With talk in the news of reconnecting neighborhoods divided by freeways, and perhaps some federal money available to do it, I wanted to learn more about freeway capping.

I turned to Portland architect Rick Potestio. BikePortland readers probably know Rick as a co-founder of Cyclocross Crusade.

Potestio and I met recently for a free-wheeling lunch of big ideas on urban design, punctuated every twenty minutes or so by my pulling out a plan called “Bridge the Divide, Cap I-405,” and saying “what about this?” I wanted to keep the conversation grounded and learn what was possible, technically and financially, when folks say, “cap the freeway.”

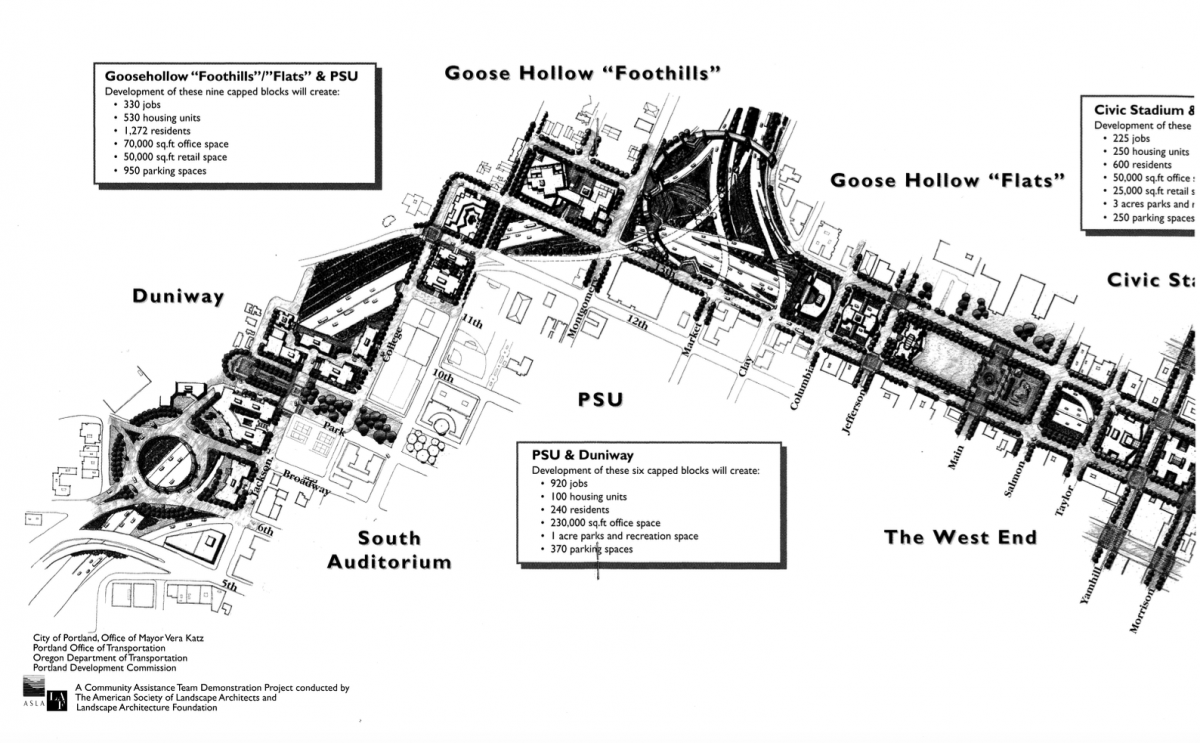

“Bridge the Divide” was a “Vision Study” solicited by then-mayor Vera Katz in 1998. The work was done pro bono by the American Society of Landscape Architects and the Landscape Architect Foundation on the occasion of their Annual Meeting and EXPO in Portland.

Katz really didn’t like I-405, ”Normally I would not advocate that we cover up our mistakes, but in this case I would make an exception.”

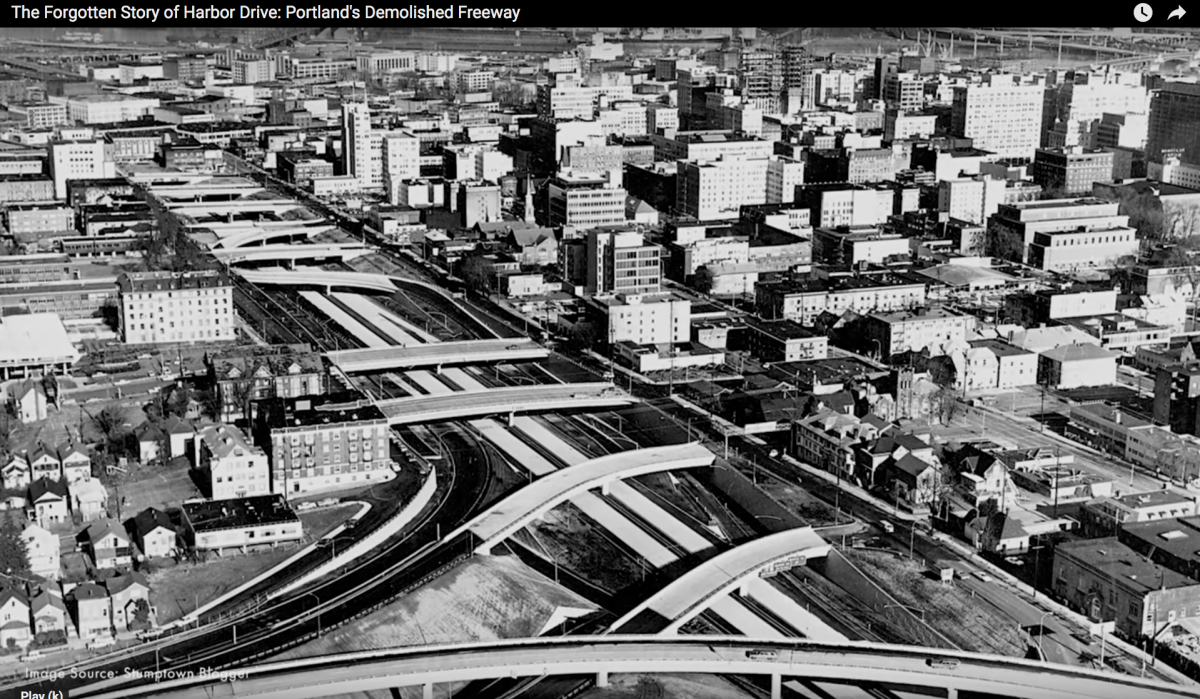

The I-405 and I-5 inner-city freeway loop was completed in 1973 with the opening of the Fremont Bridge. The loop divided downtown in half and separated southwest Portland from the rest of the city, with the working class immigrant neighborhoods of Lair Hill and Corbett bearing the brunt of the displacement. The southern end of I-405 also introduced a spate of seemingly intractable surface road problems that plague road-users to this day, including the freeway ramps on SW Broadway, 6th, 5th and 4th.

At its northeast end, the inner-city loop divided the Albina district, an historically Black neighborhood in north Portland. Currently, that segment is getting a lot of attention because ODOT wants to widen I-5 through that area with its I-5 Rose Quarter Project, but the Albina Vision Trust, backed by Oregon U.S. congressmen, want the freeway covered with buildable caps.

With the “Bridge the Divide” plan between us, Potestio and I started in.

Advertisement

________________________________________________________________________

BikePortland: Is this plan feasible? Engineering- and cost-wise?

Potestio: The problem with plans is that the people making them often don’t understand the economics of building them. If the economics of the plan isn’t achievable, it’s not going to happen.

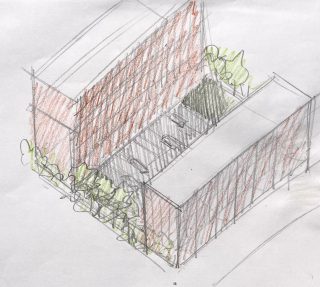

Here’s the way I think that freeways could be easily capped and affordably capped. Instead of trying to take a full block and decking over it, just span a reasonable dimension on either side of the streets, say 40 to 60 feet deep, about the depth of an apartment building. And you just basically build a a building that is a bridge—a big truss system—just the way we just built the Flanders bridge.

BikePortland: How high do you have to go to make this financially reasonable?

Potestio: I don’t know that you would have to go very high. I think you might want to go a minimum of six and maybe a maximum of twelve.

If you make the building small enough, and you’re just buying two to four trusses, in a way you’re avoiding buying foundations—you’ve got to build two bulkheads and use the trusses to span between the bulkheads.

So you’re economically ahead of the game because you’re not trying to build a deck that you’re then going to build on top of. The building itself is the spanning element.

“What you’re really after is connecting this side to this side in a way that you would walk across it and feel cool.”

It’s an integrated structural system that should pencil out, you could make it pencil further by giving the developer the air rights, and then you take it as high as you want. So in other words, instead of the developer needing to buy this piece of property, to the tune of tens of millions of dollars, you just give them the right to build there. And then you require that it’s a nice building that has openings on the street level.

BikePortland: Do you think it would be financially feasible to build subsidized housing over a freeway?

Postestio: Absolutely. No matter what you build in a normal circumstance, you have to buy the land and land costs are astronomical. So if you’re giving the person the land for free, you’ve offset the maybe quasi-additional expense of a more elaborate or more robust structural system to span that space.

But you’re going to need a structural system of some sort anyway. And a truss is a hyper-efficient structural system. If you can take the land costs away from the equation, I bet you make it look really attractive.

So now what’s the only hindrance? You need to get the federal government to allow you to do that.

BikePortland: According to the “Bridge the Divide” report, the city lost 38 blocks between Glisan and 4th when I-405 went in.

Potestio: Remember we basically preserved every 200 feet, those streets. If these buildings are flanking, maybe not every street, but maybe the major streets, Burnside, Yamhill, Morrison … With [the new pedestrian and cycle bridge at] Flanders, I would have added 10 or 20 more feet on either side of that, and let that be bike parking, bike services, food carts. That could have been anything in there. Once we put the expense of building that bridge, why wouldn’t we just go for a little bit of extra expense and make it a real amenity?

That’s how they used to do it in medieval times, that’s the Ponte Vecchio in Florence, where they added shops to each side of the bridge.

And again, I’m not saying deck the whole thing. That’s where I think everyone gets into trouble. Just line streets with truss buildings. This is far less expensive than putting a massive deck. And it gives you far more activity and utility at the street than a big empty deck with a park or some food cart pod or whatever. A deck–it’s not even a destination, you know you are on top of a freeway.

BikePortland: And that is not a problem with the buildings?

Potestio: If you’re walking on these streets, you’re not going to know that you’re crossing a freeway. The backside, because you’d have the sound and the exhaust and all that stuff, maybe this is more of a closed side. So you might have to really think what type of use is going here.

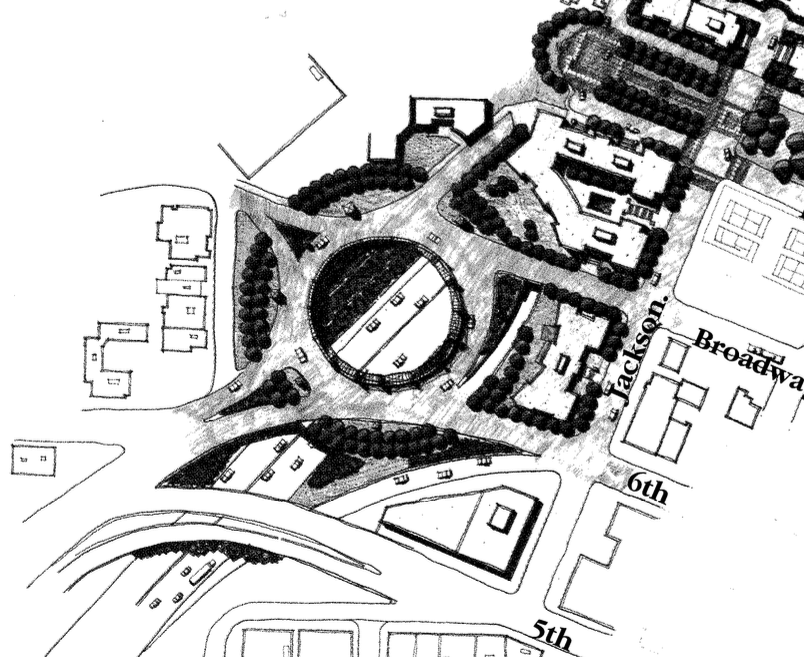

BikePortland: Let’s move to the south end of this plan—the connection between Duniway Park and PSU, and the extension of the south Park Blocks across the freeway. The area is a traffic quagmire—a collision between the vision the Olmsted brothers 1904 plan for a Portland park system, and Robert Moses’s downtown Portland freeway loop.

The Olmsted brothers had intended Terwilliger Blvd to connect through Duniway Park all the way to the South Park Blocks—one long north-south park running the length of west Portland. The connection was never built, and now the freeway chasm plows through where it would have been.

Is this roundabout buildable?

Potestio: Back to Olmsted and [architect Edward H.] Bennett and the early days of this city, we did have a clear vision for how it could come together with planning for architecture, development, parks and transportation. It was integrated and it was visionary and it would have been beautiful. We abandoned those plans, partly due to the economics and circumstances of the world, the depression, and two world wars. And then the pivot to cars being the primary mode of transportation.

To get to your roundabout question, I don’t know about this, because I’d have to look at this in the bigger context. But that concept I think is the way to do it.

I don’t know that that needs to be a circle like this with cars spinning, but maybe it’s just two of these coming across that allow for the connectivity of the surface of streets and pathways. So that it’s—what you’re really after isn’t a circle of cars whipping around, what you’re really after is connecting this side to this side in a way that you would walk across it and feel cool.

— Lisa Caballero, lisacaballero853@gmail.com

— Get our headlines delivered to your inbox.

— Support this independent community media outlet with a one-time contribution or monthly subscription.