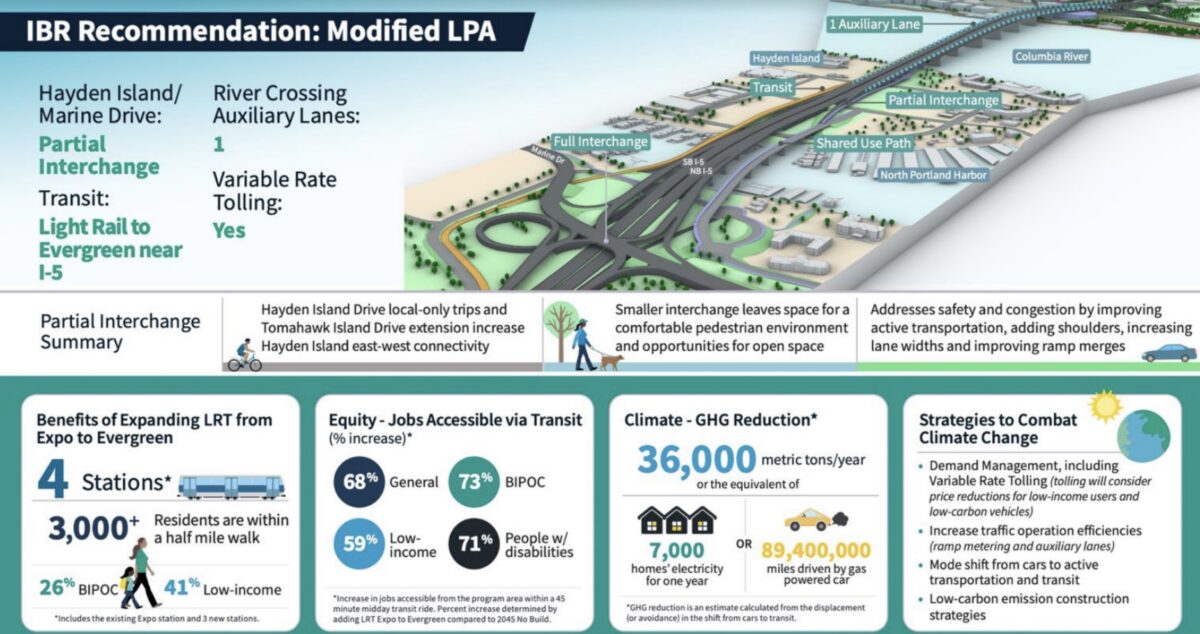

This week the Interstate Bridge Replacement announced they’ve selected a highway design that includes two “auxiliary lanes” that extend across the Columbia River alongside the three through lanes on I-5, leaving behind a design that included four auxiliary lanes that matched the design of the failed Columbia River Crossing project from 2013.

“The action you took today is closer to our objectives than the option you rejected, but we are not all the way there yet.”

— Chris Smith, Just Crossing Alliance

This slightly smaller footprint for I-5 definitely appears to be a concession to the voices pushing for the new highway to be “right sized”, but also stems from the project’s traffic models that show a minimal improvement in vehicle travel times for peak southbound traffic from an additional auxiliary lane. Rather than vehicle throughput, the IBR team has been framing the auxiliary lane as being primary for safety, to prevent rear-end collisions caused by merging drivers.

Commissioner Jo Ann Hardesty framed the choice as a win. “We wouldn’t have come this far if it wasn’t for the young climate activists and other community volunteers who have helped us hold this project accountable,” she said. But she was clear that she wasn’t endorsing all aspects of the project, but trying to maximize positive outcomes for Portland.

Advertisement

“Our job as a city has been to help the state make a project that does not undermine the City of Portland’s environmental and racial equity goals. Today we see a recommended alternative that is not perfect, and it’s not what we would have designed, and it likely could result in a marginal increase in automobile capacity,” Hardesty said. “We finally have before us a project recommendation that appears to be acceptable, with certain conditions that will help us make sure that the project delivers on its goals”.

Hardesty pointed to the increases in public transit service, reduced impact on Hayden Island, and investments in walking and biking infrastructure in northeast Portland as the biggest reasons Portland is signing off. She said that the pricing element of the project will help “restrain” emissions.

Metro Council President Lynn Peterson seemed even more eager to frame this as a big win, referencing the number of lanes that were planned on Hayden Island as part of the Columbia River Crossing. “17 lanes on Hayden Island down to three through lanes and a ramp-to-ramp configuration is significant progress and I want to take note of that,” she said.

But it’s important to note that the project is still incredibly early in design, and we haven’t seen renderings showing the true scale of the project, including what the partial interchange planned on Hayden Island will look like. We’ve seen with the Rose Quarter project how a project’s true footprint can be disguised until much further along in the process.

The IBR team is now touting a climate impact of 36,000 metric tons of GHG, or 89.4 million miles traveled by car per year. This number comes from an assumption that 4% of traffic on I-5 will use light rail instead. But the project team has already acknowledged that they don’t think the extension of the MAX Yellow line to the Vancouver library will be enough to meet demand for transit across the river. In addition, if travel times on I-5 improve thanks to those trips going to light rail, it’s likely that other drivers would simply fill that gap. The IBR’s “climate framework” doesn’t account for induced demand like this. We’ve asked some questions about these touted emissions gains but the IBR has told us it will take a week to get answers. For context, 36,000 tons is 0.08% of just the annual transportation emissions in Multnomah County.

Advertisement

Less happy with this announcement were state legislators, particularly on the Washington side. “This new project is actually worse than the old project,” Senator Ann Rivers said in a legislative committee meeting Friday. Senator Lynda Wilson concurred with Rivers. “We’re reducing this thing to practically what we have right now. It’s getting smaller and smaller, the footprint is getting smaller because we want less cars on the road…this isn’t going to get us there,” she said. Wilson wanted to know why the bridge was not being designed around autonomous vehicles. Wilson has been the most outspoken critic of light rail among the group of legislators who will buy off on the project.

Also not ready to jump on board is the newly-formed Just Crossing Alliance. Chris Smith, representing the group in public comment in front of the Executive Steering Group, said that “the action you took today is closer to our objectives than the option you rejected, but we are not all the way there yet.” Referencing the idea that transit demand couldn’t be fully met. “We want to leave no transit rider behind…we’d very much like to understand where those constraints are so we can help advocate to remove them and help maximize the transit potential of this project,” he said.

Other members of the coalition were more blunt. “The Columbia Bridge replacement is an opportunity to undo the past harm our transportation decisions have brought to underserved communities. Unfortunately, neither bridge alternative takes this opportunity seriously,” Paulo Nunes-Ueno of Front and Centered, a Washington coalition based around environmental justice, said Friday.

It’s likely that leaders like Lynn Peterson who are attempting to thread the needle on this megaproject will see criticism from both sides as evident that they’re heading in the right direction. A project design like this one was likely locked in many months ago when the decision to move forward with the 2013 Columbia River Crossing record of decision. But with so many more details left to be worked out, there are plenty of curve balls that could still get thrown toward this project.