Gas prices have shot past $4 a gallon and I’ve started to wonder if sticker shock at the pump will lead to less driving and more bike riding.

The last time gas prices spiked in Portland, we saw a big shift in bike traffic volumes (see chart at right). In late 2007-early 2008, the price of gas was a big deal. Experts said it happened for a mix of reasons including strong demand coupled with decreased production.

The result in Portland was a lot more cycling. It was even a cultural phenomenon. The owner of River City Bicycles, Dave Guettler, was so excited about the added cost of driving that he took out an ad in the local paper (below) to publicize a contest wherein they’d give away a free bike to the first person to guess the date when a gallon of gas would hit $4.00.

Two months after River City’s contest, gas in the Portland area hit an all-time that still stands: $4.28 a gallon.

As you can see in these photos, our streets became much healthier and more humane citywide as people hopped on bikes to save a few bucks.

Unfortunately for our city and planet, the high gas prices were very short-lived. A few months later gas was very cheap. On the bright side, we reported an optimistic view that many people would keep riding.

Today, due to Russia’s war on Ukraine, we see another gas price spike. According to AAA, gas has just ticked over the $4.00 per gallon mark in the Portland area. Coupled with the Covid-era bike boom, the red-hot climate crisis looming over us, and very uncertain global politics, one might expect another big rise in biking.

But for all the factors that might lead to more people biking in 2022, there are just as many reasons cycling rates will remain flat unless we change course. We cannot ignore how the underlying conditions that led to more biking in Portland in 2008 simply don’t exist today.

Portland was a vastly different place in 2008, especially when it comes to transportation.

According to U.S. Census data compiled by the City of Portland (in chart above), the overwhelming majority of new commuters added to our streets (the white line) between 2008 and 2018 hopped into a car (black line) while the number of bicycle riders (blue line) was relatively flat. During Portland’s cycling boom (from about 2000 to 2014), bike riders were able to absorb an impressive amount of new commuters overall. But in 2015 that black line (a fitting color to represent driving if there ever was one) ticked up.

The most popular narrative for why drivers and their cars took over inner Portland neighborhoods in the past seven years at the expense of other modes revolves around the cost of living. We had a dramatic rise in housing prices which forced a pedaling-friendly population further away from their jobs and destinations coupled with different behaviors of tens of thousands of new residents who moved here from places where cycling was only an afterthought. In other words, the people most likely to bike increasingly lived in places where it felt most unsafe and inconvenient to do so.

So what about the new residents who moved into those close-in areas with the best bike infrastructure? Places that had historically seen strong double-digit cycling rates?

If you look at just the numbers, Portland has added an impressive amount of bikeway miles to the network since 2008. A PBOT tally that combines mileage of neighborhood greenways, buffered/protected/painted lanes, and carfree paths, says we’ve added well over 120 miles of new bike infrastructure to our system in the past 14 years (and we hadn’t even started building protected bike lanes in 2008). Portland bike infrastructure has improved a lot since 2008.

But all the bike infrastructure in the world is meaningless if the number of cars overwhelms it.

Portland’s famous cycling neighborhoods in inner northeast and southeast built their reputation on shared roadways, what we used to call “bicycle boulevards” that are now known as neighborhood greenways. Because we failed to inspire new Portland commuters to hop on bikes and transit as our population and housing density skyrocketed, they filled up these once “low-stress, family-friendly” streets with their cars. This led to lots of cut-through traffic and related issues (like the bad driver behavior in the Tweet above and tightly-parked streets with terrible intersection visibility) that have discouraged cycling and initiated a negative feedback loop.

At a meeting of the Portland Bicycle Advisory Committee in February 2020, longtime PBOT Bicycle Coordinator Roger Geller said, “My thoughts are and my experience is that conditions for biking on these inner streets are deteriorating and that is having a deterrent effect.”

“As much as we complain about congestion, it’s still really easy to drive a car in this city,” he continued.

Not only is it too easy to drive, Geller said, but bike infrastructure that’s too reliant on backstreets is also too easy to miss from behind the wheel of a car.

“If there was a big, fat, green bike lane next them as they were driving with a lot of people biking on it, they might say, ‘Oh, I can see the way to bike. Instead of driving, I just get on my bike and bike these streets’,” Geller said.

Geller understands Portland’s bike network than any other human on the planet. In his mind, our network has simply been too shy. People who might like to meet it and start a more long-term relationship with it, are never even introduced.

Here’s more from Geller:

“The neighborhood greenway network is rather hidden, especially to people who are new to town. You have to know where this network is, you need a map to find it. If you live on Stark, you don’t know that three blocks north is Ankeny Street and that it’s a really great neighborhood greenway. So I think we suffer a little bit from the fact that the network is hidden.”

Even beyond the “hidden network” problem Geller identifies, much of the bike infrastructure we’ve built since 2008 is not good enough to entice a broad spectrum of Portlanders to use it. And even where the design is good, the lack of maintenance and connectivity means that far too much our bike infrastructure is safe and useful to only a small slice of hardcore riders.

But there’s reason for hope. The gas price spike of 2022 is just one reason why I think political and social conditions are ripe to turn our biking gloom into another biking boom.

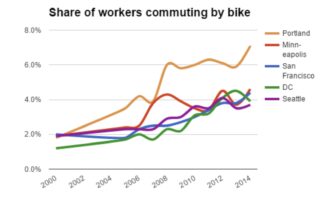

In 2013, just one year before we hit 7.2% — which was the highest cycling commute mode share ever recorded for a top 25 U.S. city — we looked back at what led to Portland’s bike boom and teased out five factors that led to it.

We wrote that cycling had succeeded in Portland because of the presence of five things: our “bike fun” culture (think Pedalpalooza and so on), excellent and inspired city staff, mature communication channels, committed activists, and a positive cycling feedback loop.

Do we still have those things? I think we score about 2.5 out of 5 on that scale, but I’ll save my rationale about that for a different day.

What do you think? Will high gas prices lead to more cycling? Would a boom even look the same given the big drop in commuters due to more working-from-home? What will it take for bicycling to make a comeback in Portland?