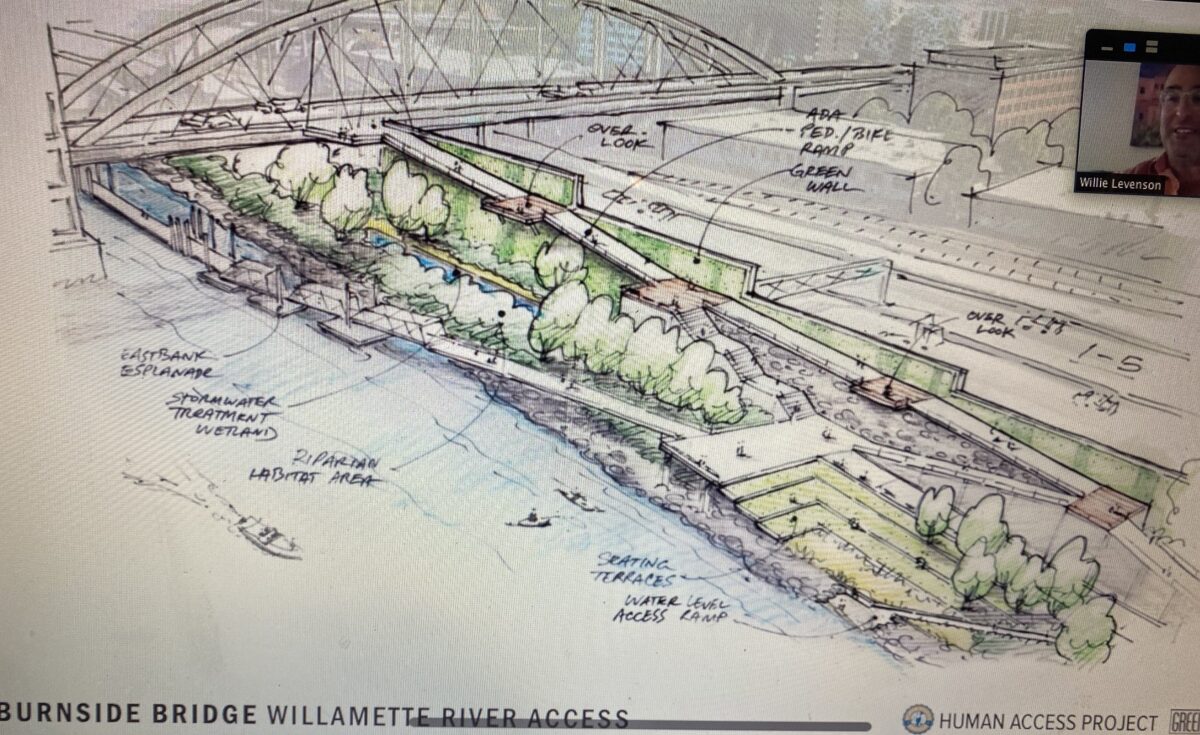

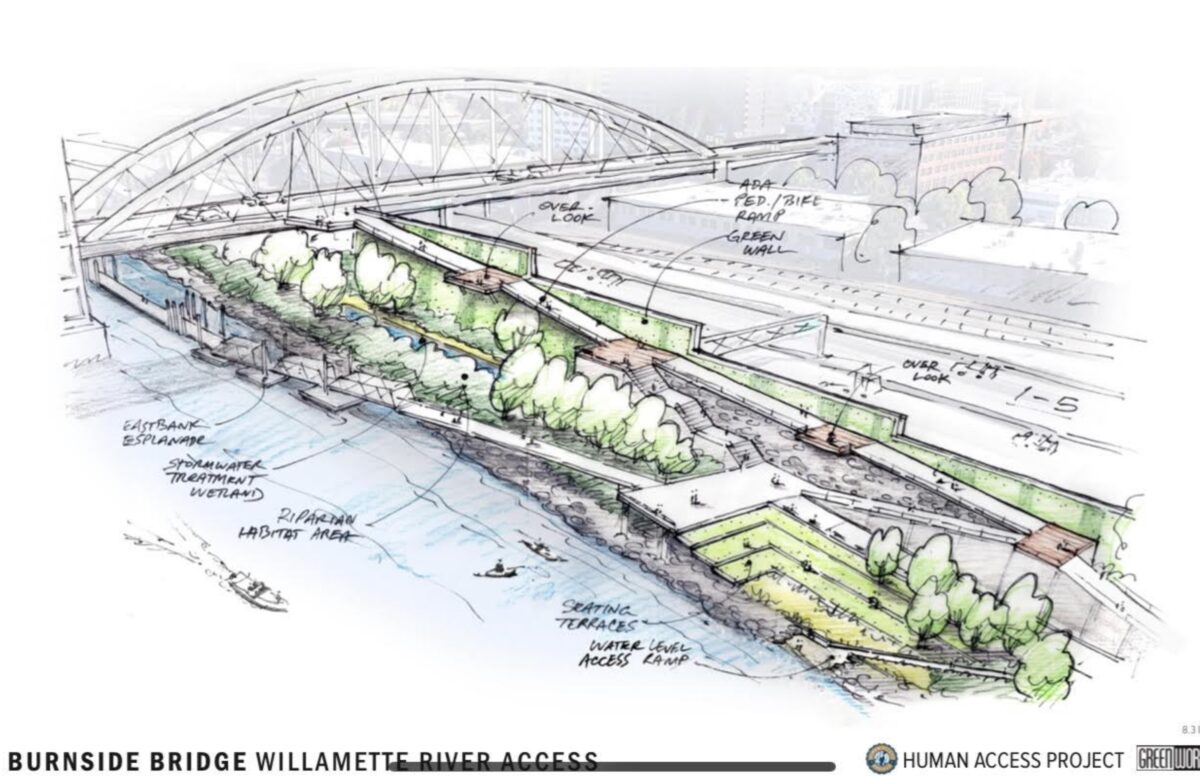

(Drawing by Greenworks)

If we ever get that dreaded Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake scientists predict, our beloved Eastbank Esplanade is very likely to fall into the Willamette River. But before you shed a tear, it’s also likely I-5 will drown too. I don’t want anyone to be hurt, but I find some solace in the fact that if/when the big quake happens, I’m confident we would rebuild the former and not the latter.

Those are just two tidbits I learned this week after attending two meetings about Multnomah County’s Earthquake Ready Burnside Bridge project.

Here’s a roundup of what else I learned:

Imagine a new beautiful park on the Esplanade

I know about the effort by the nonprofit Human Access Project to use the bridge replacement project as a trigger for building a great new park on the Esplanade, but hearing about it from the group’s founder Willie Levenson is on a whole other level. Willie joined the Bike Loud PDX meeting Monday night (via Zoom) to share an update on his latest project.

Calling for a new world-class green space, he called the Willamette River “Portland’s untapped blue space” and shared dreamy images of what we could create just north of the Burnside Bridge adjacent to I-5. An adroit activist, Levenson told the half-dozen Bike Loud volunteers huddled around a computer screen on the freezing patio of Lucky Lab pub in southeast that, “The very first step in getting a big thing done in any big public space is being told it’s absolutely impossible.” He said the current Esplanade is “value engineered” and Portlanders need to think bigger and support something that connects people directly to the water, while making sure it becomes a transportation corridor competitive with driving.

Speaking of which, the proximity of I-5 at this section of the Esplanade makes it a loud and stressful place (not to mention toxic). Levenson wants the Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT) to build a sound wall as part of the park project. Once that’s built, he said, “[The park will be] like the Chinese Garden in rugged Old Town, when you’re inside, you totally lose track that you’re even in Old Town.”

Central to Levenson’s vision is a new ramp from the Esplanade to the new Burnside Bridge. While the County has so far said an elevator and stairs is their preference, Levenson thinks support for a ramp is building and he won’t be surprised if the County changes position. “The county has said they’re building this bridge under an equity lens and it’s getting more and more difficult for them to stand behind an elevator knowing that it’s something the disability community is clearly against,” he shared in a conversation with me this morning. (More on the ramp versus elevator debate below.)

Bike Loud will meld Levenson’s vision into their testimony at Portland City Council this Thursday (12/16 at 2:00 pm) when the county and city will discuss an amendment to an agreement around staffing for the project.

Advertisement

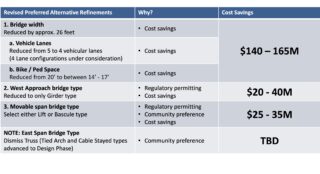

Why the project had a “change in funding context”

We’ve covered the budget crunch Multnomah County faces with this project. At a joint meeting of the Portland Bureau of Transportation (PBOT) bicycle and pedestrian advisory committees Wednesday night, I heard Steve Drahota, a planner with HDR Inc hired by the county, flesh it out a bit more.

“We’re here today because of this thing called a change in funding context,” Drahota said. Since the county believes the new bridge will be the only bridge in the downtown core that’s expected to be usable (based on their own criteria) after a major quake, they won’t cut corners on seismic resiliency aspects of the project. Hence their effort to chop the budget in other ways.

Drahota pointed to three causes of the $500-600 million funding gap: 1) The county relied on $150 million from the Metro funding measure that didn’t pass, 2) there is a lot of competition for grant funding from a variety of other projects and 3) inflation (in part due to Covid) that Drahota says have made some materials up to 300% more expensive.

Because of this funding gap, the county will take one additional year to complete a “Supplemental Draft Environmental Impact Statement” (SDEIS, part of the federal NEPA process). The current NEPA process will go through the end of 2022 and construction should start in 2025.

Ramps versus elevators

(Photo: Jonathan Maus/BikePortland)

We’ve covered this issue already, but I’ve learned a few new things this week.

— PBOT is actively involved in studying various ramp options (and that makes me assume they prefer the ramps over the elevators). Drahota shared a PBOT proposal at last night’s meeting that showed a design that connected to both sides of a new bridge. It makes sense for PBOT to work on the ramp designs, because it would fall into their jurisdiction. Drahota even posited that, “It could be that there’s a project that builds a world-class [ramp] facility led by the city in the future that connects to the bridge.”

The actual design of a ramp is still up in the air, but PBOT Project Manager Patrick Sweeney said a spiral ramp like the one on the Morrison bridge is “in the mix” of possibilities. The current spiral on the Morrison is, “Pretty steep and doesn’t meet ADA requirements,” Sweeney said, “But it’s very popular. and we’ve heard quite a bit from folks who really like that kind of design.”

— The county knows the public wants ramps not elevators. Drahota: “We’ve heard lately more and more desire for a ramp option, because it tends to always be there, and you don’t have some reliability questions that come with it.”

“The truth is I’m not so sure you’re going to have a functioning Esplanade when the earthquake is done.”

— Steve Drahota, HDR Inc.

— One reason the county considered elevators is cost. Their estimates says ramps would be twice as expensive as elevators — $15-20 million compared to $7-10 million respectively. And yes, that elevator cost includes expected maintenance. “Everyone acknowledges elevators are prone to lots of challenges; whether it’s a maintenance challenge or whether it’s a vandalism challenge,” Drahota said. “And frankly people just don’t want to use it because of what it means to be in a public elevator.”

— Asked by Bike Advisory Committee (BAC) Chair David Stein how an earthquake would impact elevator service, Drahota had a surprising answer: “The question is, will the Esplanade even survive the earthquake?” Drahota said the soft soils on the eastbank of the river are expected to liquefy in the quake. “The truth is I’m not so sure you’re going to have a functioning Esplanade when the earthquake is done. Most of our analysis is showing you won’t. The Esplanade will be fully displaced, and if you had anything in that space it’s going to go with it.” Why not beef up the soils? The county says the cost to un-liquefy the eastbank would be in the hundreds of millions of dollars. That begs the question: Since I-5 would be destroyed by the river too, we’d finally have a chance to reimagine the central eastside without that pesky freeway.

I asked Levenson with Human Access Project if he thinks the eventual destruction of the Esplanade makes his idea to spend millions on a new park and ramps less politically feasible. “Do we put our lives on hold and wait for cascadia to happen?” he replied. “Or do we take some baby steps to appreciate the river in its current form with the understanding that if we put something there and establish its use, we are more likely to get disaster funding to rebuild it.”

Advertisement

Ferry service during construction closure?

There will be a multi-year closure of the bridge while it is built. Someone asked whether the county had considered temporary ferry service to help folks across and Drahota said, “We’ve heard from the Frog Ferry folks and they are contemplating helping during that four to five years of construction… So who knows how that will play out.” I asked Frog Ferry President Susan Blandholm to confirm this and she said, “That would be news to us.”

What about the bike lanes on the bridge?

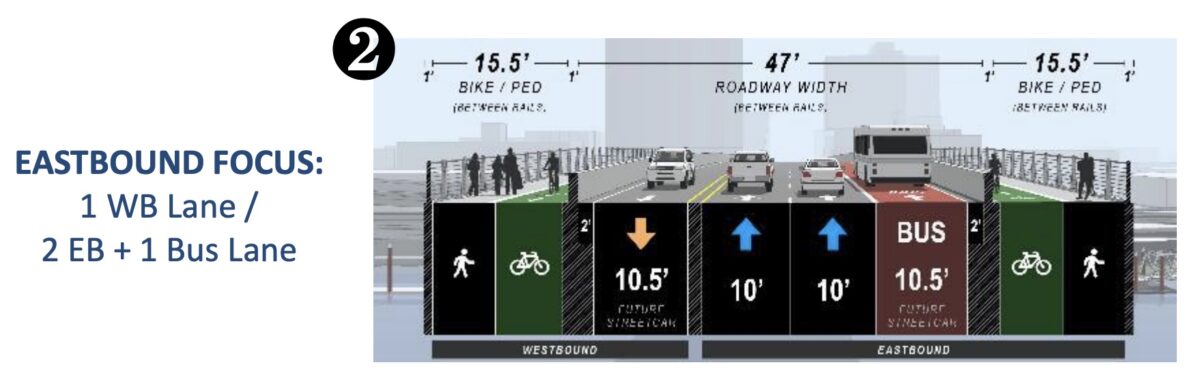

The cross-section will be narrower; but the actual lane configuration is still up for debate. Keep in mind as you read this section: The widths and usage of lanes will be a PBOT decision and won’t be set in stone until later in the design process.

The current bridge is about 79-feet wide over the river (the bridgeheads are wider). The county initially hoped to widen it to about 101-feet. Now to meet the cost crunch, they say the final width could be anywhere from 72-feet to 88-feet with their current preference falling somewhere in the middle of that.

All the configurations will include: an eastbound (away from downtown) bus lane, three general purpose lanes for car users, and protected space for biking and walking.

There seem to be two major options in play: the “eastbound focus” and the “reversible lane” (below).

Both could come with a 15.5-foot biking and walking path. The eastbound focus would have three eastbound lanes — one for bus (future streetcar) and two for driving. The reversible lane option would make one of the inside lanes eastbound or westbound depending on the time of day (it could be toward downtown for morning commute, away from downtown for the ride home). This type of configuration isn’t used anywhere in Oregon currently, so project staff are studying how it might work.

One drawback of the reversible lanes, HDR’s Drahota shared, is that the signage, possible gates, and other necessary infrastructure would add $1-2 million to the cost of the project, not to mention ongoing maintenance. Another big concern is how to merge that reversible lane back into the street network on either side of the bridge. BAC member Reza Farhoodi said, “I think the reversible lane option is just introducing a lot of operational complexity and potential safety conflicts that may not be necessary, given the traffic patterns on the bridge.”

“When I first got to the project that was one of the first things I thought: ‘Why are we not doing a two-way bike facility on one side?'”

— Sarah Daleo, PBOT

Also at last night’s meeting, BAC member Iain MacKenzie questioned project staff about the possibility of a two-way bike lane on the south side of the bridge that would connect them more directly to a future ramp down to the Esplanade. The county has considered a new signal to get bike riders from the north side, and any ramp design that has to cross under the bridge from south to north would add complexity and cost. So how about it Multnomah County? Drahota shot down MacKenzie’s idea, saying they’d already considered it but due to space constraints on either side of the bridge they didn’t think there was “any compelling reason to bring [the idea] back.”

PBOT Engineer Sarah Daleo said she initially liked the two-way bike lane idea, but had also scuttled it for the same reasons as Drahota. “When I first got to the project that was one of the first things I thought: ‘Why are we not doing a two-way bike facility on one side?'” Daleo recounted. But at each end with buildings abutting the bridge and with a one-way couplet at Burnside and Couch, it’s just a big mess trying to get it to work. It’s a great ide, it doesn’t pencil out.”

MacKenzie didn’t take no for an answer and asked if the “mess” and supposed lack of space for a two-way bike lane was due to a design that adds car turning lanes at the ends of the bridge. When Drahota confirmed that their proposal assumes car turn lane pockets at the ends, MacKenzie asked to see the detailed plan drawings. “I wonder, with a 110-foot cross section at the ends, if there’s a way to make that [two-way bike lane idea] work.” Drahota said MacKenzie could see the plan drawings when the SDEIS is complete, but MacKenzie wasn’t satisfied with that. “Is there any ability to have a look at that stuff before it’s all finalized?” he asked. “I’ll bring that up with the county,” Drahota said. Stay tuned.

MacKenzie’s questioning gets at a nagging issue for advocates who’ve been watching this project evolve. If we have an opportunity to build a new Burnside Bridge, doesn’t it make sense to make it as non-car oriented as possible right from the get-go? The Street Trust Director and BAC member Sarah Iannarone offered this take on the discussion just before the agenda moved on:

“I hate being forced into these cost saving discussions as if that’s the premise we have to accept, especially when we’re looking at the IIJA [Biden’s Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act] — bridges are one of The biggest pots of money… I know the pressure you’re under to widen these travel lanes for vehicles; but you really need to think about how we’ll be moving people across this bridge in the future. You hear the complaints of pedestrians who want to be free from people on bicycles and from people on e-mobility devices. We need to to maximize that space for those low-carbon modes. We can maximize the space for transit, we need to make sure freight has a clear pass-through, but SOVs [single-occupancy vehicles] are not our priority. It’s not in our Climate Action Plan, it’s not in any of our transportation plans, and it’s not in our shared vision for our community… I’m hoping the county will dig for money in other places… Let’s get creative and stay focused on building the bridge we want for our future.”