How do you accurately gauge what type of bicycle infrastructure treatments work best? Crash data alone is far from robust enough to get a clear picture. Video evidence can be helpful, but it’s a pain to gather and it’s not easy to create the controlled environments necessary for scientific research when you rely on real-life traffic.

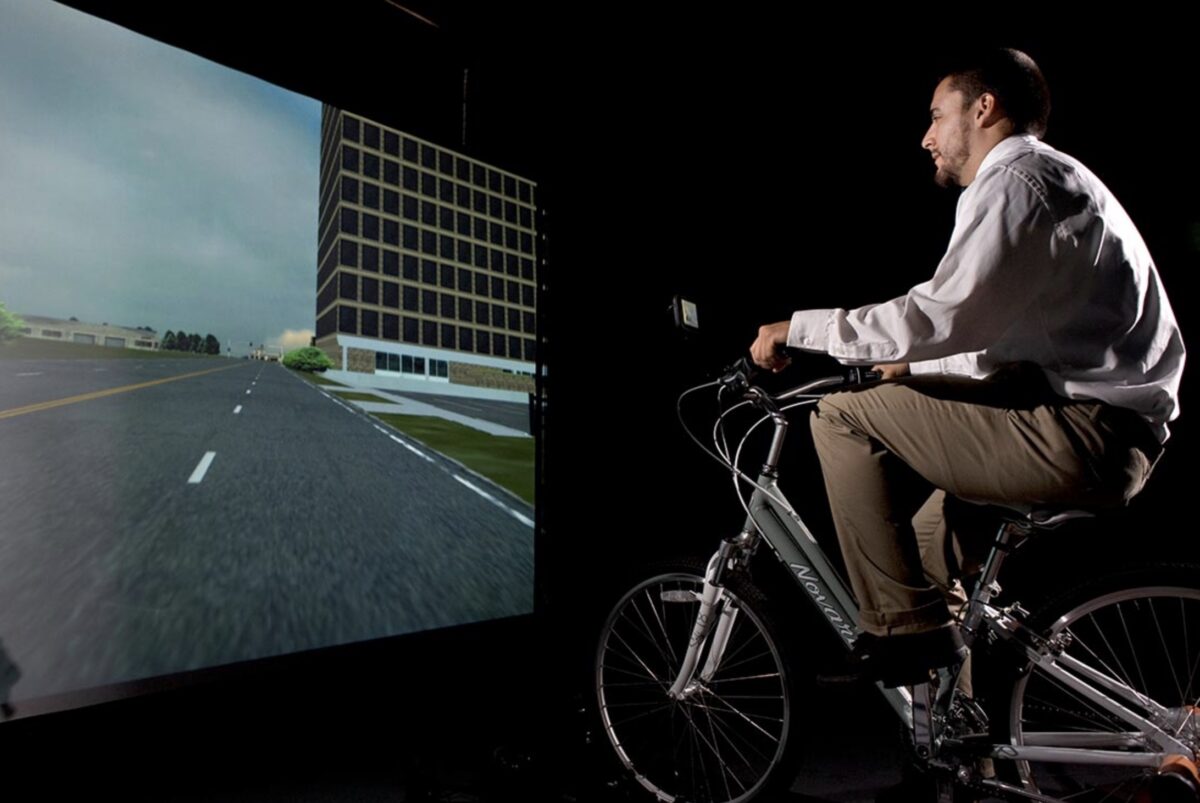

That’s where an innovative lab at Oregon State University in Corvallis comes in. Researchers there have a bicycle simulator that mimics traffic conditions (which you might recall from a story we shared back in 2011). And since it’s in a lab, riders can be tracked with all sorts of helpful technology to better understand how they react to different situations.

A new study by Logan Scott-Deeter, David Hurwitz, Brendan Russo, Edward Smaglik and Sirisha Kothuri published in Accident Analysis & Prevention (Elsevier, January 2023), used the simulator to compare three popular design treatments aimed at making bicycling safer. The research team (from Oregon State, Northern Arizona, and Portland State universities) wanted to know how riders responded when they approached a mixing zone, a bicycle signal, and a bike box. They tracked stress levels, eye movements, and riding behaviors of 40 study participants to see which design is best suited to avoid collisions.

If you ride in Portland, all three of these designs should be familiar to you. A mixing zone is where the bike lane drops just prior to an intersection and is replaced by sharrows and other lane markings. The idea is the markings will convey to bicycle riders they should expect drivers to “mix” with them as they cross over the lane to make a right turn. Bicycle signals have become relatively common in Portland in recent years. This is where a bicycle rider will have their very own signal phase to cross an intersection. And the bike box has been a standard treatment in Portland since 2008 or so. These are typically painted green and connect to bike lanes to form a large box at the very front of an intersection so bicycle riders can get ahead of drivers and become more visible.

To run the tests, the riders pedaled a stationary bike in front of large, panoramic screens and responded to 24 different traffic scenarios. To assess how each rider and design performed, researchers used a survey, tracked eye movements to quantify how long riders took to assess possible risks, measured stress levels, and marked down the path each rider took.

A majority of the riders identified as female and there was a wide mix of experience levels. 42% of them rode just one time per week or less.

The overall winner, when all factors where taken into consideration, was the bike box. Here are some key takeaways:

Mixing Zone

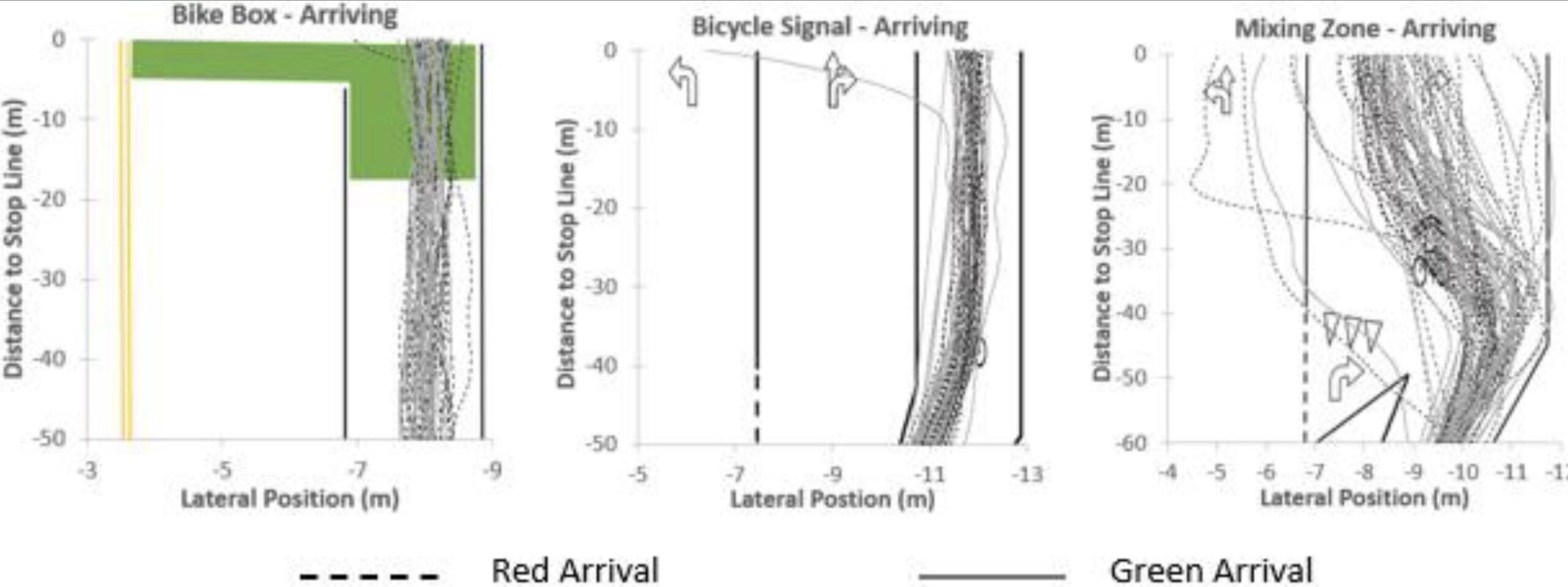

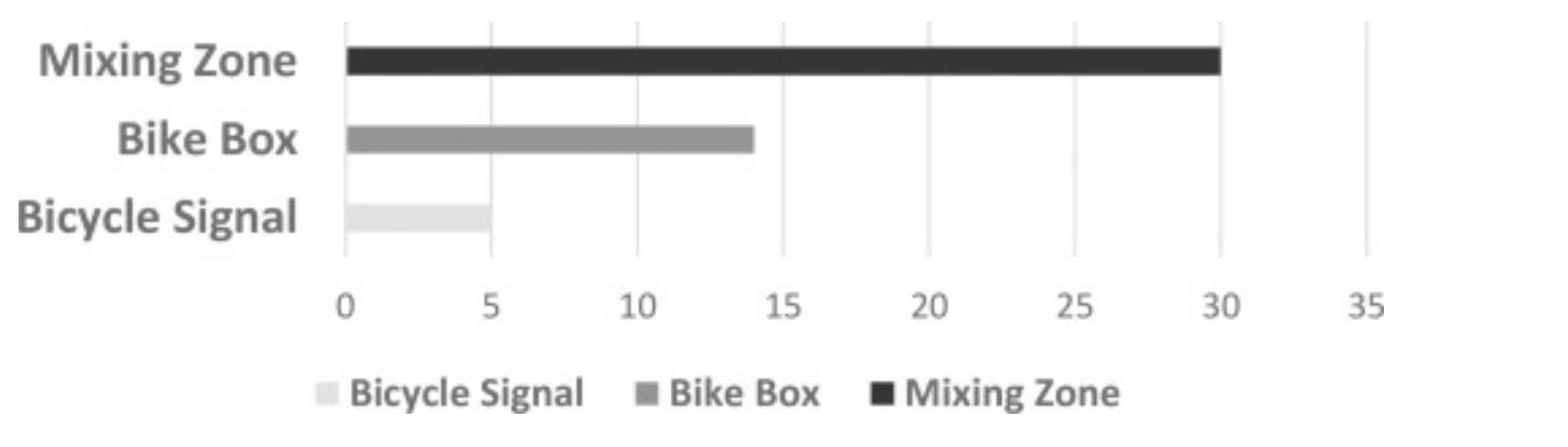

Not surprisingly, the mixing zone treatment “created the most discomfort” among study participants. It also led to the most unpredictable riding behaviors (see graphic). But there’s an important flipside to putting bicycle riders in a more stressful environment: they are more careful. Researchers found that, “The visual attention data of participants [in the mixing zone] indicated that they spent more time looking at the conflict vehicle… it supports [previous research] that a balance of user safety and convenience is an important aspect of creating safer facilities.”

Final verdict:

“The mixing zone may be best fit in scenarios where crashes tend to occur with a pre-existing bike lane, as the positioning data shows that bicyclists are willing to merge with the traffic and the provided right-of-way may allow safer movements between the two modes. The mixing zone treatment brought participants out of their comfort zone and required them to be alert of potential conflicts when claiming lane. Despite this effect, the sporadic and unpredictable riding habits associated with this treatment may expose bicyclists to higher risk scenarios.

Bicycle Signal

The bicycle signal made riders feel the most comfortable. This makes sense since it’s the only treatment that separates all users in time and space — as long as people follow the rules. But similar to the mixing zone, researchers noted an important caveat: Bicycle riders assumed the signals would do their job, so they rode with less caution and made fewer eye movements to make sure conditions were safe. Researchers wrote that, “This might increase crash risk with errant drivers.”

Verdict:

“Despite the high level of comfort associated with the bicycle signal as described in the survey results, there may be a treatment that performs better as the eye-tracking data revealed reduced searching for potential conflicts on approach. For this reason, we suggest bicycle signals be installed only when a clear need is present. “

Bike Box

Researchers liked the bike box most because it struck a middle ground of the pros and cons between the other two treatments. That is to say it offers a measurable amount of safety, while still giving the rider a sense that they should be ready to respond to potential threats.

Verdict:

“In scenarios where there is a large frequency of crashes, the bicycle signal may prove most effective as its design restrict conflicting vehicle movements with the bicyclists… Of the three intersection treatments assessed in this study, we recommend that bike boxes have proven to be the most effective treatment at promoting safe riding habits while also providing improved safety for bicyclists at signalized intersections.”

Do these findings jibe with your experience?

Read the full study here. And check out the simulator lab website here.