, measure 110, housing — there’s no comparison,” Levy said. “And they’re all organic emails, several pages long. This is an issue.”

To make her case, Levy painted a picture that e-bikes with throttles are very easy to modify and can be made to go 45 mph just by connecting a few wires. She was also careful to not vilify this popular new mode of transportation:

“The fundamental value is that I do think kids should be out riding bikes, they should have the freedom. These are incredible tools, they’re incredible anti-poverty tools. But the line for me, and I think for the community, and all the testimony we receive is that we don’t need 13-year-olds on things that are functionally de-facto motorcycles. And so this is the compromise.”

Levy hopes her legislation will allow educators to go into schools to teach e-bike safety. That can’t happen now because it’s technically illegal for most students to even ride e-bikes — but that doesn’t stop them from being very popular.

Levy’s focus on making throttle use illegal is different than several other states that have opted instead to prohibit young riders from riding Class 3 e-bikes that can go up to 28 mph. This approach runs the risk of singling out throttles as being inherently problematic. Oregon Senator and Judiciary Committee Chair Floyd Prozanski responded to Levy’s presentation with a comment that’s indicative of this perspective: “I personally think full throttle bikes should not be in the bike lane,” he shared. “I think that they are basically modified little motorcycles and they should be in the lane that is equipped for that.”

Prozanski and several other Judiciary Committee members seemed grateful and very supportive of Levy’s work thus far.

Oregon’s E-Bikes for All Working Group met the day after Levy made her pitch in Salem. There was relief among some members that the mandatory helmet provision was dropped and one person noted that the possibility of requiring licenses and registration was a political non-starter inside the Capitol. There was also some concern expressed that Levy might add provisions to limit the potential of e-bikes in the future. She mentioned in her presentation she felt the 1,000 watt maximum power mentioned in the current law was “outdated.” That spurred one member of the group who represents a company that uses electric trikes to deliver cargo, to say 1,000-watt motors are essential to their business and their entire fleet would be illegal if a 750-watt max was enforced.

E-bike advocates in the working group also expressed an ongoing concern that lawmakers might be too influenced by anecdotal evidence and hard data needs to be a larger part of the conversation. And several members of the group expressed that the real safety hazards on our roads come from cars and trucks, and e-bike deaths and injuries are “just kind of a rounding error” by comparison.

If you’re in the Bend area, there’s a panel discussion planned for November 16th on the future of e-bikes in Bend that will be moderated by a reporter from the Bend Bulletin.